How the UK taught Brazil's dictators interrogation techniques

- Published

As the world focuses on the World Cup, which opens in Brazil in less than a fortnight, many Brazilians are wrestling with painful discoveries about the military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1964 to 1985. The BBC has found evidence that the UK actively collaborated with the generals - and trained them in sophisticated interrogation techniques.

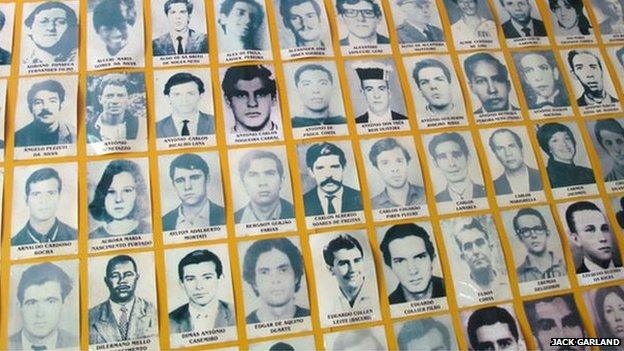

Brazil's 21-year dictatorship is less well known abroad than that of Argentina or Chile, but it was still brutal. Hundreds died and thousands were imprisoned and tortured.

One of those tortured was a left-wing guerrilla who is now the country's president, Dilma Rousseff. She set up a Truth Commission to unearth long-buried facts about the past.

As former victims and a few military players come forward to give evidence, Britain's secret role has emerged.

By the early 1970s Brazil's rulers were engaged in a bitter struggle against left-wing guerrillas. Swept up in the oppression were union leaders, students, journalists and almost anyone who voiced opposition.

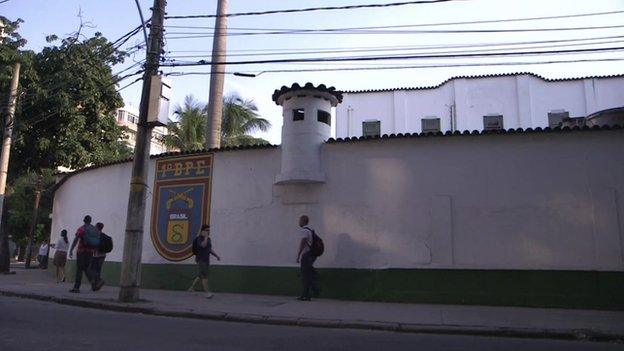

Alvaro Caldas belonged to a communist group when he was arrested in 1970. He was held inside the military police barracks in Rio for over two years.

He was subjected to severe beatings, electric shocks and the notorious "parrot's perch", which meant being tied to a horizontal pole and hung upside down for hours.

On his release he gave up politics and was working as a sports journalist when, in 1973, he was re-arrested. He was brought back to the same building, but inside it had been completely transformed.

"This time the cell was clean and sterile with a nauseating, sickly smell. The air conditioning was very cold. The light was on permanently so I had no idea whether it was day or night. There were alternating very loud and then very soft sounds… I couldn't sleep at all."

Alvaro says his overriding emotion was fear. Periodically he would be hooded and taken out for questioning. He felt the aim was to destabilise his personality so he would confess to something he had not done. This was not physical torture but instead intense psychological pressure.

"Luckily I was only there a week, if I had been there for two weeks or a month I would have gone mad," he says.

This new kind of interrogation method came to be called the "English System". Evidence from the Truth Commission explains why.

One of the most feared torturers, Col Paulo Malhaes, gave 20 hours of testimony. He arrived in a wheelchair looking frail. He then confessed to killing and mutilating his victims. He also expressed great admiration for psychological torture which, he felt, was more effective than brute force, especially when it came to turning a left-wing militant into an infiltrator.

"Those prisons with closed doors, you can modify the heat, the light, everything inside the prison, that idea came from England," he said.

He admitted, privately, to the prosecutor, that he himself had gone to England to learn interrogation techniques that didn't leave physical marks. The prosecutor, Nadine Borges, revealed her conversation with him.

"The best thing for him was psychological torture. When a person was in a secret place, it was faster to obtain information. He also studied in other places but he said England was the best place to learn."

Malhaes was murdered in a burglary at his home shortly after giving evidence.

Photographs showing some of the Brazilians who died and disappeared

Prof Glaucio Soares interviewed more than a dozen of Brazil's top generals back in the 1990s. Several of them told him they sent officers to Germany, France, Panama and the US to learn about interrogation but they praised the UK as having the best method.

"The Americans teach, but the English are the masters in teaching how to wrench confessions under pressure, by torture, in all ways. England is the model of democracy. They give courses for their friends," he was told by Gen Ivan de Souza Mendes - an interview recounted in the book Years of Lead which he co-authored with two other Brazilian academics.

Gen Aoyr Fiuza de Castro said the British recommend interrogating a prisoner when he was naked as it left him anguished and depressed, "a state favourable to the interrogator".

The UK was apparently seen as having effective practices as it had faced a serious insurgency in Malaya up until 1960 and had latterly honed its techniques in Northern Ireland.

