A Point of View: What happens when a library falls silent

- Published

When libraries shut down, what more besides is lost, asks writer AL Kennedy.

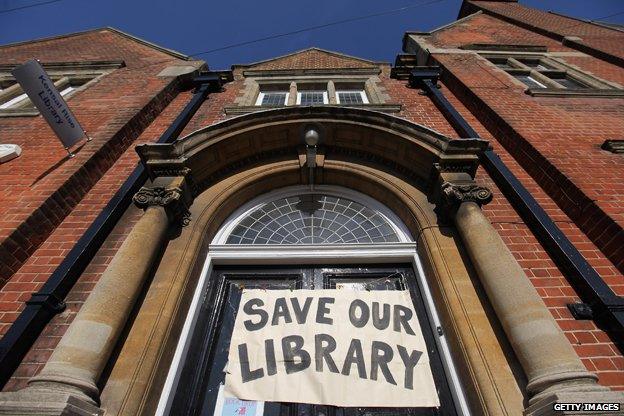

At the end of May, Rhydyfelin Library was closed. Library users chained themselves to the shelves, obtained a judicial review and, to cut a complicated story short, a small Welsh town had to fight to keep its books - and, in the last few days, may have managed at least a temporary stay of execution.

It was dramatic. And yet in terms of national media coverage the drama played out silence, perhaps appropriately for a library. Perhaps it was too regional a story.

And maybe library closures do just slide by, because they often are regional affairs and also because some things which happen repeatedly somehow become less newsworthy.

Certainly, if you examine Britain's library closures the story does get repetitive. According to figures collated by Public Libraries News in the last financial year, 61 libraries were withdrawn from service. The preceding year it was 63, the year before that 201. Some new libraries have opened, but there's debate, again often inaudible, about how many hundreds of others are threatened. Of those 325 lost libraries, around a third have been taken over by their communities in various ways, often with reduced opening hours and working with volunteers.

Volunteers can do a wonderful job - my local library at New Cross Learning is exemplary - but many communities now have a silence where there was a library - no easy access to books for precisely those people who might really need it, no computers to use, no meeting point to enjoy, more silence.

And Britain isn't just losing books because of library cutbacks and closures - a perfect storm of combined pressures means we're losing books on all sides. And that concerns me on more than just the personal level.

Yes, I'm an author, I would care about books. My livelihood relies on downloadable files of information and the more conventional volumes which, according to market researchers Neilsen, are still holding their own - if we exclude data for the titles involved with 50 shades of anything (which one might only feel comfortable reading inside the rechargeable version of a plain cover).

Still, it's not my books I love or feel are especially vital - not in either sense. I hand books I own over to new homes most weeks. And the books I've written - writing a book is like knitting a tricky sweater - you spend so much time on its construction, you rarely want to see it again. It's the epidemic removal of books and even potential books that troubles me.

The child of two academics, I was taught that books should be safeguarded and that wasn't just some sentimental impulse. As the child of two working class people who'd expanded their employment options through education, I was shown books opened like doors into almost unlimited opportunities. And when my mother took me to our local library - Blackness Library, Dundee, it is still there - I found it a high-ceilinged, soft-scented temple of good things yet to happen. Pensioners there reading the papers, enjoying the warmth and presence of company, adults at desks studying, changing their minds almost visibly and children picking out what were still novelties - stories we'd never met. My first ever means of personal identification was my proof of library membership. I was a citizen of the world because I was a reader.

So it's not surprising that if I ask myself, for example, could I burn a book - and book burnings still happen, this century has already seen burnings of the Koran, the Bible, Harry Potter, 8th Century Persian homoerotic poetry and more - well, I don't think I could burn any book. Not even one copy of something shoddy, or dangerous. I couldn't harm a book, even if its contents helped lead Europe into hatred and war, say, even if it had led to the burning of books - those terrifying pyres on Berlin's Bebelplatz and in so many other places.

So why is that? Yes, book burnings are ugly and harm to books has heralded harm to authors, readers, groups of people classified as unacceptable - their thoughts and dreams thrown on to pyres as proof they themselves are expendable, a demonstration of intent. But it can be seductive to think it's good to burn books when they're bad. Why not make ideas I feel are wrong go up in smoke? But what if the ideas I feel are wrong are generally beneficial? What if I'm a bad but persuasive person, preaching hatred and destruction and the end of debate? Then do you burn my words, my books?

Book burning in the Bebelplatz, Berlin, 1933

Well, no. It's important for us to know about ideas that can kill us, to be forewarned, and the fact that ideas are cyclical can help keep us safe - if we maintain access to them. At certain times human beings have promoted feral competition and fear of the unfamiliar while classifying certain groups as parasitic, if not hostile - and I'm able to read about how terribly that can end. And equally I can study how we can invent, collaborate, foster benevolent curiosity towards other cultures and social cohesion. Humanity's past thoughts are my inheritance - I need them in order to learn how to prosper in the long term. They help me deal with other people. Understanding the detail of, for example, racist and bigoted assumptions, and how easily they can be made appealing, can prevent me from being bigoted, even towards bigots. I have a chance to spare myself the re-learning of history's lessons. My reading has taught me those are often painful, sometimes agonising.

Britain is, of course, a stable, democratic country. We may have a surveillance problem, our citizen's online reading choices may be scrutinised, but we have considerable freedom of thought. Yet our access to books isn't just diminishing through the library closures or a culled GCSE reading list. In 1997 the UK lost its net book agreement - which was said to be against the public interest because it fixed prices. Since then, heavy discounts and a recession, mean publishers avoid risks.

So we hear less often from unusual or marginal voices. Less than 3% of books are translations from other languages, other countries. Our range of bookshops and their stock has diminished. If we have computers we'll mainly be offered multiple clones of successful books - and food porn, design porn, 50 shades of soft porn. And celebrity memoirs and misery memoirs will suggest that learning about other people involves being asked to stare at their degradation. There are still superb books out there - I just helped award the Ondaatje Prize to Alan Jonson's excellent memoir This Boy - but with less media coverage and fewer ways to be visible, more and more books simply disappear, or are never published. No burning required.

When I used to work in communities around Glasgow I would meet people who had educated themselves using libraries, or sometimes men who had spent prison terms reading, learning, growing a more positive future. This year, along with poet laureate Carol Anne Duffy, the Howard League and many others, I've been pointing out that reducing prisoners' access to books is unwise. Low staffing levels can already mean prison library access is limited. Blocking books sent in from outside cuts man-hours spent searching books for contraband, but if prisons hope to prepare inmates to function in society without harming others or themselves it's a mistake.

Because books can allow us, more deeply and in more detail than any other art form, to enter into the lives of others. Fiction can persuade me that people have value, which is in the public interest. Fiction can train the imagination in positive ways. And without exercise our imaginations fail - we are always a little in prison. If I can't imagine change, my future is passive, if I can't imagine others as human, I'm dangerous, if I can't imagine myself I become small. How do I know that? Because after a generation of dedicated book suppression, Britain's public discourse prefers threats to facts, blaming to creating. And because I read, I know the silence we've imposed isn't the peace of a library, it brings the quiet of a grave.

A Point of View is usually broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 BST and repeated Sundays 08:50 BST - or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.