Esa's Cryosat mission sees Antarctic ice losses double

- Published

Antarctica is now losing about 160 billion tonnes of ice a year to the ocean - twice as much as when the continent was last surveyed.

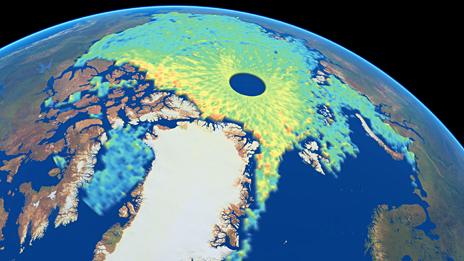

The new assessment comes from Europe's Cryosat spacecraft, which has a radar instrument specifically designed to measure the shape of the ice sheet.

The melt loss from the White Continent is sufficient to push up global sea levels by around 0.43mm per year.

Scientists report the data in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, external.

The new study incorporates three years of measurements from 2010 to 2013, and updates a synthesis of observations made by other satellites over the period 2005 to 2010.

Cryosat has been using its altimeter to trace changes in the height of the ice sheet - as it gains mass through snowfall, and loses mass through melting.

'Big deal'

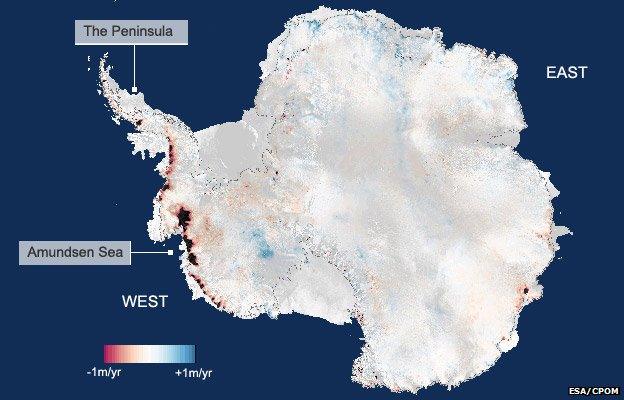

The study authors divide the continent into three sectors - the West Antarctic, the East Antarctic, and the Antarctic Peninsula, which is the long finger of land reaching up to South America.

Overall, Cryosat finds all three regions to be losing ice, with the average elevation of the full ice sheet falling annually by almost 2cm.

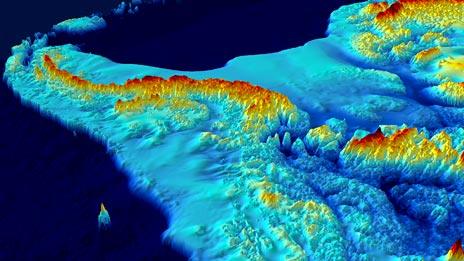

Cryosat's double antenna configuration allows it to map slopes very effectively

In the three sectors, this equates to losses of 134 billion tonnes, 3 billion tonnes, and 23 billion tonnes of ice per year, respectively.

The East had been gaining ice in the previous study period, boosted by some exceptional snowfall, but it is now seen as broadly static in the new survey.

As expected, it is the western ice sheet that dominates the reductions.

Scientists have long considered it to be the most vulnerable to melting.