The method, using sensory deprivation coupled with high stress, has come to be known as the "Five Techniques". These were:

standing against a wall for hours

hooding

subjection to noise

sleep deprivation

very little food and drink.

Many argue the techniques amounted to torture and they were officially banned by Prime Minister Edward Heath in 1972, after a furore over their use on IRA internees.

But in Brazil, these psychological interrogation methods fulfilled the military's need. The regime's dismal human rights record was beginning to attract adverse publicity around the world and the old physical forms of torture were killing too many victims. A method that would leave no marks and was still effective to extract information from prisoners was exactly what the generals wanted. They could combine these techniques with knowledge gleaned elsewhere.

Apparently, not only did army officers go on courses in the UK, but British agents went to Brazil to teach. A former policeman, Claudio Guerra, says they gave courses inside Rio's military police headquarters in how to follow people, how to tap phones and how to use the new isolation cell. He saw these agents when he came to collect the bodies of those who had been tortured to death by interrogators using the old system of physical pressure.

Emily Buchanan's film for Newsnight details evidence showing how British agents taught psychological interrogation techniques to officers working for Brazil's regime in the 1970s.

None of the military or police involved in the old regime has yet been brought to trial.

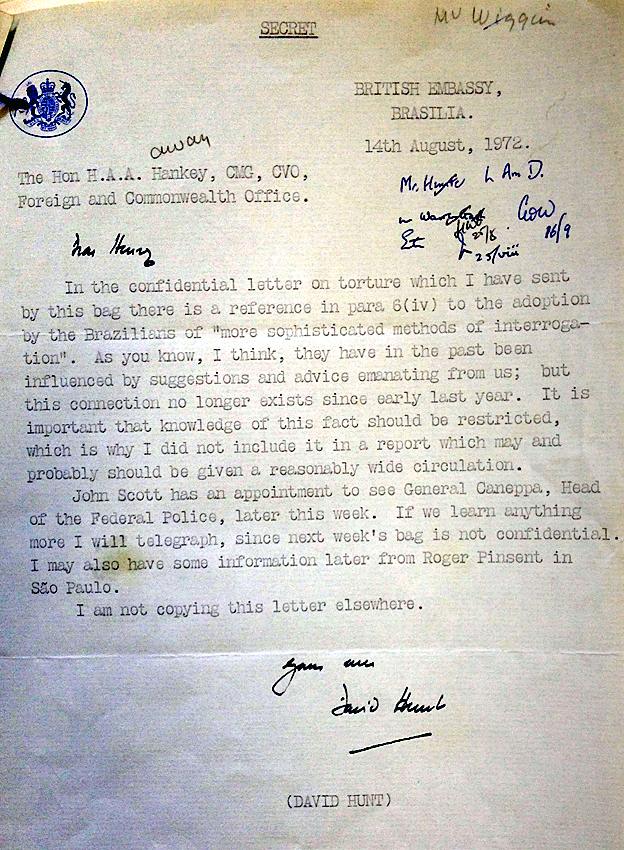

There are more clues to the close relationship between the British and the Brazilian military in the National Archives in Kew.

In August 1972, the then British Ambassador, David Hunt, wrote a secret letter to an official in which, with reference to the Brazilians adopting more sophisticated methods of interrogation, he said:

"As you know, I think, they have in the past been influenced by suggestions and advice emanating from us; but this connection no longer exists... It is important that knowledge of this fact should be restricted."

Then, in the run up to President Ernesto Geisel's 1976 visit to Britain, there are rather more oblique references to a reform of torture. One letter talks of "acceptable standards of interrogation (eg of the kind permitted in Northern Ireland)".

A document entitled "Torture in Brazil" and marked "confidential" speaks of the bad publicity the Army had been receiving and how it had introduced new techniques based on psychological methods.

"The First Army in Rio are now said to be using the new techniques, the introduction of which the Army Commander described as taking a leaf out of the British book."

It's clear from the Foreign Office correspondence that at the time trade and commercial interests were of primary importance and Brazil's poor record on human rights record was downplayed.

Sir Alan Munro, who was Consul General in Rio in the mid 1970s, says he personally had no knowledge of collaboration over interrogation.

"If the Brazilians were looking for techniques of interrogation used by British authorities, the example would have been the early years of Northern Ireland. This would have been undertaken on a Brazilian initiative, and the extent that it might reduce the most brutal methods, it would have been a step in the right direction," he says.

But powerful interrogation methods put in the hands of men for whom torture was routine is not seen in Brazil as a "step in the right direction". The head of Rio's Truth Commission, Wadih Damous, had long known of US support and training for the regime, but he is indignant at the idea of British involvement in psychological torture.

"It is always shocking to hear that a democracy which is so important, so established, so old, collaborated with a dictatorship," he says.

I asked for an official response from the British Foreign Office. A spokesman said it cannot comment on the work of previous administrations but that current government policy ensures that any requests for security and justice assistance work overseas meets the country's human rights obligations.

Emily Buchanan's report was filmed for the BBC programme Newsnight

Additional reporting by Jan Rocha

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external