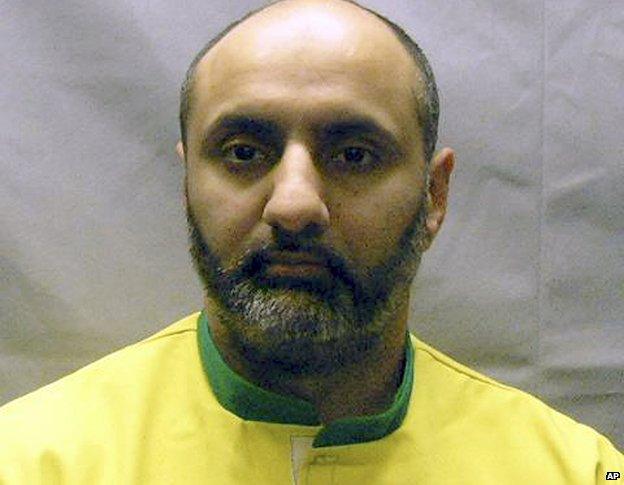

Babar Ahmad: The godfather of internet jihad?

- Published

This week has seen the jailing of a man the Americans consider to be one of the most dangerous facilitators of terrorism in the West. But he is likely to be free in less than a year. He was a pioneer when it came to using the web as a tool of jihadist propaganda. So why do thousands of people think that Babar Ahmad is a victim of an injustice?

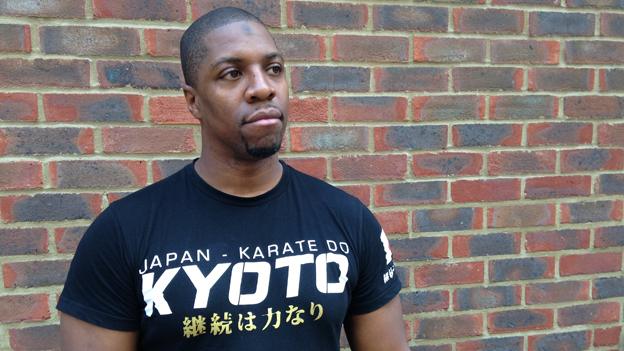

If you wanted to find the face - and voice - of Generation Jihad, it would be Babar Ahmad.

A decade in jail fighting against conviction, he finally accepted last year that he had committed terrorist offences in 1990s London.

Ahmad pleaded guilty in an American courtroom to providing support for terrorism. The US authorities say that he ran a support network in south London which had near-unprecedented global reach. But his story is more complicated than that - the judge sentencing him concluded he was no international terrorist.

And at the heart of his network was a website - the first in English to spread jihad. The US says his network not only spread a dangerous ideology - it encouraged young Muslims to join al-Qaeda and turn their face against the West.

Behind these headlines is a story of a young British man struggling with his identity in the 9/11 age - a story which is still being played out by others today.

In the early 1990s, Babar Ahmad, who was educated at the exclusive Emmanuel School in Battersea, south London, co-founded an Islamic study group called the Tooting Circle. The teenagers who would get together for his talks would meet in each others' houses or in a local mosque that was often empty - and more often than not in the Chicken Cottage takeaway on the High Street.

The restaurant in Tooting, south London, where Ahmad held Islamic study group meetings

But according to the Americans, there was a secret layer to this group - one that used safe houses and coded messages. And it is those events that led to this bright young man from a loving home being jailed.

Andrew Ramsey met Babar Ahmad when he was 14.

"I was a Christian at the time and deeply religious and I had friends who had a similar devotion but at the Islamic end and we exchanged notes," he says. "He was a straightforward guy, a guy you would hang out with, very friendly and polite. My mother noted him for impeccable manners."

Ahmad came from an upwardly-mobile British-Pakistani home with education and ambition at its core. His mother was a teacher and his father a civil servant. Ahmad was a natural leader - and those skills came out in the Tooting Circle where he would tell his peers about how to live a good and honourable life, following the model of the prophet Mohammad.

