Should anti-tattoo discrimination be illegal?

- Published

Tattoos are more popular than ever, but workers can be dismissed from or denied jobs because of their body modifications. Some want protection under employment law. Should they get it?

You're perfect for the job. You have all the skills and experience the company is looking for, and you've turned up for the interview in your smartest attire.

But there's a problem.

If you have a tattoo that incurs the displeasure of the boss, you might find any offer of employment is swiftly rescinded.

In July Jo Perkins, a consultant in Milton Keynes, had her contract terminated, external because a 4cm image of a butterfly on her foot contravened the no-visible-inking policy of the firm for which she worked. The company said she had failed to cover it up.

She wasn't the first. A 39-year-old mother-of-three from Yorkshire with the mantra "Everything happens for a reason" on her forearm was dismissed, external as a waitress in 2013 following complaints from customers. The previous year, a Next employee complained, external he had been forced from his job because his employers disliked his 80 tattoos.

In all cases, the employers insisted they were acting within their legal rights. And therein lies a potential hazard for a rapidly-growing section of the workforce.

One in five Britons now has a tattoo, according to research cited by the British Association of Dermatologists in 2012. Among US thirtysomethings the estimate, external rises to two-fifths.

From the prime minister's wife, Samantha Cameron - who has a dolphin image on her ankle - to celebrities like David Beckham and Cheryl Cole, tattooed individuals are firmly part of the mainstream.

Samantha Cameron's dolphin tattoo on her ankle

But employers have not all kept pace with changes in attitudes. A report last year for the British Sociological Association found managers frequently expressed negative views about the image projected by noticeably tattooed staff.

While ink was an asset in some industries, such as those targeting young people, most of those interviewed felt there was a "stigma" attached to visible markings, according to Andrew Timming of St Andrews University, who carried out the study.

Words like "untidy", "repugnant" and "unsavoury" were all used to describe the perception clients were likely to gain of the organisation if someone decorated in this way was hired.

This was true even when managers were themselves fond of body modifications. "There were recruiters who had tattoos, who showed me them - they weren't visible on the hand, neck or face - they wouldn't have someone with a visible tattoo on display," says Timming.

Some enthusiasts for skin markings insist this is deeply unfair. A number of e-petitions, external have been organised against tattoo-related discrimination.

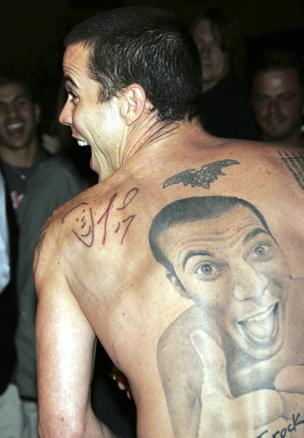

A 34-year-old from Birmingham who changed his name by deed poll to King of Ink Land King Body Art The Extreme Ink-Ite (previously Mathew Whelan), who describes himself as the UK's most tattooed man, has led a campaign to protect the employment status of people with body modifications.

The before and after shots of Body Art, formerly known as Mathew Whelan

Body Art (as he gives his shortened name), a property entrepreneur and Liberal Democrat activist in Birmingham, has personally lobbied ministers Lynne Featherstone, Jo Swinson and Ed Davey in favour of a level playing field for those with tattoos.

"If someone can do a job, they should be equal with the next person who has the same CV," he says.

Tattoos are more than simply a lifestyle choice, he argues - they are an expression of someone's identity just as much as their religion or other beliefs.

"I was nine when I knew I wanted them," he says. "People who are modified have an identity because of their image and who they are."

It's not a view that is widely shared by bosses.

Policies which restrict tattoos are commonplace in the UK. The Metropolitan Police bans them on the face, hands and above the collar line, as well as any which are "discriminatory, violent or intimidating". In 2012 the music retailer HMV was criticised, external for issuing guidelines instructing staff to cover up their ink. Airlines frequently place restrictions on tattoos, external among cabin crew.

Firms have every right to decide who represents them, argues independent human resources consultant Sandra Beale. An organisation that wishes to project a smart, professional image, or whose clients would likely be put off, is entitled to ban or limit body modifications, she says - workers can choose whether they prefer having a tattoo or a job.

Some jobs may be less strict than others

"For an employer, if they employ them in a customer-facing role, it could have an impact on reputation and doesn't portray a good corporate image," she says.

Around the world, the law tends not to protect tattooed employees.

In Japan, where tattoos are widely associated with organised crime, bans are commonplace. A US federal appeals court ruled in 2006, external that ordering public employees to cover up their tattoos did not violate their First Amendment rights. In New Zealand, where tattoos are an important part of Maori culture, a ban by the national airline on visible markings ignited a national debate. , external

However, in Victoria, Australia, they may be considered a physical feature protected by the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, according to at least one legal opinion., external

Under UK law it's perfectly legal for managers to refuse to hire someone on this basis, according to employment law expert Helen Burgess, a partner at law firm Shoosmiths. The only exception might be under the 2010 Equality Act, external if the tattoo were connected to their religion or beliefs, she says - and even then a plaintiff would have to demonstrate this were the case.

Existing employees would fare little better if their boss took a dislike to a new adornment. "If there was a blanket ban on tattoos and an individual were to turn up with one, if the employer followed proper process that would be a fair dismissal in law," Burgess says.

By contrast, Body Art argues that body modification has "protected characteristic" status under the 2010 act, given the practice's connection to people's beliefs.

Japan's tattoo taboos

Models show off the Yakuza-style body art of renowned tattoo artist Horiyoshi III

Tattooing in Japan goes at least as far back as 5,000 BC

During 7th and 8th Century, evidence suggests that tattooing began to be used as a form of punishment for criminals

Resulted in an enduring association with criminality, although elaborate tattoo artistry also has a long history

Regularly linked to Japanese mafia - known as the Yakuza - whose members often sport tattoo "suits", invisible when fully clothed

In 2012 the mayor of Osaka tried to crackdown on city workers with tattoos. "If they insist on having tattoos, they had better leave the city office and go to the private sector," he said at the time

Young people tend to be more open to tattoos but still common for visible art to be banned in gyms, water parks and many workplaces

But the fact so many organisations have anti-tattoo policies suggests this interpretation of the law has not yet entered the mainstream among HR and legal circles. Secondary legislation specifically excluded tattoos and piercings, external from the 2010 act's definition of a severe disfigurement, on which basis an employer cannot discriminate.

For this reason, some tattoo artists refuse to ink the face, neck or hands of customers who are not already heavily inked.

Nonetheless, the sheer critical mass of younger people with tattoos suggests it's likely that attitudes are likely to change over time regardless of what the law says.

Employers - especially those seeking specialist skills - may find they can't afford to exclude talent. In an effort to tackle a recruitment shortfall, the British Army is reported to be considering relaxing its rules to allow tattoos on the face, neck and hands.

However, says Timming, "There will be certain genres of tattoos that would never be normalised. Any kind of racist symbols would be a death sentence in terms of your job prospects."

Even now, he says, the size and location of a tattoo make a big difference to whether an employer is likely to accept it.

Likewise, designs with connotations of drugs, violence, crime or death are likely to impede a job search, Timming says. Even football-related tattoos sometimes cause applicants to be rejected because some employers associate them with hooliganism.

By contrast, "any kind of more innocuous, smaller tattoos - a rose or a butterfly - would be more acceptable in the workplace".

For the time being, it's advice worth considering when balancing the appeal of that new tattoo against the prospect of a dream job.

Readers share their experiences of losing out in the jobs market because of their tattoos.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.