Inside Mexico's feared Sinaloa drugs cartel

- Published

Some of Mexico's leading drugs traffickers have been killed or captured in recent months, including the head of the powerful Sinaloa cartel. But inside the secretive world of this feared criminal organisation it's clear that it remains as active as ever.

Hector is not what you might expect a drugs smuggler for the Sinaloa cartel to look like. There is no flashy truck and chrome-plated Kalashnikov. Instead, the spry 68-year-old drives a tiny Honda and runs a small convenience store.

But he is the real thing. I had asked a Mexican contact with knowledge of the cartel to introduce me to someone on the inside. For years, Hector has been his guide to the secret workings of the oldest and richest drugs mafia in Mexico.

The Sinaloa cartel - its tide of dirty cash and its pitiless violence - reaches into the police, business, and politics. The arrest in February of the cartel leader, El Chapo "Shorty" Guzman, made little difference to the organisation - there is too much money to be made.

"This place is sick with the narco culture," says my contact. "They have been living with it in Sinaloa for 100 years."

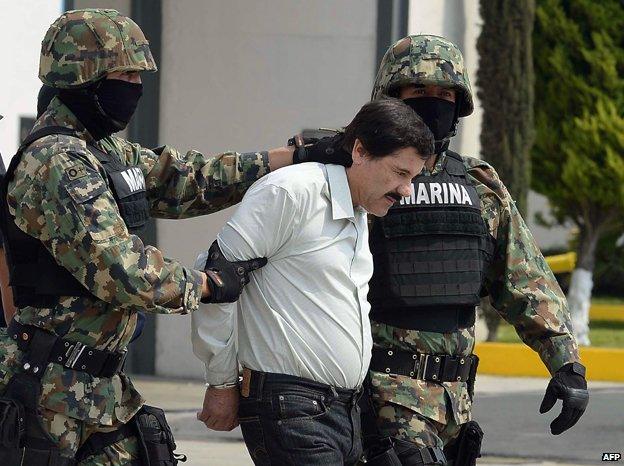

Joaquin Guzman Loera, aka El Chapo Guzman, is escorted by marines in Mexico City in February 2014

Hector has been a narcotrafficante for 50 years. "I am a pioneer," he tells me proudly, wearing a white cowboy hat, and swirling the ice around in a glass of whisky.

His father had been a poor farmer, planting corn and beans. In his teens, Hector grew marijuana, then began smuggling his crop to the US, where it fetched a much higher price.

He survived all this time by being smart, he told me. The shop, for instance, is his alibi.

"When I was young, I wanted to make lots of money. And for a time I did," he says. "But I live better now because I don't have to hide."

He has many regrets, including the loss of his son, killed while trafficking. "Truly, the business has changed," he says. "The people have changed. There is no respect. The nobility is gone. There is no friendship. There is no promise. Before, if you owed money, your word was good. Now you will be killed tomorrow if you don't pay today."

The blood flowed when, several years ago, the trafficking of crystal meth began to overtake that of the "noble" drugs marijuana and cocaine, he says. A pound of white, crystalline methamphetamine is bought from a lab in Mexico for $2,000. It is sold in the US for $10,000 - after smuggling costs you can clear $5,000 a pound. The obscene profits and the drug itself were corrupting, he explains.

"The person who uses crystal meth can hang his mother. The change to synthetic drugs changed the mentality," he says.

"When the meth boom started, the war started, the jealousy started. The different cartels started to recruit people who had never seen a Kalashnikov.

"They give them a rifle, they give them drugs and those people turn crazy, they don't think about tomorrow. People are sick - the ones who kill and the ones who send them to kill."

The drugs war is conducted by the sicarios or "blades" - cartel hitmen. They guard the shipments and the money, protect the cartel's turf from rivals, and kill to order.

We are taken to a safe house used as a base by one group of sicarios. The smell of marijuana is heavy in the air as we walk in. A dozen young men lounge on sofas watching TV.

They are well armed - many have AK-47s, known affectionately as "goats' horns" by the traffickers because of the curved clip for the bullets. One or two have M-16s with grenade launchers, weapons not even the police have.

I speak to Raphael, a dead-eyed 18-year-old with a Kalashnikov, a black combat vest stuffed with ammunition clips, and a pearl-handled revolver.

"A friend a mine told me about this business," he says. "He was part of this team. So I joined too. I was 14 years old. I was not good at school. I like this. How to explain? I don't like fighting but I do like the weapons."

He was 15 when he first killed. He saw an informer on the street and phoned for orders. "Kill him," he was told. So he did, there and then, shooting the man. "I felt nothing," he tells me. "Just adrenalin."

He has lost count of the number of lives he has taken since. No-one in the safe house has an exact number. At a guess, most think they have each killed a dozen people in the past year or 18 months.

The most recent "hit" was two weeks ago - someone from their own group accused of passing information to rival traffickers. The boss of the safe house, an innocuous looking 26-year-old in a striped polo shirt, garrotted him from behind with electrical cable.

