The French spy who wrote The Planet of the Apes

- Published

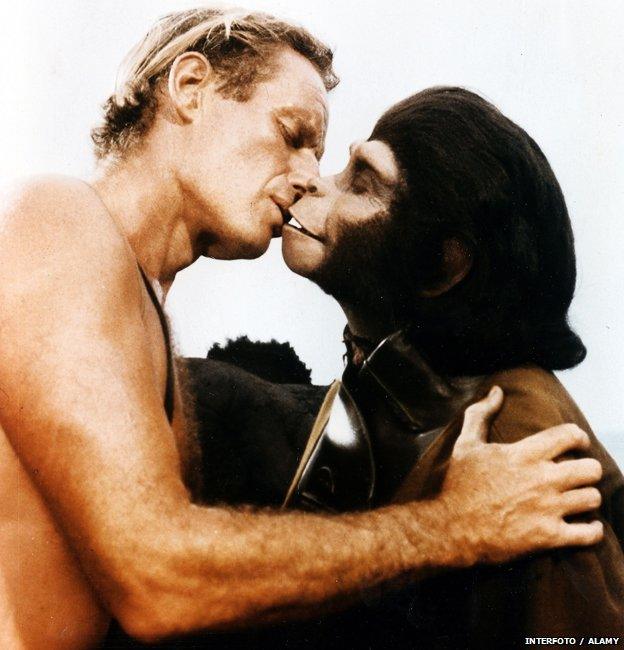

Before the newly released Dawn of the Planet of the Apes film, there was a long franchise going back to the first Apes movie - the 1968 classic with Charlton Heston. But before that there was the book.

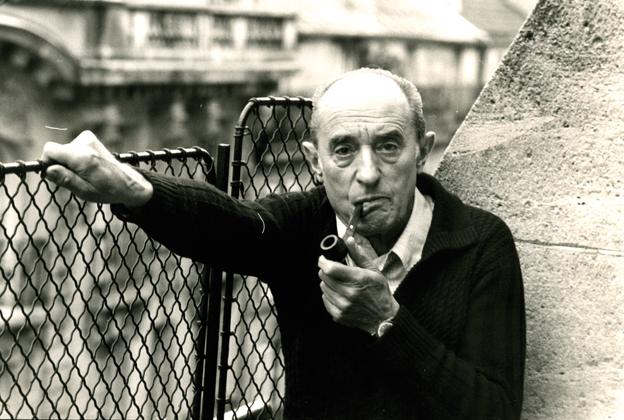

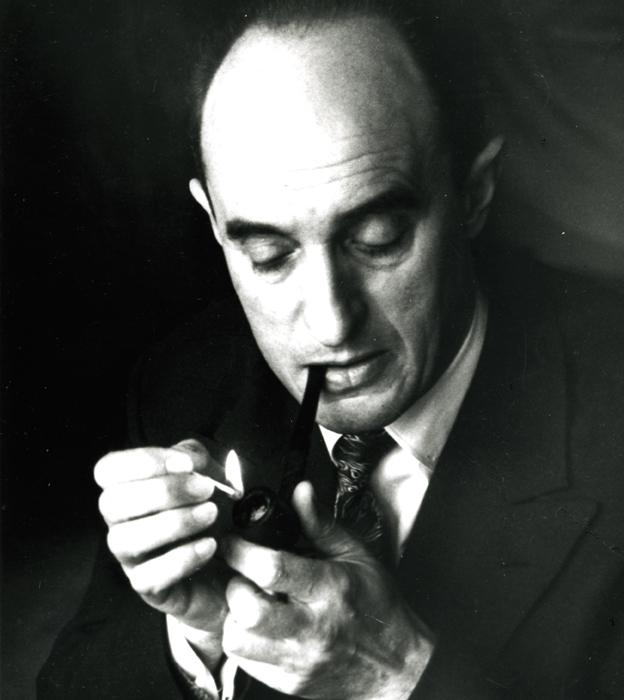

Today few people have heard of Pierre Boulle. He was the French author who first had the brilliant idea of humans travelling in time and stumbling on ape civilisation. It was in his 1963 novel La Planete des Singes (Planet of the Apes).

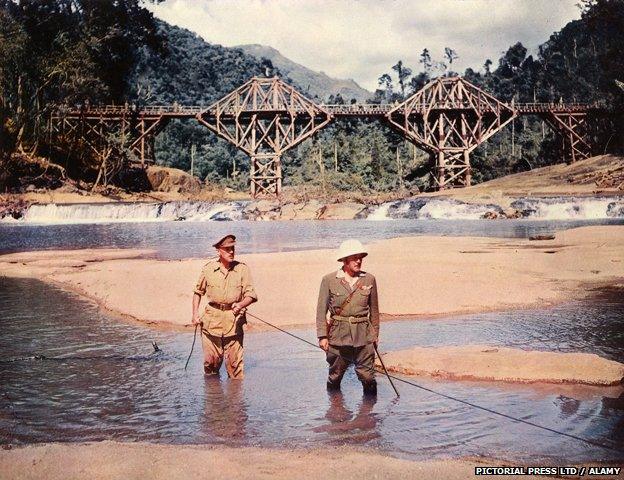

But there's more. It turns out that Pierre Boulle was also the man behind another cinema great - none other than The Bridge on the River Kwai. A book on the face of it so quintessentially British - about a British colonel and his conception of duty and honour. How on earth could it have been written by a Frenchman? And how did that same Frenchman then move from wartime adventure to the world of science fiction for his second Hollywood triumph?

Pierre Boulle died in Paris in 1994, after a writing career that spanned more than 40 years and resulted in some 30 novels and collections of short stories.

