Great Art? The graffiti of the New York subway

- Published

Graffiti artists like Coco, Flint and Riff were the bane of the subway system

Forty years ago author Norman Mailer published an essay in which he declared the graffiti of the New York subway to be "The Great Art of the 70s". But what happened to the artists and why is there no subway graffiti any more?

"It started with someone just writing their name - someone saw that, and added on to it," recalls New York graffiti artist Nicer, born Hector Nazario.

"Letters going in front of letters, coming back through a letter, behind a letter, going across a letter... the subways became our playground," adds Riff170.

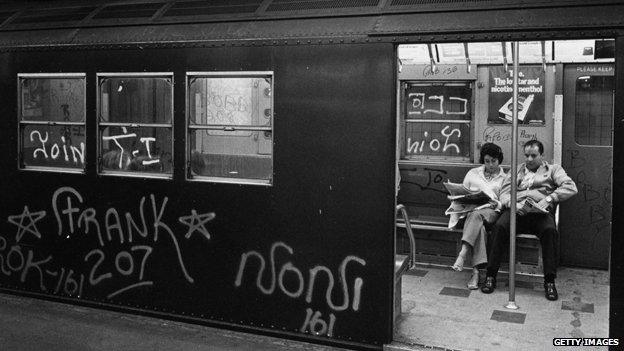

New York in 1974 was a city in crisis.

The Mayor, Abe Beame, slashed the city's budget in a bid to stave off bankruptcy, which meant laying off school teachers, police officers and subway staff.

"They was taking the money from the schools, there was a lot of corruption here, in this community, and so they took the after-school programmes away, and there was no outlets for this. So the outlet became our city," says Bronx-born designer Eric Orr, external. "And for the artist guys, those type of creative guys, it became the paint, the aerosol and the marker."

"It was like an explosion. The graffiti explosion. All of a sudden it took over the whole city. I don't know what happened, but overnight in the early 70s it was from no graffiti to all graffiti," says another former artist, Flint Gennari.

Eric Felisbret, author and former graffiti artist, says graffiti culture was in a way a product of the civil rights movement. "It was never political," he says, "but many people were brought up with that, and to express yourself by breaking the law became a natural process for them."

The graffiti pioneers came from all races, however.

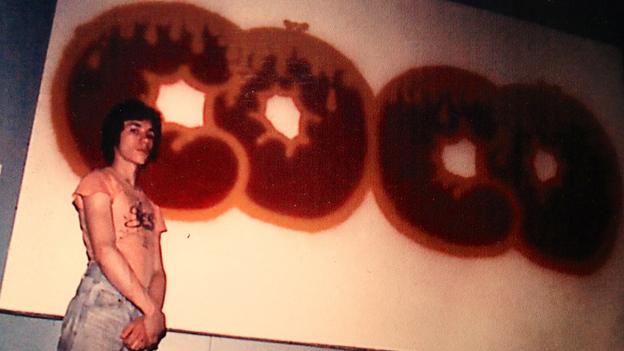

"There were writers that were African American, Latino - Puerto Rico, Dominican, Cuban - Jewish, Asian, and it became one unit - one family," says another graffiti pioneer, Roberto Gualtieri, the man behind the Coco144 tag.

He recalls a great sense of camaraderie between the young men with their spray cans, as does Gennari, who describes them as a "brotherhood" of the city's anti-establishment youth.

There were also bitter rivalries, however.

"There were crews that were after me, and, you know, I would cross their names out, and then just bank on the fact that they wouldn't catch me," reminisces Jayson Edlin - aka Terror161.

"One guy from a crew that really wanted to get me wrote a death threat on a station - 'You're dead Jayson'. Within two months of writing that he made headlines for murdering two people in a drug deal gone bad. [He] did 17 years."

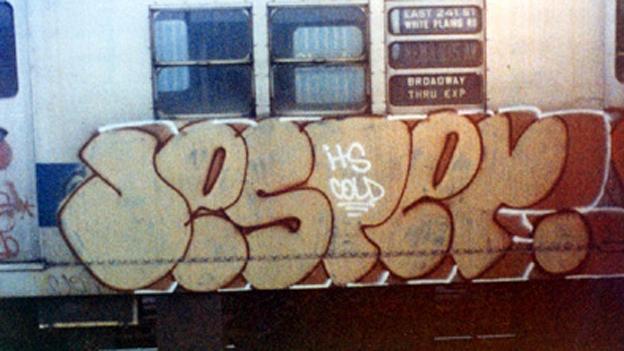

Cornell Perry, from Harlem, used the spraycan moniker Jester 1, or Dye 167

There was another threat to their lives that they diced with every night.

The mantra was "stay away from the third rail" says Cornell Perry, a graffiti writer better known as Jester1. "Just don't hit the third rail... you know the story if you hit the third rail, you'd get electrocuted, man… I mean, I stepped on the third rail many times, but I guess as I had rubber soles on, I never got electrocuted."

The third rail did claim lives though, and still does. Last month graffiti legend Jason Wulf - who used the tag DG - was electrocuted at 25th Street Station in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.

His friend, June Lang, told the New York Post, external: "He had a talent that nobody had. It was more than tagging to him. It was an art. It was beautiful. He would do side walls for businesses. He didn't just do the trains; he did everything."

