Why do so many nations want a piece of Antarctica?

- Published

Seven countries have laid claim to parts of Antarctica and many more have a presence there - why do they all want a piece of this frozen wasteland?

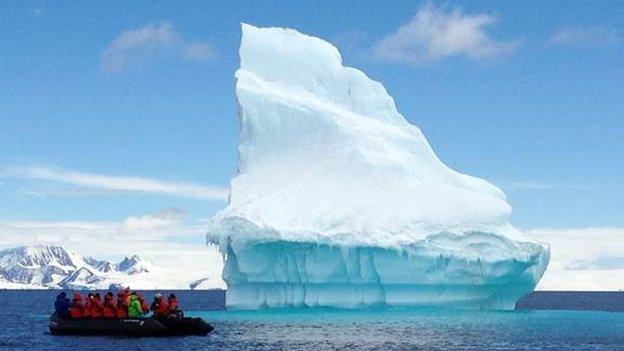

I pick a path between rock pools and settle my bottom on a boulder. A spectacular, silent view unfolds across a mountain-fringed bay.

Then there is a flash in the shallows by my feet - an arrow of white and black.

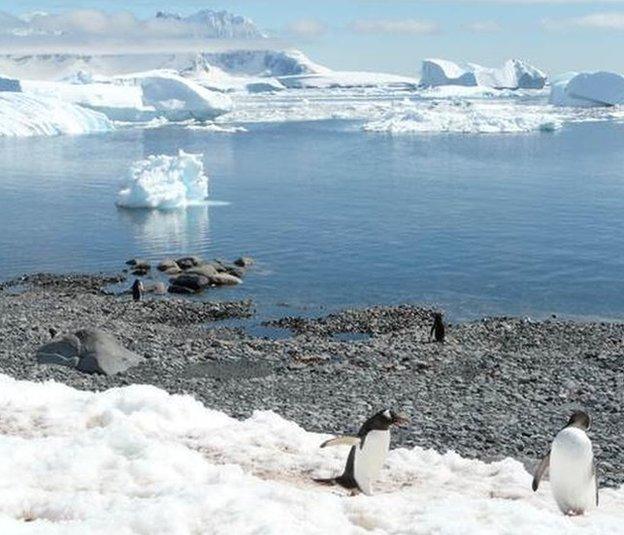

What on earth fish is that? My slow brain ponders, as before my eyes a gentoo penguin slips out of the water, steadies itself on a rock, eyes me cheekily, squawks and patters off into the snow.

Antarctica is the hardest place I know to write about. Whenever you try to pin down the experience of being there, words dissolve under your fingers.

There are no points of reference. In the most literal sense, Antarctica is inhuman.

Other deserts, from Arabia to Arizona, are peopled: humans live in or around them, find sustenance in them, shape them with their imagination and their ingenuity. No people shape Antarctica.

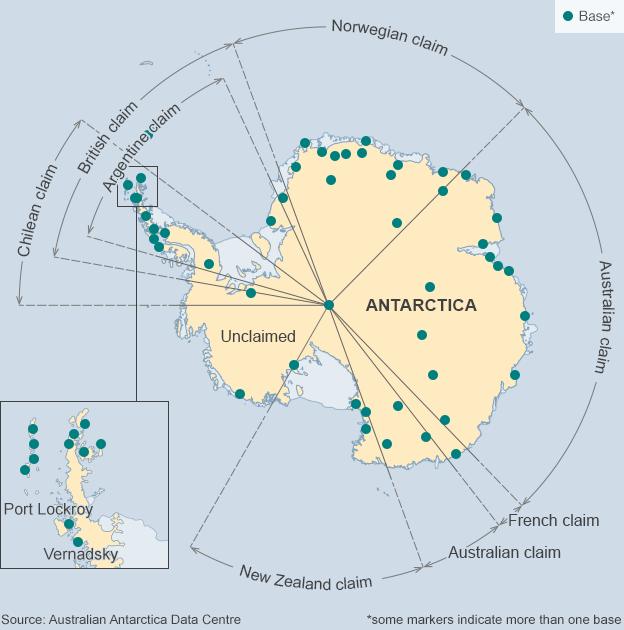

It is the driest, coldest, windiest place in the world. So why, then, have Britain, France, Norway, Australia, New Zealand, Chile and Argentina drawn lines on Antarctica's map, carving up the empty ice with territorial claims?

