A country where liberal journalists risk death

- Published

The life of a liberal journalist in Pakistan is not an easy one. Write about someone fighting a blasphemy case, or someone whose faith is considered heresy, and you may very soon find yourself in deep trouble.

Shoaib Adil, a 49-year-old magazine editor and publisher in Lahore, has many well-wishers and they all want him to disappear from public life or, even better, leave the country.

Since blasphemy charges were filed against him last month, the police have told him that he can't return home, he can't even be seen in the city where he grew up and worked all his life. It wouldn't be safe.

As a journalist, Adil has been a vocal critic of religious militarism. But the threat to his life doesn't come from the Taliban.

He is the victim of an everyday witch hunt by Pakistan's powerful religious groups - the kind of witch hunt that's so common and yet so scary that it never makes headlines.

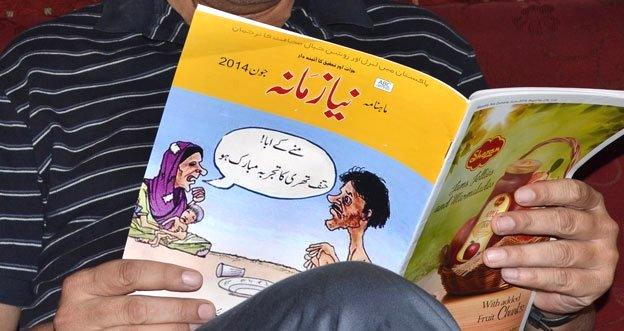

For the past 14 years, Adil has been editing and publishing a monthly current affairs magazine, a rare liberal voice in Pakistan's Urdu media. Back issues of Nia Zamana read like a catalogue of human rights abuses.

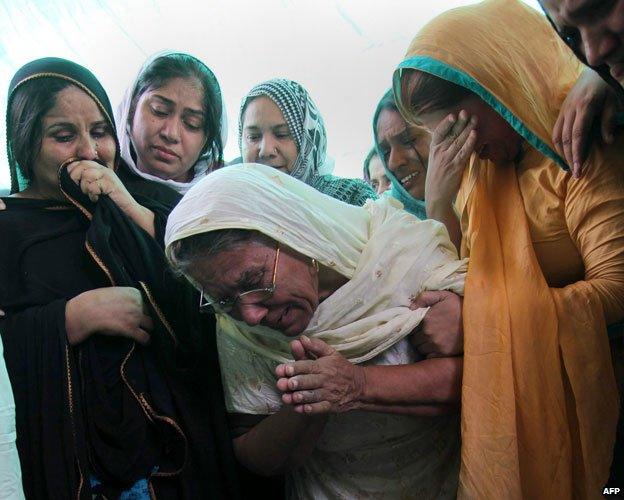

The June issue's cover story, for example, reports on the murder of a human rights lawyer, Rashid Rehman in the city of Multan in central Pakistan. Rehman, defending a literature professor accused of blasphemy, was told in the court by the prosecuting lawyers that if he didn't drop the case he would not live to see the next hearing.

Sure enough, Rehman was gunned down in his office before the next hearing.

Mourners grieving over the coffin of Rashid Rehman, murdered in May this year

Adil had just published this issue of Nia Zamana when his crusading journalistic enterprise came to an abrupt end - and he was lucky to avoid sharing Rehman's fate himself.

He was sitting in his Lahore office when a contingent of police arrived with a dozen religious activists, people Adil simply calls maulvis - teachers of Islamic law. They waved a book at him that he had published seven years ago - an autobiography of a Lahore High Court judge, titled My Journey to the Higher Court. The author, Justice Mohammed Islam Bhatti, had written that he belonged to the Ahmedi faith - a former Muslim sect that was declared non-Muslim in Pakistan exactly 40 years ago, and whose members have since then been prosecuted by the state and hounded by religious groups with equal gusto. He had then gone on to say some complimentary things about the founder of the faith.

"The maulvis ransacked my office looking for more copies of the book or any other material to pin blasphemy on me," says Adil. Police officers meanwhile explained that the group the activists belong to, the International Council for the Defence of Finality of Prophethood, had demanded the registration of a blasphemy case against him.

Adil, in hiding, reads the last issue of Nia Zamana

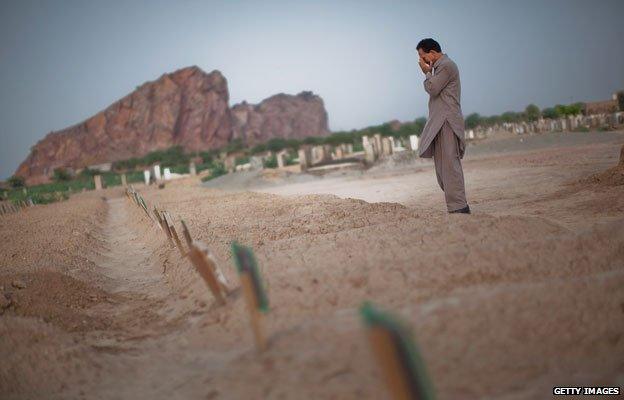

The Council is a much feared entity. Its sole purpose is to hunt down Ahmedis in Pakistan and to look for suspected sympathisers. They don't have to work very hard. The laws against Ahmedis are such that there is almost nothing that they cannot be accused of. They have been imprisoned for saying a casual Muslim greeting like "Asslamu aliakum", for printing a verse of the Koran on a wedding invitation, for calling their prayer a namaz and for calling their mosque a mosque. In Pakistan if you want to tarnish anyone in public life all you have to do is to insinuate that they are Ahmedi. Or an Ahmedi sympathiser.