But it was his life before taking up the pen that shaped his literary outlook. From the mid-1930s he was a rubber planter for a British company in Malaysia. And in World War Two he served as an undercover agent for the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

For The Bridge on the River Kwai he was writing of a world he knew well.

"Pierre Boulle was profoundly Anglophile," says Jean Loriot, who heads the Association of Friends of Pierre Boulle.

"In the Far East he worked alongside English people. He was impregnated by English culture. He admired the English greatly. And when he came to write he made many of his heroes English."

The Bridge on the River Kwai was Boulle's third novel. The first two - William Conrad, and The Malay Spell - were named in deliberate homage to his two literary inspirations: Joseph Conrad and Somerset Maugham.

For this third book, Boulle wanted to explore the psychology of the ultra-correct Col Nicholson (played by Alec Guinness in the film), but also to raise questions about the relative value systems of the Japanese and British minds.

The opening words are: "Maybe the unbridgeable gulf that some see separating the western and the oriental souls are nothing more than a mirage?... Maybe the need to 'save face' was, in this war, as vital, as imperative, for the British as it was for the Japanese."

Much later, Boulle wrote a short autobiography called The Sources of the River Kwai in which he described his own experience in the war.

In Singapore in 1941 he signed up to the Free French, and was seconded to what became known as Force 136. This was the British SOE operation in South East Asia.

At the time, Singapore was the major British base in South East Asia

At a place called The Convent, he was put through a training course in which "serious gentlemen taught us the art of blowing up a bridge, attaching explosives to the side of a ship, derailing a train, as well as that of despatching to the next world - as silently as possible - a night-time guard".

After various missions in Burma and China, Boulle - now with the English covername Peter John Rule - was told to make his way by river to Hanoi, in Vichy-controlled Indochina.

With help from villagers he built a raft from bamboo and floated downstream. At a place called Laichau he was spotted and brought to the local French commander. Deciding on the spur of the moment to come clean, he told the commander he was from the Free French with instructions to make contact with sympathetic Vichy officials.

Unfortunately the commander was not one of them. Boulle was sentenced to forced labour for life. He spent the next two years in jail in Hanoi before escaping near the end of the war.

"The experience was seminal for Boulle," says Loriot. "When he came to Indochina he thought he was on the good side. But then a Frenchman arrested him and said, "No you are not."

"It drove home a point about the relativity of good and evil, which is the theme of all his works. What is good is good only in a certain context. Not necessarily universally."

The Bridge on the River Kwai is also noteworthy for having a different ending from the film. In the book, the bridge is not blown up. It survives as a monument to Col Nicholson's doggedness. It was the Americans in Hollywood who insisted on a more dramatic - and uplifting - end.

Boulle did not make much of a fuss over the change to his book. He was a youngish writer, happy to get the royalties. Several years later it happened again with The Planet of the Apes.

In Boulle's original book the story is told by two honeymooners holidaying in space, who find a bottle containing a manuscript. It is by a French journalist who tells of his adventures on a planet run by monkeys, where the humans are the dumb animals.

At the end of the account, the journalist arrives back at Orly airport in Paris where he finds the staff... are apes. And there is a kicker when we discover the two honeymooners are themselves chimpanzees.

The one moment the book does not contain is possibly the most memorable point of the film - the discovery at the end of the half-buried Statue of Liberty.

In the film, this communicates the astounding fact that the travellers have fast-forwarded in time, and that they are back on Earth - an Earth devastated by nuclear war, in which the apes have emerged as the new dominant species.

In Boulle's book, the events take place not on Earth but on a distant planet. (In fact the 2001 film remake by Tim Burton was closer to the book's plot.)

"It is a big difference. In the film there is this sense of human responsibility. It is man that has led to the destruction of the planet," says Clement Pieyre, who catalogued Boulle's manuscripts at the French National Library.

"But the book is more a reflection on how all civilisations are doomed to die. There has been no human fault. It is just that the return to savagery will come about anyway. Everything perishes," he says.

Boulle's work divides pretty neatly into two genres - the wartime stories and the science fiction.

"I think the link between the two types is that in each of them Boulle puts his heroes in situations of discomfort and sees how they cope. He pushes them to extremes," says Pieyre.

Boulle writes in simple French, and his books are made easier to read by a strong narrative flow (generally not a strength among modern French writers).

He was a scientist by training. According to Loriot, there is a "remorseless logic to his stories. In fact he wrote the concluding page first and then worked backwards to construct the way to that conclusion."

After the war, Boulle had an "epiphany", according to Loriot, and dedicated the rest of his life to writing. He came to Paris, where he lived with his beloved sister and niece. Loriot is the widowed husband of Boulle's niece.

When Boulle died, Loriot and his wife took possession of a trunk full of Boulle's manuscripts. Among these is a document whose existence was revealed only this week - the original French version of Boulle's screenplay for a follow-up to the 1968 film.

Such was the success of the Charlton Heston film, that Twentieth Century Fox immediately asked for a sequel.

Boulle set to the task (incorporating the Statue of Liberty ending of the first film, ironically), but his script proved unusable.

"By general admission Boulle was an amazingly imaginative writer, but he did not understand cinema," says Pieyre.

Today Boulle is almost forgotten, even in his native France. In his lifetime he was a retiring figure, shunning the literary world. He never married.

"I think part of the problem is that the French don't know how to categorise him. Some people think he's too 'Hollywood' because of the two films. But no. He was rooted in France," says Pieyre.

Loriot has dedicated the last 20 years of his life perpetuating the memory of a man he loved.

"On his deathbed, his last words to me and my wife were: 'I hope they will not forget me,'" Loriot says.

The man behind two of the greatest films of all time - plus so much else - certainly deserves better.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.