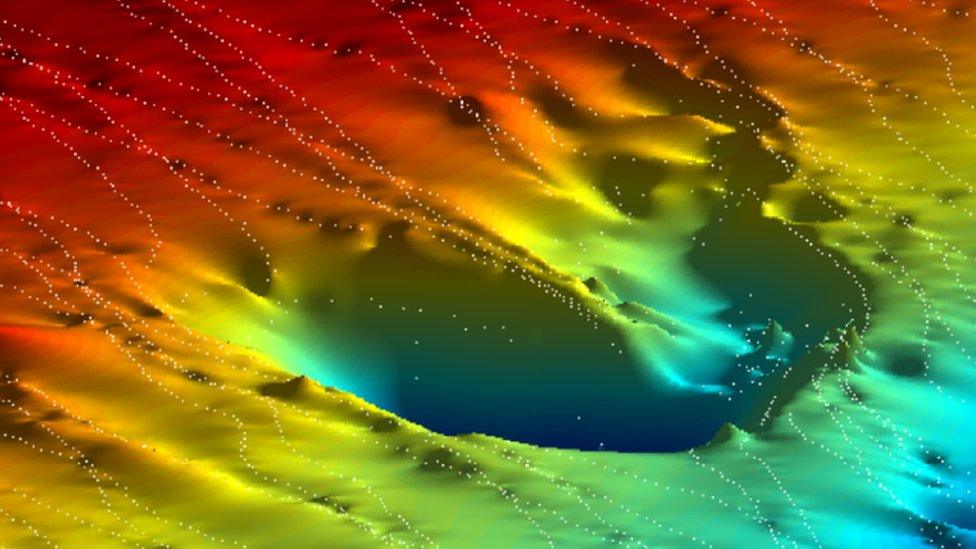

It has an area, called the Amundsen Sea Embayment, where six huge glaciers are currently undergoing a rapid retreat - all of them being eroded by the influx of warm ocean waters that scientists say are being drawn towards the continent by stronger winds whipped up by a changing climate.

About 90% of the mass loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is going from just these few ice streams.

At one of them - Smith Glacier - Crysosat sees the surface lowering by 9m per year.

Some western ice streams such as Pine Island Glacier are retreating and thinning rapidly

"CryoSat has given us a new understanding of how Antarctica has changed over the last three years and allowed us to survey almost the entire continent," explained lead author Dr Malcolm McMillan from the NERC Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling, external at Leeds University, UK.

"We find that ice losses continue to be most pronounced in West Antarctica, along the fast-flowing ice streams that drain into the Amundsen Sea. In East Antarctica, the ice sheet remained roughly in balance, with no net loss or gain over the three-year period," he told BBC News.

Cryosat was launched by the European Space Agency in 2010, external on a dedicated quest to measure changes at the poles, and was given a novel radar system for the purpose.

It has two antennas slightly offset from each other. This enables the instrument to detect not just the height of the ice sheet but the shape of its slopes and ridges.

This makes Cryosat much more sensitive to details at the steep edges of the ice sheet - the locations where thinning is most pronounced.

It also allows the satellite to better detect what is going on in the peninsula region of the continent where the climate has warmed rapidly over the past 50 years.

"The peninsula is extremely rugged and previous satellite altimeters have always struggled to see its narrow glaciers. With Cryosat, we get remarkable coverage - better than anything that's been achieved before," said Prof Andy Shepherd, also of Leeds University.

Future change

The GRL paper follows hard on the heels of two studies that have made a specific assessment of the future prospects for the Amundsen Sea Embayment.

One of these reports concluded that the area's glaciers were now in an irreversible retreat.

The other paper, considering one of the glaciers in detail, suggested the reversal process could take several hundred years to be completed.

A loss of all the ice in the six glaciers would add about 1.2m to global sea level.

This is still a small fraction of the total sea-level potential of Antarctica, which holds something like 26.5 million cubic km ice (or 58m of sea-level rise equivalent). But the continent has been largely insulated from some of the warming influences taking place elsewhere in the world and it is important, say scientists, to keep a check on any changes that are occurring, and the speed with which they are happening.

Prof Duncan Wingham proposed the Cryosat mission and is its principal investigator. He told BBC News: "We lack the capability to predict accurately how the Amundsen ice streams will behave in future.

"Equally, a continuation or acceleration of their behaviour has serious implications for sea level rise. This makes essential their continued observation, by Cryosat and its successors."

Prof David Vaughan of the British Antarctic Survey, who was not involved in the Cryosat survey, commented: "The increasing contribution of Antarctica to sea-level rise is a global issue, and we need to use every technique available to understand where and how much ice is being lost.

"Through some very clever technical improvements, McMillan and his colleagues have produced the best maps of Antarctic ice loss we have ever had. Prediction of the rate of future global sea-level rise must begin with a thorough understanding of current changes in the ice sheets - this study puts us exactly where we need to be."

The Antarctic Peninsula's rugged terrain has made radar measurement very difficult in the past

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 May 2014

- Published14 January 2014

.jpg)

- Published13 December 2013

- Published11 December 2013

- Published2 July 2013

- Published29 November 2012

- Published24 April 2012

- Published5 December 2011