Antarctica is not a country: it has no government and no indigenous population. Instead, the entire continent is set aside as a scientific preserve.

The Antarctic Treaty, external, which came into force in 1961, enshrines an ideal of intellectual exchange.

Military activity is banned, as is prospecting for minerals. Fifty states - including Russia, China and the US - have now ratified the treaty and its associated agreements.

Yet one legacy of earlier imperial expeditions, when Shackleton and the rest battled blizzards to plant their flags, is national covetousness.

Science drives human investigation in Antarctica today, yet there's a reason why geologists often take centre-stage. Governments really want to know what's under the ice.

Whisper the word: oil. Some predictions suggest the amount of oil in Antarctica could be 200 billion barrels, far more than Kuwait or Abu Dhabi.

Antarctic oil is extremely difficult and, at the moment, prohibitively expensive to extract - but it's impossible to predict what the global economy will look like in 2048, when the protocol banning Antarctic prospecting comes up for renewal. By that stage, an energy-hungry world could be desperate.

The Antarctic Treaty has put all territorial claims into abeyance, but that hasn't stopped rule-bending. The best way to get a toehold on what may lie beneath is to act as if you own the place.

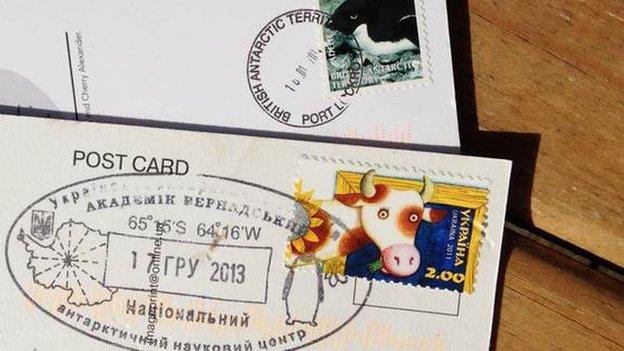

One of the things nation-states do is stamp passports - so when Antarctic tourists visit the British station at Port Lockroy, external, they can have their passport stamped.

This is despite the fact that international law doesn't recognise the existence of the British Antarctic Territory - indeed, both Chile and Argentina claim the same piece of land, and have their own passport stamps at the ready.

Another thing states do - or used to - is operate postal services.

At Ukraine's Vernadsky base, I wrote myself a postcard, bought a decorative Ukrainian stamp with a cow on it, and dropped it into their post box. It took two months to arrive - not bad, from the ends of the earth.

But tourist fun connives at all the flag-waving. Russia has made a point of building bases all round the Antarctic continent.

The US operates a base at the South Pole,, external which conveniently straddles every territorial claim. This year China built its fourth base. Next year it will build a fifth.

All Antarctica's 68 bases are professedly peaceful research stations, established for scientific purposes - but the ban on militarisation is widely flouted.

Chile and Argentina, for instance, both maintain a permanent army presence on the Antarctic mainland, and the worry is that some countries are either not reporting military deployment, or may instead be recruiting civilian security contractors for essentially military missions.

Antarctic skies are unusually clear and also unusually free from radio interference - they are ideal for deep-space research and satellite tracking. But they are also ideal for establishing covert surveillance networks and remote control of offensive weapons systems.

The Australian government recently identified China's newest base as a threat, specifically because of the surveillance potential.

It said: "Antarctic bases are increasingly used for 'dual-use' scientific research that's useful for military purposes."

Many governments reject Antarctica's status quo, built on European endeavour and entrenched by Cold War geopolitics that, some say, give undue influence to the superpowers of the past.

Iran has said it intends to build in Antarctica, Turkey too. India has a long history of Antarctic involvement and Pakistan has approved Antarctic expansion - all in the name of scientific cooperation.

But the status quo depends on self-regulation. The Antarctic Treaty has no teeth. Faced with intensifying competition over abundant natural resources and unforeseen intelligence-gathering opportunities, all it can do - like my penguin - is squawk, and patter off into the snow.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published22 December 2012

- Published19 May 2014

- Published5 January 2014