"I, the complainant work as a preacher for the Finality of the Prophethood," reads the application for a blasphemy case to be registered against Adil. "I bought and read a book called Journey to Higher Judiciary, an autobiography of Mohammed Islam Bhatti, published by Mohammed Shoaib Adil. I discovered that in many parts of the book serious blasphemy has been committed against various prophets, particularly against Jesus Christ, and the prophet Mohammed. Besides that, the cursed Mirza Ghulam Ahmed Qadiani (founder of the Ahmedi sect) has been shown sitting alongside our Prophet Mohammed. The whole book is full of such blatant blasphemies."

The complaint goes on: "Because this book has hurt the religious feelings of all Muslims… the complainant pleads that the strictest action be taken against the accused."

Attacks on two Ahmedi mosques in Lahore in 2010 resulted in 93 deaths

As soon as Adil saw the book being waved in front of him, and as soon as he heard the word "blasphemy", like many others before him, he knew that life as he had known it was over.

He was taken to a police station and while he waited for his fate to be decided the Council activists stood outside making sure that the police didn't let him go. Adil managed to make some phone calls. First he called an uncle, a right-wing newspaper editor who "knows these kind of people". He called up a nephew, an influential TV reporter whose calls everyone returns. He called up the head of a journalists' collective, an influential Urdu columnist, a human rights activist. All these people started to call other people and thanks to their support the police backed down and decided not to register a case against Adil. His late father had been a well-known religious scholar, and his name was invoked again and again to plead Adil's innocence.

The police asked him to stay in the police station as the activists were still surrounding it. When they finally dispersed at 04:00 in the morning, police whisked him to a pre-designated place where his nephew waited with a bag of clothes, and he was put an early morning bus leaving for another city. The parting advice from the police was: "Don't even think of returning to the city, stay silent, write nothing in the press, don't squeak on social media, a word out of you and we wouldn't be able to guarantee your safety." He would only be safe, they said, if he disappeared from his own life and maintained a permanent silence.

Christian homes were burned in Lahore last year after accusations that a Christian had blasphemed

For the next few weeks he hid at a friend's house while his family found shelter with other relatives. Adil meanwhile sought advice from other influential friends.

The country's top human rights campaigner advised him to stay invisible, adding: "When you come to see me I feel scared for both of us." A powerful senator advised him to leave the country and promised to help him get a visa.

Adil still hoped that there might be a way of getting the blasphemy application against him squashed. Justice Bhatti, the author of the autobiography, called fellow judges in the Lahore High Court but there was no response. Then he found a friend who was on good terms with a very influential religious scholar, no less a figure than the chairman of the Council of Islamic Scholars. As it turned out the blasphemy campaign against Adil was headed by the chairman's younger brother. He listened to Adil's plea patiently and then said: "Sorry, I can't help you. My brother is so radical that he considers me an infidel."

As Adil waits for the Council activists to call off their hunt or for a country to provide him temporary refuge, there is still no registered case against him. But the police who may one day register this case, the lawyers who would then defend him, the judges who would hear the case, and every single one of Adil's journalist and activist friends have told him that if he tries to resume his former life there is no reasonable chance of his survival.

Over the past few months Pakistan has become an increasingly harsh environment for journalists, particularly those considered liberal. In Lahore a TV presenter and writer, Raza Rumi, survived an attack in March. His driver didn't. Now Rumi lives somewhere abroad and is not likely to return to Pakistan for the foreseeable future.

Hamid Mir, who is still recovering, under heavy security

Pakistan's most famous TV journalist, Hamid Mir, took six bullets in April and remains off air and under guard after returning from treatment abroad. And the country's most famous TV host, Shaista Wahdi, had to flee the country overnight after she was accused of having shown disrespect towards the prophet's family by playing a wedding song in her morning TV show.

So Shoaib Adil's well-wishers are not exaggerating the threat to his life.

Nobody has given him any advice about the magazine that is his life's work, Nia Zamana, because everyone knows that even going near that office is like inviting death. Police have told him repeatedly that his tormentors have reconnaissance teams - they will find anyone who hangs around there.

"I had only one full-time assistant, I have asked him to stay home, never mention that he was associated with me and try and find a new job," says Adil.

Although Nia Zamana had a small print run, what made it significant was that it published in Urdu, where liberal voices are now rare.

After a series of interviews during which Adil was not sure whether he should tell his story, and wasn't sure whether his well-wishers should be named or not, he made a request.

"Is it possible that you write this in English because if it comes out in Urdu and those people read it they'll be even angrier."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.