Babar Ahmad aged six, with his younger sister

Andrew Ramsey, whom Ahmad helped convert to Islam, says community elders didn't want the meetings in their mosque because they objected to some of the subject matter of the discussions in the prayer hall.

"At the time it was all about getting young people away from the pitfalls of being a teenager," he says. "Girls, parties, drink, that kind of thing - and into having a discipline where you are doing things in a Godly manner, so to speak."

So why did the US Department of Justice spend a decade trying to bring this earnest young man to justice? They say it's about how his ideology changed and what he did with it - and to understand that it is necessary to go back to a terrible moment in modern European history.

The Bosnian War that began in 1992 shocked the world. TV pictures showed Serbian soldiers killing white-skinned European Muslims. While the international community prevaricated, Muslims in Britain saw genocide on their doorstep - a new holocaust within living memory of the Nazis.

The war in Bosnia - and the threat to fellow Muslims - radicalised Babar Ahmad

Their fears fed into an already tense debate within young Muslims about the place of Muslims in the West.

Usama Hasan is a cleric and former jihadi who was part of that intellectual conversation. "Throughout the 80s and 90s there was a huge resurgence in Muslim identity amongst my generation," he says. "We were caught often between two worlds - the world of our parents and home communities, usually from Pakistan or Bangladesh or India or the Arab world who were devout traditional Muslims.

"We were living and being brought up in an increasingly secular post-religious Western British environment.

"And that had caused an identity crisis. Many of our generation decided to solve this identity crisis by firmly adopting political Islam and becoming not only devout Muslims but highly politicised Muslims and connecting with that resurgence of political Islam around the world."

Babar Ahmad describes his experience fighting in Bosnia, in a 2011 interview

Babar Ahmad adopted that identity. And now, in talks across London and other cities, he and others applied it to the horrors of Bosnia. He split from the mainstream, frustrated by inaction, and said there was one priority - armed jihad. And aged just 18, this student at Imperial College London - one of the world's finest Universities - went to fight.

Over the next three years Ahmad fitted in volunteering in the Bosnian war around his university studies. He returned something of a local hero - not least because he received a shrapnel wound to the head.

Youngsters would flock to hear him talk. He had become a key figure in Imperial College's influential Islamic Society - an important forum in the debate over Muslim identity in the West.

Nothing Babar Ahmad did in Bosnia was illegal - he had risked his life to save others from slaughter. Even some mainstream commentators at the time compared the moral courage of the Brits in Bosnia to the foreign brigades in the Spanish Civil war sixty years before.

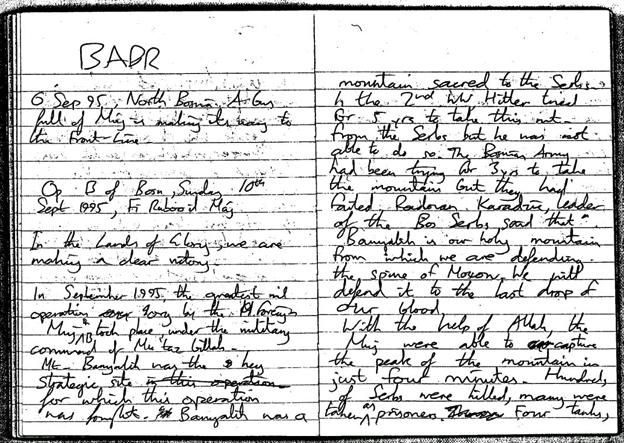

Ahmad's Bosnia journal: "In the lands of glory, we are making a clear victory"

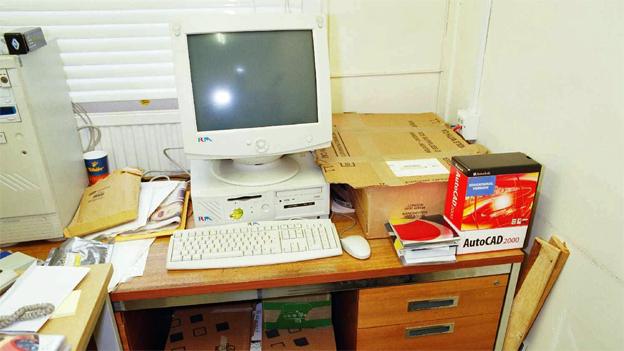

But according to the Americans, after the war ended, Ahmad's ideology, full of pity for the victims - and fury at the world - took a fateful turn. Now working for his former university, he spent long hours tapping away at his office computer. In 1996, he launched Azzam Publications. This was the first English language website dedicated to jihad.