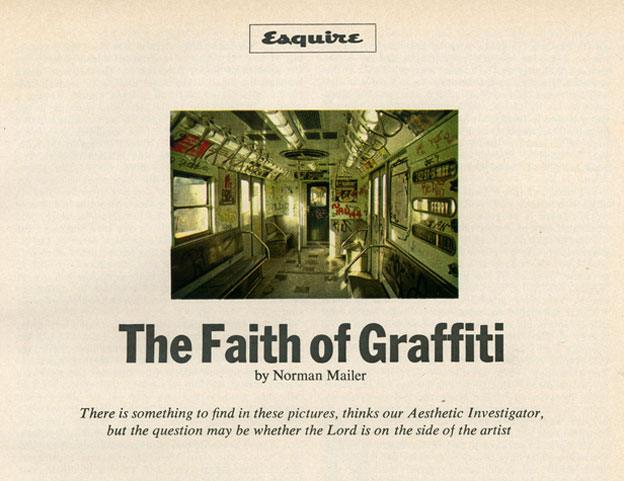

In his essay in Esquire magazine,, external Mailer wrote: "They adopt a name. It is like a logo. Moxie or Socono, Tang, Whirlpool, Duz. The kids bear a not quite definable relation to their product. It not MY NAME but THE NAME. Watching The Name Go By..."

He went on: "They had written masterpieces in letters six-feet high on the side of walls and subway cars...There was panic in the act, a species of writing with an eye over one's shoulder for the oncoming of the authority...

"There was real fear of being caught. Pain and humiliation were the implacable dues and not all graffiti artists showed equal grace under such pressure. Some wrote like cowards, timidly, furtively, jerkily. 'Man, you got messed-up handwriting,' was the condemnation of their peers."

Prof Gregory Snyder, sociologist and author of Graffiti Lives, says: "For lots of people, graffiti is ugly, vandalistic, and I'm not denying that. It's vandalism... now, oftentimes it's very clever vandalism. It can be written on a dumpster, like a garbage bin, and if someone's attempting to make a garbage bin look a little prettier maybe that's not the worst thing in the world."

But although Mailer was not alone in welcoming the flowering of creativity, the authorities hated it, as did many passengers, who felt it symbolised a city that was going to rack and ruin.

In 1977 a huge power cut led to blackouts in the city, sparking widespread looting and rioting.

Mayor Beame was turfed out of office in the wake of the debacle and was replaced by Ed Koch, who came in on a law and order ticket. Koch was determined to clean up the city and set about targeting graffiti.

"I remember in 1982 he brought everyone out to a train yard and there was a single train painted white," says former New York Daily News reporter Salvatore Arena recalls. "They were introducing a new security system, with fences and dogs. The mayor was confident it would stay white. Of course it didn't."

That same year Bob Kiley, a former CIA agent, became chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), who in 1983 hired David Gunn, as President of the NYC Transit Authority. Gunn launched a new campaign to banish graffiti - and this time it worked.

Nowadays Roberto Gualtieri, who started out as tagger Coco144, is a professional artist known as Coco

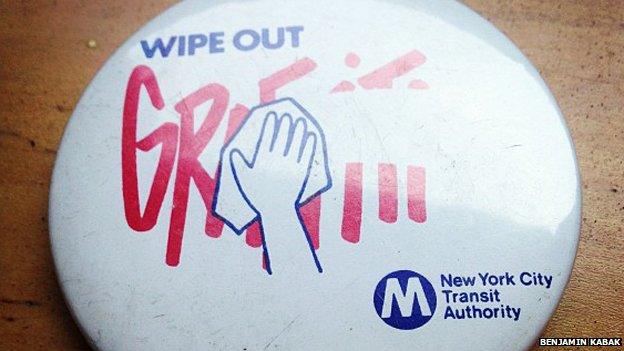

Trains were taken out of service and cleaned as soon as graffiti was spotted. Carriages were protected at night behind razor wire and the city agreed to ban the sale of spray cans to minors.

Benjamin Kabak, who writes a blog in New York,, external says the tipping point was the shooting by Bernard Goetz of four people on the subway in 1984.

"There was this sense of lawlessness underground. He shot people who were allegedly trying to mug him. I was only a child at the time but I remember the whole atmosphere - trains were covered in graffiti and stations were dark and it didn't feel safe to be underground," he says.

The mood changed. Mailer's celebration of graffiti began to feel out of date.

Throughout the 1980s the MTA worked hard to rid the system of graffiti

If in 1984 80% of subway carriages contained graffiti by May 1989 the MTA was celebrating the network being, external graffiti-free.

The change was reflected in the falling number of graffiti-related arrests - 2,400 in 1984, and only 300 in 1987.

But Prof Snyder is keen to repudiate the idea that subway users always hated graffiti.

"There was an opportunity to utilise these young people's artistic energy in the service of NYC culture," he says. "And one of the outgrowths of the graffiti movement is that people all over the world came to New York seeking NYC culture - and part of that culture they were seeking was the graffiti written on our subways."

The men behind Coco144, Jester1, Riff170 and Terror161 "retired" from the graffiti game in the 1980s but some, like Coco, went on to become professional artists.

"Graffiti has gone through an evolution, and it will continue to evolve. It's now socially accepted in places where 20, 30 years ago that would have been impossible. It's now showcased in certain museums - and let's say in another 30 years from now it may be hanging in the White House," says Nicer.

Graffiti has been replaced on New York subway trains by what is known as scratchiti

Nowadays painted graffiti is largely gone from the New York subway trains themselves and is seen instead on the walls and tunnels of the city.

It has been replaced by scratchiti, external - tags which are etched on to carriage windows using keys, knives, emery boards or chunks of lava.

Unlike the vivid images of 40 years ago, these ghostly patterns are somehow easy to ignore. Graffiti has faded quietly into the background.

Graffiti: Kings On a Mission was broadcast on Radio 4 on Thursday 7 August. Listen to the programme on the BBC iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published19 November 2013

- Published7 August 2013

- Published1 August 2014