Poland's overlooked Enigma codebreakers

- Published

The first breakthrough in the battle to crack Nazi Germany's Enigma code was made not in Bletchley Park but in Warsaw. The debt owed by British wartime codebreakers to their Polish colleagues was acknowledged this week at a quiet gathering of spy chiefs.

On the outskirts of Warsaw, some of the most senior spy bosses from Poland, France and Britain gathered this week in a nondescript but well-guarded building used by the Polish secret services. Their coming together was a way of marking the anniversary of a moment three-quarters of a century earlier when their predecessors held a meeting in Warsaw that played a crucial role in the victory over Hitler in World War Two.

Seventy-five years ago, two British intelligence officers - Alastair Denniston and Dilly Knox - had got off a train at Warsaw's central station. The two Britons were veterans of the Government Code and Cypher School, which would move to Bletchley Park as the war began.

Europe was on the eve of war. Denniston had decided he wanted to see Germany for one last time before the conflict began and so they had made their way via Berlin. If the Germans had known who he was, and the reasons for his trip, they may not have been so forthcoming with their visa. He was travelling to Poland to try to discover the secret of how to break the Enigma machine that Germany used to encode military communications.

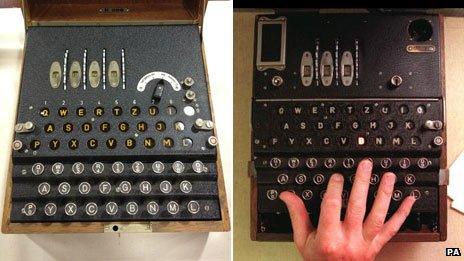

The Enigma machine

Rotors at top left could be rotated to different settings, to generate different codes - more rotors made the code more difficult to crack

The message was typed into the machine using typewriter keys at the front

Each time a letter was typed a lamp lit up one of the letters in the middle of the machine - this illuminated letter then formed part of the cipher text

Later models, such as the German military machine on the right, had a plugboard at the front (under the operator's hand), which added an additional level of complexity

After leaving the station, the two Britons headed out to a secret facility at Pyry in a forest outside the city. British, French and Polish codebreakers had already met once, earlier in the year, but that meeting had ended in stalemate. The French had acted as intermediaries but neither British nor Polish had then been willing to show their hand. By July 1939, with war looming, that had changed.

British codebreakers had enjoyed a few successes against early Enigma machines in the mid-1930s but as war approached they had hit a cul-de-sac. The Poles were far ahead thanks to some remarkable breakthroughs (successes that so infuriated Knox he threw a tantrum). Whereas Britain still used linguists to break codes, the Poles had understood that it was necessary to use mathematics to look for patterns.

They had then taken a further step by building electro-mechanical machines to search for solutions (known as "bombas", perhaps because of the ticking noise they made). These devices simulated the workings of an Enigma machine, and enabled operators to search for the settings of the Enigma that had encoded the message, by cycling through one possible setting after another. This worked until the Germans increased the sophistication of the machine.

It was the sharing of this understanding that the Britons would take back home. In turn this allowed Bletchley's own mathematical genius Alan Turing, who would meet with the Poles himself later, to develop his own "bombe" capable of breaking the more complex wartime Enigma codes. One new technique that made the bombe more powerful was the use of "cribs" - assumed or known parts of the message - as a starting point.

This work at Bletchley is reckoned by some estimates to have shortened the war by as much as two years and saved countless lives.

Representing Britain at the modern-day ceremony was the head of GCHQ, the intelligence agency that grew out of Bletchley Park. "What happened here in 1939 changed the course of history and we are here to honour those who are responsible," its director Sir Iain Lobban told the audience.

He described the breaking of Enigma as like a relay race in which the baton has been passed "but it is the team as a whole which wins the medal". At the ceremony, with an Enigma machine on display, relatives of the three Polish mathematicians who pioneered the solutions - Jerzy Rozycki, Henryk Zygalski and Marian Rejewski - were visibly emotional as tributes were paid.

Polish codebreakers

Jerzy Rozycki, Henryk Zygalski and Marian Rejewski studied maths at Poznan university and later joined the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau in Warsaw

When the war broke out they were evacuated to France - and for a while worked under cover in Vichy France

Rozycki died in 1942 on a passenger ship that sank, for reasons that are unclear, in the Mediterranean

Rejewski and Zygalski fled to Spain in late 1942 and were smuggled to the UK by British agents

In 1946 Rejewski returned to Poland to work as an accountant - he died in 1980

Zygalski remained in the UK working as a maths lecturer at the University of Surrey - he died in 1978

The French secret service had become involved because it had an agent inside Germany providing details of the workings of the Enigma machine, which in turn were fed to the Poles.

"The first lesson is of course that working together we succeed much more," Patrick Pailoux, the technical director of the French secret service, the DGSE, told the BBC. "But another issue is mixing the best scientists with classical intelligence work - what we call the human intelligence. So putting all the capacities together you succeed much more. That's what we have done in the Second World War and that's still the case."

A 1944 Enigma code book on sale at Bonhams in New York last month

Poles have often felt their crucial role in breaking Enigma has been overlooked and the event was partly about acknowledging their contribution. But it also has contemporary relevance for a country that saw Nazi invasion and then Soviet domination in the wake of the July 1939 meeting.

"We are still a very young democratic intelligence service. So we try to introduce tradition to the work of our intelligence agents," Gen Maciej Hunia, who runs Poland's external intelligence service, told the BBC.

"The traditions of Polish intelligence agencies before the Second World War are very important to our newcomers - to see real successes. So for that reason the Enigma story is so very important."

After their short stay in Poland 75 years ago, the two British codebreakers took their train home through a Europe that would descend into war just a few weeks later. But the course of the war would be changed by the knowledge they carried with them.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.