It has now long since disappeared from the web, but the site declared that its purpose was to propagate a call to arms "among the Muslims who are sitting down ignorant of this vital duty".

"Fight in the cause of Allah," it said, "incite the believers to fight along with you."

He and others working with him also produced video and audio tapes in English of the stories of Muslims killed in the war - The Martyrs of Bosnia was the first and most important of these.

These tapes were distributed around the UK, along with more complex sermons from clerics who were at the forefront of supporting jihad.

Babar Ahmad's office - where he launched his website dedicated to jihad

One of the tapes was called In the Hearts of Green Birds - more stories of martyrs and battles in Bosnia. Babar Ahmad was the narrator, and this tape - and the ideas in it - took on a life of their own.

The 7/7 London suicide attackers had this tape and others from Azzam - and today quotes from it can still be found on social media posts by British fighters in Syria.

Elsewhere, the website included a copy of Osama bin Laden's 1996 "declaration" of war against the West. It also made open appeals for Muslims to send help to the Taliban.

Tom Ridge was the Secretary of Homeland Security in the United States when Ahmad came under investigation. I asked him why Washington was interested in an arcane website managed in London.

"The advocacy, the recruitment, the proselytising and the support of terrorists had found a new medium, a new method of communication through the internet," he says.

"It was striking how effective he was. For every fighter on the ground, for every terrorist, there's a support network.

"You don't have to be pulling a trigger or releasing the power of an IED to be supporting terrorism."

Babar Ahmad is led into court, 2009

Late last year, Babar Ahmad entered a plea bargain agreement with the US Department of Justice. He admitted that his website and activities had provided material support to terrorists, including seeking donations for the Taliban.

The US says that prior to 9/11, Ahmad used safe-houses in Tooting and established a route to get recruits into Afghanistan.

Prosecutors say he used sophisticated counter-surveillance techniques - such as codes and false identities - to cover his tracks online and in the real world.

Babar Ahmad's childhood friend Andrew Ramsey, who freely admits he went to Afghanistan, rejects this.

Andrew Ramsey was a childhood friend of Babar Ahmad

"Yeah, I read comic books too you know," he says. "It wasn't a thing where 'Let's team up and become these wicked terrorists, we'll call ourselves Crimson Jihad, and we are going to blow everywhere up.' It wasn't like that… 'We're going to turn on John, Mary and Sue and blow up the next chip shop,' it wasn't like that."

Despite the plea bargain, prosecutors sought the highest possible sentence and deployed what they regarded as their trump card. They had the testimony of a British man, a would-be suicide bomber turned supergrass.

In 2001 Saajid Badat, a former grammar school boy from Gloucester, trained in Afghanistan to blow up a plane with an al-Qaeda shoe bomb.

But he had a remarkable change of mind and later admitted everything to the police. His eventual jail sentence was cut in return for offering to testify against other members of al-Qaeda.

Badat told investigators that he had been inspired by In the Hearts of Green Birds - and later became part of Babar Ahmad's group. He claimed the London man then asked him to go to Afghanistan and help welcome others arriving from London. His account did not state that Ahmad was sending men to join al-Qaeda.

Al-Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan, 2001

Two years ago, I interviewed Babar Ahmad in his British prison while he was still fighting extradition - I wanted to find out what he had to say for himself.

"I never went to Afghanistan, I never lived under the Taliban and I was not familiar with them, I don't know anything about them," he says.

