Hope for the future in Brno's Jewish cemetery

- Published

The Jewish cemetery in the Czech town of Brno bears witness to the region's turbulent history, but it also holds a message of hope for the future, writes the BBC's Chris Bowlby.

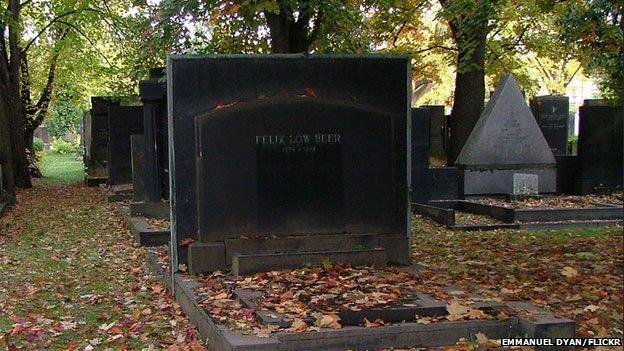

I strolled at first among a place of elegant good order - neat rows of gravestones beneath a canopy of fine trees. And it seemed like the record of a community of stability and steadily growing prosperity - memorials to Jewish families who helped make Brno - or Brünn as it was widely known - a textile powerhouse. This place, not far from Vienna, was known in the 19th Century as the Austro-Hungarian Manchester. And the community prospered in many other professions too. Lawyers, head teachers, intellectuals and actors are buried here. I noticed Kafkas and Schillers among the names. The German-speaking world of commerce and culture so influential in central European history is proudly on display.

As is a gift for architecture and design. Heavier 19th Century tombstones are mixed with more modern shapes and elegant 20th Century lettering. This community relished the opportunities of an economically dynamic new Czechoslovakia created after World War One. Even in their gravestones, I noticed, was a modernist faith in a future they'd helped to create. Prosperity begun with textiles would, it was assumed, weave together this place's peoples and cultures, despite the unravelling threatened by big-power politics all round.

But then I stopped strolling, confronted with a horrific interruption to that narrative of progress. Gravestones that began conventionally enough, with, say, parents' names and dates of birth, then switched from ornate lettering to cold, despairing lament. Now no careful recording of date or place of death, considered epitaph, record of a life fully lived and brought to a proper end. Instead, only the dates of when each group of parents, children, grandchildren disappeared into the terrible anonymous void of deportation and Nazi death camps somewhere to the east. Here the beautiful trees and intense spring birdsong all around seemed cruelly inappropriate for such a bleak conclusion.

That interruption is underlined by change of language too. As the story moves from stability to catastrophe you no longer see German inscribed, but Czech. Did this community feel, I wondered, that their ancestors' language had been permanently corrupted? Had German become the unbearable mark of Nazi brutality, no longer the language that recorded this cultured community's successful assimilation? For some time after the war the Jewish presence in Brno all but disappeared. The few who survived deportation never felt welcome, especially after the communists took over Czechoslovakia. Many left for Israel.

But since the end of communist rule in 1989, the Jewish presence has been reviving. And so has the memory of what previous generations built here with optimism and imagination. At the Villa Tugendhat in another suburb I found the revolutionary interwar residence commissioned by a local Jewish couple from the architect Mies van der Rohe.

Traditionally heavy Czech villas still stand around it. But gazing at its luminous expanse of glass and concrete, with rigidly clean lines free of any decoration, I sensed what a stir it must have caused when first built. Its owners had to flee in 1938 as the Nazi threat to Czechoslovakia loomed. But in the last few years the building, reopened after restoration, is now under Unesco protection, and maintained by an impressive young staff well versed in its significance, with plans to expand its educational role and tourist potential.

Mies Van Der Rohe

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe (1886-1969), German-American considered one of 20th Century's greatest architects

Tried to reflect modern life through use of materials such as plate glass and steel

Most famous buildings include Villa Tugendhat (pictured) in Brno, and Seagram Building in New York

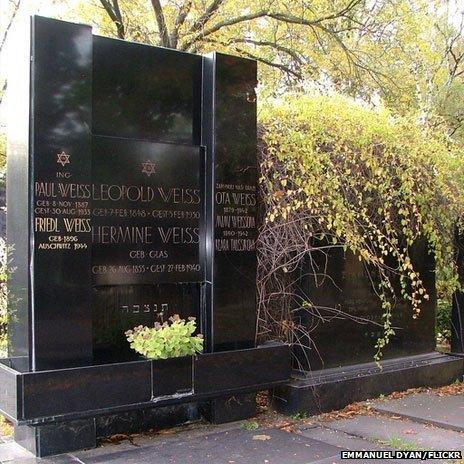

At the Jewish cemetery, its buildings also impressively restored, was a tall young attendant, eager to please, gesturing towards tables loaded with publications and information. He told me about a new business - tours organised by his community highlighting their history. It was such a cheering contrast to other Jewish cemeteries I've seen in the region, where exhausted older community members struggle to keep going, or where, as in Vienna, decades of shameful neglect by the city left the resting place of many of its greatest residents full of collapsing or vandalised tombstones and weed-infested plots.

Vienna's Jewish cemetery in 2007

But in Brno the newest generations from Jewish and other communities are trying again to make the mingling of peoples in this European crossroads a creative force. In the city centre, Ukrainian and Russian students are among those honing their business or language skills in classrooms together. They know better than anyone that the threat of conflict is never completely buried. It resounds in this city's memory - not only of Nazis and communists, but in cathedral bells, ringing out a reminder every day of the brutal 17th Century siege by protestant Swedes, or the major Napoleonic battlefield at Austerlitz nearby. Yet I will be remembering, in a beautiful cemetery, not only awful history but also the spirit of a community that still believes it can honour the past by creating a successful future.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.