The makeover that's divided a nation

- Published

Macedonia has embarked on a major revamp of its capital city, Skopje. But the changes have been controversial with some calling the makeover a "crime".

Skopje may not be the highest profile European capital. Indeed, until 1991 it was not a capital at all - but just a large provincial city in what used to be Yugoslavia.

But now, as Macedonia's seat of government, it is trying to make a name for itself - and stirring up its citizens in the process. Skopje is using the time-honoured tactic of eye-catching architecture - but in a much more radical way than other European cities which have gone down that road.

In Spain, Bilbao used the Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Museum to attract tourism and investment. When it opened in 1997, the building's radical, abstract curves completely changed the city's profile.

Meanwhile, Liverpool's status as European Capital of Culture in 2008 allowed it to highlight its many beautiful neoclassical buildings. Skopje's strategy is a combination of the two approaches - taken to the extreme.

The project is known as Skopje 2014 - but for inspiration it looks to a distant epoch. As Macedonia scrabbled around for identity in the wake of Yugoslavia's disintegration, a group of historians, architects and politicians decided that the country should remind itself - and the world - of a proud past.

This was the background to the staggering frenzy of building and sculpting which has consumed Skopje over the past few years.

The project, instigated by prime minister Nikola Gruevski, officially started four years ago, and has proceeded at breath-taking speed.

In April last year, the government said it had spent 200m euros ($264m; £159m) on the work - the original estimate was 80m euros ($106m; £64m) and critics have suggested the true cost could be anything up to a billion euros ($1.3bn; £795m).

The banks of the Vardar River, which runs through the city centre, now boast new museums, government buildings and a reconstructed National Theatre. All of them have been built in a style its proponents label either neoclassical or baroque, in striking contrast to the modernist character of most of Skopje.

Then there are the statues. Dozens of bronze-cast figures have sprouted up seemingly everywhere. Just on the newly-constructed Art Bridge across the Vardar, there are no fewer than 29 of them, representing significant Macedonian figures in music, literature and visual arts.

Elsewhere in the city, everyone from the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great to Mother Teresa has a monument to remind visitors and residents alike that though Macedonia may be small, it has produced great people.

But the piece de resistance is in Macedonia Square. A gigantic warrior on a horse now dominates this previously empty plaza. The figure - which may or may not be Alexander the Great, depending on whom one asks - perches on top of a thick column, surrounded by lions. Music, lights and dancing fountains provide the icing on the cake.

The whole effect is certainly nothing less than eyebrow-raising. And for some people it is positively stomach-churning. But in raising the profile of the city, Skopje 2014 has achieved the desired effect.

The project is providing precisely the national identity which was previously lacking, says the current head of the Foreign Affairs Committee - and former foreign minister - Antonio Milososki.

He points to the jump in tourist arrivals as proof of its success. Government statistics suggest that overseas tourist arrivals tripled over the decade from 2002 to 2012. And Milososki says that, for once, the changes have been locally-driven.

"In different periods of history, our neighbours or empires decided on the structure, constitution, city architecture - whether they were Ottomans, Serbs, Bulgarians or other bigger states. Now for the first time since independence, we've put our stamp on our capital city."

To say this stamp is not quite to everyone's taste would be a considerable understatement.

"This is a crime against public space, culture, urbanism and art - against the city and the citizen," fumes Miroslav Grcev, professor of urban design at the Saints Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje.

As the creator of the current Macedonian flag, he is well-qualified to talk about issues of national identity. And he views Skopje 2014 as the darkest of black comedies.

Grcev is particularly aggrieved by the alterations made to some of Skopje's most prominent buildings. Baroque facades have been placed over the modernist cubes of Government House and attached to apartment and shops around the city's main square.

He is not exactly keen on the statues either, reserving particular contempt for the warrior on a horse.

"I stopped going to the centre of the city. When I have to go past those monstrous, criminal colonnades and things which are not sculpture, I walk with my head down and my eyes to my shoes - the walk of a dead man," he says.

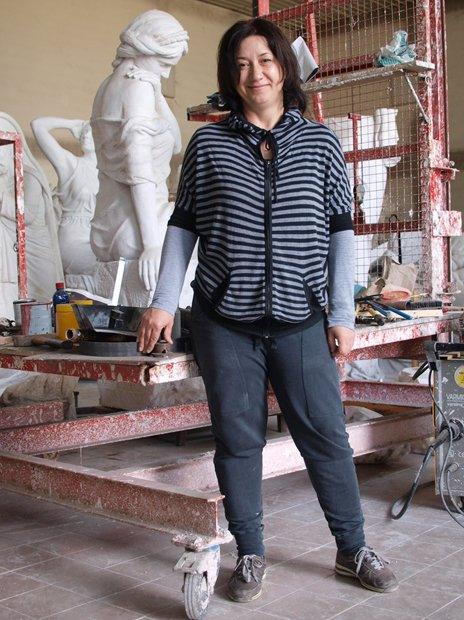

The creator of the most contentious of the statues shrugs at the fuss her work has created. Business is brisk for sculptor Valentina Stefanovska her workshop in a suburb of Skopje.

Before she won the competition to construct the centrepiece of Skopje 2014, she had barely had a professional commission. Now she's made her mark on the city - not just with the rampant warrior in the main square, but an Arc de Triomphe lookalike nearby known as Porta Macedonia.

"The centre of the city was a little bit empty before - there was too much space. People might have been against the statues before, but now they congratulate me," she says.

Skopje is no stranger to radical change. In 1963, an earthquake flattened four-fifths of the city and forced a total rebuild, overseen by Kenzo Tange, the Japanese architect and urban planner who had performed a similar duty in post-war Hiroshima.

More than 100,000 people were made homeless by the 1963 earthquake

Architecture aficionados adored the result - a masterpiece of the brutalist and metabolist schools. Mostly the lines were clean and geometric - though as a nod to Tange, the main post office opens out into an impressionistic lotus flower.

But some residents admit they found the endless raw concrete unappealing and lacking in variety. Now at least they have that in spades.

It all adds up to the most radical new look since Sandy reinvented herself at the climax of Grease. And if we can celebrate the neoclassical buildings of a city in Northern England, then why not embrace those in a country a lot closer to the original source of columns and colonnades?

Perhaps Skopje will grow into its new image. Or maybe, a few years down the line, it will take a look in the mirror and decide that it is time for another change.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published10 June 2024