"I have nothing to do with al-Qaeda, and al-Qaeda has nothing to do with my case. I have not looked into and studied their ideology but my position is that killing innocent people is absolutely wrong no matter who does it and what their justification for it.

"(With) 9/11, like most of the world I was shocked at those events. Those feelings were amplified when I found out that a relative of mine was killed. And the same thing for the 7/7 attacks. I was shocked like the rest of the country. My sister missed one of those Tube trains by two minutes."

"I actually find it extremely offensive to be called a terrorist supporter because there is no allegation that is more serious than the allegation of terrorism. And in my life I have never supported terrorism, I have never financed terrorism. I believe that the targeting and killing of innocent people I believe that to be wrong, whatever the circumstances, whatever the justification, whoever does it."

Babar Ahmad tells the BBC his views on Al Qaeda and Jihad (Archive interview, 2012)

Can these two versions of events - the American accusations and the suspect's denials - be reconciled, or is Babar Ahmad simply a liar?

Andrew Ramsey says the atmosphere in London in 1999 excited young Muslims. Many men like him believed the Taliban appeared to be forming a genuine Islamic government and wanted to go and see it for themselves. Ramsey says he had no idea how it would turn out.

Babar Ahmad helped him go to Afghanistan, via a Taliban contact in Pakistan. Ramsey has never been accused of wrongdoing. He says that he attended Arabic classes in Kabul and Jalalabad.

Jihad was among questions the young convert wanted to explore - and he met some Londoners who wanted to fight.

Did Babar Ahmad send him for violent jihad?

"No - because that's not what he has promoted," he says. "We have been friends for a long time. I know that friends can turn but as far as I am concerned no, he was not that way inclined. Never once did I ever (see) him promote, encourage or push for the killing of anyone."

So jihad was the talk of the town in London in 2001.

Jihad

Jihad is an Arabic noun meaning struggle; a person engaged in struggle is a mujahid, and the plural is mujahideen

Muslims refer to the inner struggle of the believer to fulfil their religious duty as the greater jihad

External attempts to build a better community or society are classified as the lesser jihad

The lesser jihad is often taken to mean holy war - the duty to struggle against the enemies of Islam, whether by peaceful or violent means

One source from Tooting told me that Ahmad and his friends were so wrapped up in this fervour that they were "desperately seeking jihad" - but they often didn't know what it really meant.

Usama Hasan, a cleric and expert in "de-radicalisation", says Ahmad came to see him after the 9/11 attacks. He would have known that Usama had once fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan. He wanted answers.

"He asked me about people plotting to commit terrorist actions or Jihadist operations in Britain.

"His question was: 'What if you hear about it from Brothers - Muslims who are plotting to blow up, say, buses or Tubes in this country? What should you do? What is your religious duty?'

"I think he knew, as I knew, that you have a duty to innocent people, to your fellow citizens. But there was this complication for Islamists about loyalty to Muslims, so should you hand over Muslims to the police?

"This was the dilemma. I went to religious scholars in this country and I got a firm answer from them. You must do whatever it takes to stop terrorist action. And I conveyed that to Babar."

Did Babar Ahmad follow his advice?

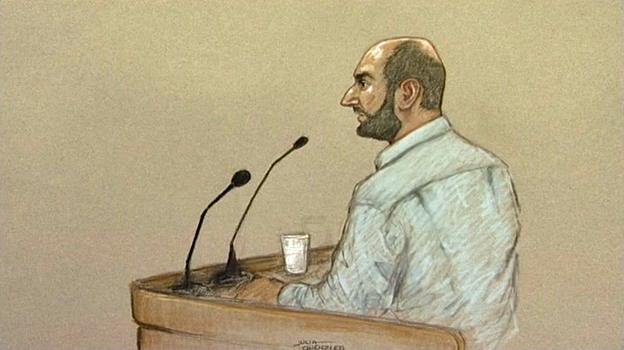

Court sketch of Ahmad giving evidence in extradition proceedings, 2011

"I don't know. I honestly don't know."