The head of security for this branch of the cartel, a man in his 40s called Jose, says almost anyone can be a target. "A traitor, a whistleblower, a thief, someone who doesn't pay the cartel. They send us to collect the money or to kill him."

But he also claims that the cartel protects the people of Sinaloa. That is not as strange as it sounds. The Sinaloa mafia has, by and large, not carried out the kidnapping and extortion seen elsewhere in Mexico.

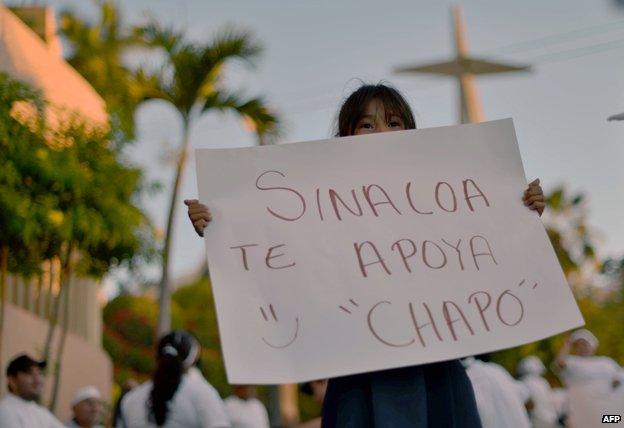

Girl holds up a sign reading: "Sinaloa supports you Chapo"

That would be bad for business, and the trafficking is far more lucrative than anything else they could do. The cartel has even killed and put on display the bodies of criminals accused of kidnapping for ransom.

"So the people protect us," says Jose. "Most people do business with the cartel or join it. It's almost an obligation here because if you don't you're on your own. You are against everyone else. There is no protection."

The firepower has not been produced for our camera, they assure us. They wait like this, ready to go to war at a moment's notice - there has been some trouble recently with rival cartels trying to edge into their territory.

Some in Mexico talk of a "narco-insurgency", a well-armed challenge to the state. In Sinaloa, that is not the case, it seems. "We work with the police," says Jose, "local, state and federal."

When his drugs are moved, it is with a police escort, he tells me. Officers keep an eye out for gunmen from rival cartels. "The police are co-operating to take care of the [smuggling] corridors. They are 'vigilantes' for us."

The state police chief Commandante Jesus Aguilar emphatically denies this. His men, in their blue combat uniforms, also bristle with weapons - M4-A4 assault rifles, 50-calibre sniper rifles, heavy machine guns mounted on the back of huge, gleaming new pick-up trucks.

Improved equipment and higher wages have helped them arrest many traffickers, Aguilar says - including, only a week ago, 10 Sinaloa gunmen.

Local police at the scene of a crime in Culiacan, Sinaloa

"We have arrested people from all sides," he says, in an office decorated with certificates, including one from the US Drug Enforcement Administration. "They are all criminals. We don't favour some and not the others. Here, everyone engaged in criminal activity can expect to be arrested by the authorities."

The commandante has had his own troubles with the authorities. In 2006, a warrant was issued for his arrest, after he was accused of using his men to protect one of the most senior members of the Sinaloa cartel.

He went on the run for five years and had a five million peso bounty on his head (the equivalent of $500,000). "It was a very small bounty," he says, laughing, and adding that the case against him was "political".

The warrant was withdrawn in 2009 and a couple of years later he was re-appointed to head the police. The state governor explained that sometimes a "black dove" was needed to take on organised crime.

A former governor of Sinaloa once said that 62% of the state's economy was connected to drugs money, but few in Sinaloa are prepared to speak publicly about the links that everyone assumes the cartel has with the authorities.

At the Sinaloa Commission for the Defence of Human Rights in the state capital, Culiacan, I meet a small group of women whose relatives have disappeared. They all accuse the police of failing to investigate the abductions properly because of links to the criminal groups.

One woman, Annabel, goes further, accusing the police of having a hand in abducting her son. He was drinking on the street with a few friends when four patrol cars drew up. They arrested her son and two of his friends.

At the local police station, the chief denied all knowledge of the arrest. Hours later, she got a call from a gang of kidnappers: "We have your son."

They briefly put her son on the phone. "I'll be OK if you pay," he pleaded. The ransom was $10,000 and the family car, which was to be left, with the money, in a square in town.

She did as she was told. The car and the money were taken. Her son was not returned. She never saw him again.

The police told her that "fake cops" were involved. She doesn't believe it. There were too many police cars.

"I begged the police - tell me where my son is and who has him," she recalls tearfully.

There are other stories. People are too terrified to show their faces on camera. No-one believed the authorities would really help them.

The traffickers have co-opted parts of the state. For Mexicans, that is the really frightening thing about living with the drugs business… You never know who you're dealing with, who to trust.

Several names, and other identifying details, have been changed in this piece.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external