The country where nearly two-thirds of men smoke

- Published

East Timor has one of the highest smoking rates in the world, with nearly two-thirds of its men hooked on the habit. Why is one of South East Asia's poorest nations so addicted to tobacco?

Tobacco is part of the fabric of East Timor - walking through the dark alleyways of market stalls, the air is sweet with the smell of raw tobacco on sale among the neatly stacked piles of tomatoes, potatoes, squashes and beans.

Most cigarettes cost less than $1 (60p) a packet. They are stacked under large sun umbrellas bearing the logos of various brands, such as L.A. and Vinte e Tres.

All carry health warnings but these are effectively meaningless to many smokers - about half the adult population can't read.

In the capital, Dili, the iconic Marlboro cowboy still rides the range on posters above shops, despite having ridden into the sunset in most other countries where advertising is banned or restricted.

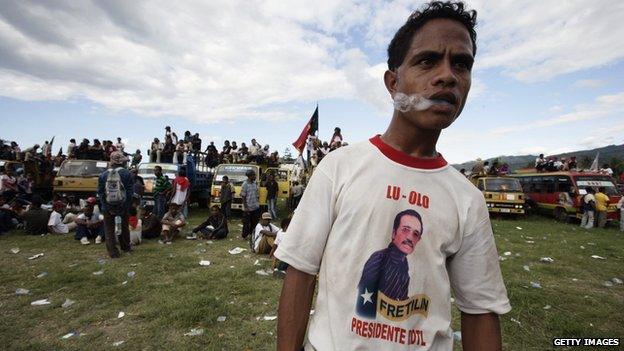

According to figures from the Journal of the American Medical Association, 33% of East Timor's population smoke every day. The figure for men stands at 61% - the highest in the world.

"Young people are smoking more and more each year, especially young boys," says Dr Jorge Luna, The World Health Organisation's local representative. "It is a very serious problem."

Almost half the population is under 15 and increasingly the demand, especially among the young, is for Western-type cigarettes, often sold singly from packets displayed invitingly along the roadside.

"One cigarette is 10 cents, if you buy two it's 20 cents, if you buy four it will be 25 cents," says Luna. Tobacco grown by small-scale farmers for roll-your-own cigarettes is even cheaper than the named brands that are often imported from neighbouring Indonesia.

East Timor's schools have virtually no health education with regard to smoking. "I've witnessed first-hand teachers who smoke while teaching [while] they're there on the blackboard writing," says Luc Sabot, East Timor's director of the Adventist Development and Relief Agency.

"The whole school system has absolutely no regulation on tobacco use in school."

Near one school, I watch a young man, cigarette in hand, sitting astride a motorbike with a Marlboro logo, casually chatting to a young woman.

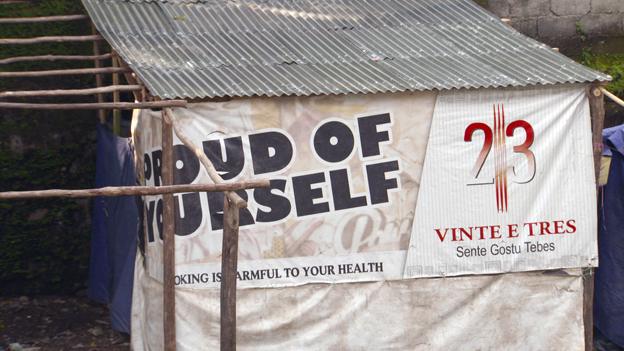

The scene reminds me of a controversial advertising campaign for Vinte e Tres that ran in the capital last year, depicting a cool looking young man, clad in black, on a black motorbike.

The slogan read defiantly "Proud of Yourself". Initially the posters contained no health warnings, and after protests from health campaigners they were taken down.

They were then put back up again, this time with a small warning at the bottom. When the campaign had run its course, some of the banners became improvised wall coverings for tin-roofed shacks.

And in East Timor you can smoke anywhere. The air in bars, restaurants, hotel lobbies and cafes is invariably full of smoke.

There's only one exception - a sparkling new shopping mall owned by a passionate anti-smoker where smoking is prohibited.

Even the prime minister is a heavy smoker. Xanana Gusmao was one of the guerrilla leaders who fought the Indonesians after they had annexed East Timor in 1975 and before the country achieved its independence in 2002.

He was captured and sentenced to life imprisonment before his release prior to independence.

He says that cigarettes kept him and his comrades going when they were fighting in the bush and that an Indonesian bullet was far more dangerous than smoking.

He admits he's an addict, having tried unsuccessfully to give up three times, and admits he's not a good role model.

When I ask him about banning cigarette advertising, he repeats what is tantamount to the tobacco industry's line.

"The law, banning this, banning that, will not be so effective. It needs education [and] it will take time but I believe that the more people are aware of the diseases that it can cause, the more they are able to stop by themselves."

But the prime minister's feisty Australian wife, Kirsty Sword Gusmao, is a committed anti-cancer campaigner,

She had breast cancer herself, and is concerned about the increasing number of young smokers.

"Tobacco companies in Indonesia and elsewhere are targeting very much young people who are conscious of image, conscious of 'the cool factor'," she says.

Some, she says, were as young as 10 and 11.

The tobacco industry, however, always vehemently denies it targets children.

As yet, East Timor's hospitals are not overrun with patients suffering from smoking related diseases as the young have not been smoking cigarettes long enough to incubate them.

At the moment the big killer is tuberculosis but Dr Dan Murphy, an American who's been running a local hospital and clinic in Dili for 20 years, is worried about the future.

Some 80% of the world's smokers live in developing countries and "young people are learning that what they're supposed to do to be Western and advanced is to smoke cigarettes," he says.

"Now we have to change their whole way of thinking and start worrying about tomorrow. I'm afraid we're going to have to go through a phase of learning the hard lesson that's been seen throughout poor countries."

He isn't convinced that the government is serious about tackling the problem - the tobacco lobby, he says, is powerful.

"They can make it seem like [smoking] is something that's a pleasure, something that adds to your life and puts meaning on your life. You're up against a propaganda machine - for cigarettes, smoking and the image. And that's a tough battle."

Watch Burning Desire on BBC Two at 21:30 BST on Thursday.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.