In the wake of 9/11, there were competing visions of jihad alive in London. One was defensive - the right to take up arms to prevent oppression. The other was offensive: Osama bin Laden's indiscriminate violence and hatred dressed up in religious clothes. When I met Babar Ahmad in prison in 2012, he told me what he thought.

"If by jihad you mean defending yourself and your home and your family then of course I support that," he said. "Every human being should have the right to defend their home and family and themselves.

"But if one means by that attacking innocent people, or blowing up nightclubs or violence or political means, then I don't support that."

Saajid Badat - the supergrass - provided evidence to support what Ahmad told me in that interview. Despite appearing for the prosecution, he told the court that he didn't want to testify against his former mentor - because he did not believe that Ahmad had ever supported al-Qaeda.

Back in 2001 the net was tightening. MI5 officers interviewed Babar Ahmad and bugged his home - a sign that they were really worried.

Two years later the Metropolitan Police arrested him - only to release him without charge. He was seriously assaulted during that raid - and Scotland Yard admitted liability and paid him £60,000 compensation.

The injuries which Babar Ahmad suffered during his arrest in 2003

That raid had a hugely damaging effect on relations with Muslims in London.

Multiple sources have told me that Babar Ahmad's behaviour changed - his mood soured dramatically. Eyewitnesses have told me that he would tell sympathisers that there was now a "war against Islam".

In 2004, the police were back again, this time with an extradition request from the American authorities. The legal basis for this was simple, the fact that Azzam.com was hosted on servers in the United States.

Police stand outside Babar Ahmad's house shortly after his arrest in 2004

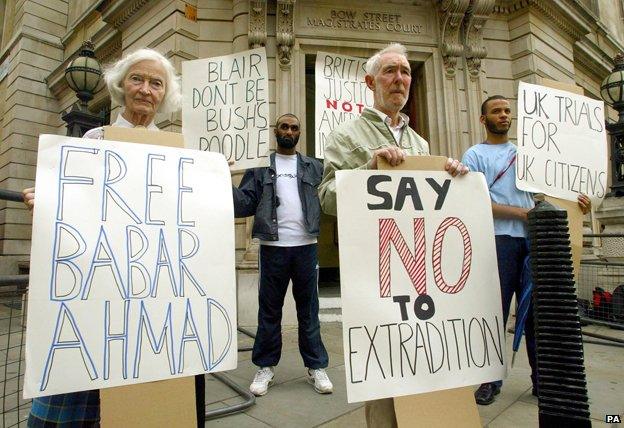

That triggered his much-publicised eight-year-battle to stay in the UK. Almost 150,000 people supported him in an official petition.

Alongside Ahmad, the American authorities sought a second Tooting man, Syed Talha Ahsan. He was accused of helping to run Azzam and also entered into a plea bargain agreement.

His brother, Hamja, described the relationship between the two convicted men: "They were marginal friends. Talha wasn't Babar's number two, he's not even his 99."

The US can say the extradition was just because Ahsan pleaded guilty, but his supporters believe there was a very limited case to answer.

They argue that his diagnosis of a form of autism was a reason to halt his extradition, just like it was in the case of alleged super-hacker Gary McKinnon.

What's more, Hamja Ahsan says the kind of activity both men were involved in - broad and loose support for militant Islamic causes - was common currency 20 years ago. Nobody thought they were doing anything wrong.

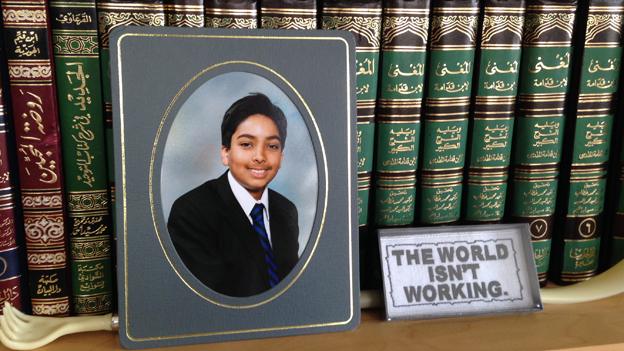

A photo of Syed Talha Ahsan as a boy

Like Andrew Ramsey, Ahsan went to Afghanistan long before 9/11 - and later wrote about his shocking experiences of witnessing fighting and death between the Taliban and its enemies.

"You might go and get a haircut in a Tooting barber shop and they [would] talk about some sort of idealistic thing happening in Afghanistan," he says.

"It was quite even banal to travel to Pakistan and Afghanistan, I think thousands of British Muslims did.

"Talha would have been about 19 years old. Afghanistan was just like a hyped-up state. I would say it was like a rites-of-passage, scholarly interest for hundreds of British Muslims at the time. It was nothing particularly dangerous or harmful at the time."

During the American court case, prosecutors stressed that Talha Ahsan was one of Ahmad's recruits on a journey to terrorism - but the sentencing judge rubbished these claims as exaggerated.

Hamja Ahsan says the way jihad has been presented gets to the heart of the problem.

"A lot of those arguments [about jihad] are bogus arguments by so-called experts and security think-tanks which don't have a grass roots, nuanced understanding of how people were like in the 1990s.

"Sadly, that's the only history being written because people are too scared to speak openly."

Ahmad and Ahsan have now been sentenced. The Americans presented him in court as a terror mastermind who placed men on a conveyor belt to al-Qaeda.

Before he was sentenced, Babar Ahmad admitted he had been wrong to support the Taliban. He said he was driven by idealism and religious fervour - and he now knew that the world was a more complicated place.

But in a last twist in this tale - the judge sentencing Babar Ahmad not only concluded he wasn't an international terrorist, she cast doubt on the reliability of the supergrass evidence.

Ahmad's sentence of 12-and-a-half years reflects her assessment. Ahsan is going free because of his time served while on remand. Ahmad is likely to be back in the UK within months because of the time he has spent in prison. What will happen to him when he returns?

Jihadist groups around the world

What is left of "Core al-Qaeda", as it is known, is believed to be based in Pakistan's tribal region after fleeing Afghanistan in 2001.

But the world's counter-terrorism officials have little cause to celebrate.

Rather than eliminating al-Qaeda, they have caused it to atomise and disperse, morphing into several different organisations around the Middle East, Africa and Asia, with large numbers of jihadist sympathisers in Europe.

Ahmad's former friend Usama Hasan now works for the Quilliam Foundation which advises governments on how to combat extremism. He says the intellectual and religious struggle that Babar Ahmad faced is being repeated today over Syria. He says today's militants need to hear from Babar Ahmad.

"My firm view, knowing Babar for several years, is that he could be one of our biggest assets. His charisma, his experience and because he had an almost martyrdom status among many Muslims in this country.

Ahmad's supporters protest against his extradition outside Bow Street Magistrates, 2004

"He is widely regarded as a victim of the War on Terror. I know him as somebody who wanted to be devout but intelligent, thoughtful, spiritual and do everything for the right reasons. I believe he was always utterly well intentioned - as I was in my extremist days.

"I'm actually very sure that Babar would understand the very strong theological argument from within Islam against terrorism.

"I hope firmly that Babar will be able to come back to Britain soon and actually show that he is not a terrorist, or if he ever was that he no longer is a terrorist and has renounced any such views.

"He can help in peace and reconciliation - in guiding the next generation of British Muslims in a positive direction, just as IRA terrorists have done that - served their time in prison and realised that violence is not the ultimate path."

Sentencing Ahmad, Judge Janet Hall said there was no evidence he supported al-Qaeda or that he had knowledge of the 11 September plot. But she also told him: "You can't walk away from the fact that what you were doing was enabling bin Laden to be protected in Afghanistan and to train the men who actually boarded the flights that drove into the Pentagon and World Trade Centre."

Internet Jihadi: Babar Ahmad will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4's The Report on 17 July at 20:00 BST or listen again on iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.