Project Hieroglyph: Fighting society's dystopian future

- Published

- comments

Science fiction writers and scientists have joined together to create more optimistic views of the future

Pop culture has painted a darkly dystopian vision of the future. But a new book hopes to harness the power of science fiction to plot out a more optimistic path for the real world.

Just glancing at this week's movie listings, those in the US can see humans battling super apes for world domination, a gang of Marvel misfits fighting against the universe's certain doom, or a young boy tasked with keeping all memories of a society that has done away with individuality.

The future, according to Hollywood, doesn't look so good. Successful dystopian science fiction television shows like HBO's The Leftovers and books like The Hunger Games trilogy add to the notion that bad news is very much in store.

Acclaimed science-fiction writer Neal Stephenson saw this bleak trend in his own work, but didn't give it much thought until he attended a conference on the future a couple years ago.

At the time, Stephenson said that science fiction guides innovation because young readers later grow up to be scientists and engineers.

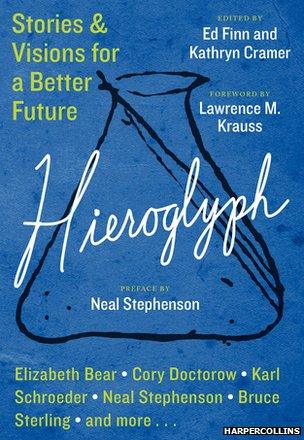

A compilation of short stories from Project Hieroglyph will be released on 9 September

But fellow attendee Michael Crow, president of Arizona State University (ASU), "took a more sort of provocative stance, that science fiction actually needed to supply ideas that scientists and engineers could actually implement", Stephenson says.

"[He] basically told me that I needed to get off my duff and start writing science fiction in a more constructive and optimistic vein."

That conversation spawned a new endeavour called Project Hieroglyph, which seeks to bring science fiction writers and scientists together to learn from, and influence, each other - and in turn, the future.

Renowned writers such as Bruce Sterling and Cory Doctorow were tasked with working with scientists to imagine optimistic, technically-grounded science fiction stories depicting futures achievable within the next 50 years.

Those stories, collected in a book also entitled Hieroglyph, will be released on 9 September.

"We want to create a more open, optimistic, ambitious and engaged conversation about the future," project director Ed Finn says.

According to his argument, negative visions of the future as perpetuated in pop culture are limiting people's abilities to dream big or think outside the box. Science fiction, he says, should do more.

"A good science fiction story can be very powerful," Finn says. "It can inspire hundreds, thousands, millions of people to rally around something that they want to do"

Hieroglyph writers' visions of the future:

Environmentalists fight to stop entrepreneurs from building the first extreme tourism destination hotel in Antarctica

People vie for citizenship on a near-zero-gravity moon of Mars, which has become a hub for innovation

Animal activists use drones to track elephant poachers

A crew crowd-funds a mission to the Moon to set up an autonomous 3D printing robot to create new building materials

A 20km tall tower spurs the US steel industry, sparks new methods of generating renewable energy and houses The First Bar in Space

Indeed, the influence of science fiction is already apparent in modern research, says Braden Allenby, Project Hieroglyph, external participant and professor of engineering, ethics and law at ASU.

"Why do we end up with the technologies we do? Why are people working on, for example, invisibility cloaks? Well, it's Harry Potter, right? That's where they saw it," he says. "Why are people interested in hand-held devices that allow you to diagnose diseases anywhere in the world? Well, that's what Mr Spock can do. Why can't we?"

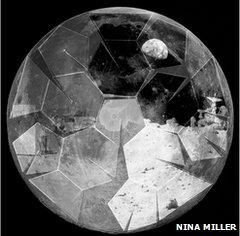

The book also features illustrations of potential technology, like this drone in the short story Johnny Appledrone Vs. the FAA

ASU structural engineer professor Keith Hjelmstad has been thinking about tall architecture throughout his nearly four-decade-long career. As a professor, he even instructed the designer of Dubai's Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world.

But it was his collaboration with Stephenson on a short science fiction story about a steel tower 20km high that really sparked his imagination.

"That [idea] caught my curiosity like almost nothing ever has before," Hjelmstad adds. "I wasn't thinking about it and now, of course, I can't stop thinking about it."

The collaboration also spawned detailed, structurally accurate 3D models of Stephenson's ideas, a "thrilling" first in his thirty-year career as a writer.

Author Neal Stephenson writes of a fictional 20km-tall tower constructed of steel

"I was seeing something that was actually based on physics," he says. "It injects a new element into the science fiction writing process that could be of benefit to writers and to readers who get to see these depictions, and also to people like [Hjelmstad] who get to reach a larger audience."

That larger audience may extend to not only other scientists and innovators, but politicians who can influence our society for generations to come.

"If the government has to decide what to fund and what not to fund, they are going to get their ideas and decisions mostly from science fiction… rather than what's being published in technical papers," says Srikanth Saripalli, an ASU roboticist and project participant.

Drones, his specialty, are frequently depicted as weapons or a means of surveillance rather than helpful tools used for search and rescue, agriculture and traffic monitoring.

Science fiction writer Lee Konstantinou worked with Saripalli on a story, Johnny Appledrone Vs. the FAA, about a future in which drones are commonplace and utilised in communication.

Konstantinou admits he was initially sceptical about the nature of Project Hieroglyph, worrying it would "white-wash negative aspects of our reality [and be] too Pollyanna-ish".

Instead, he now sees the medium as a way to spur creative thinking.

"It's not the job of the science fiction writer to create a blueprint for the future, but it's part of a collaboration with the reader to think hard about problems and to think about how people working together might overcome them."

In "Periapsis", Hieroglyph writer James L Cambias envisions people inhabiting a near-zero-gravity moon of Mars

According to Finn, his involvement in Project Hieroglyph has already changed how he sees what's next for society.

"I do feel more positive about our future," he says. Dystopianism may be having a pop-culture moment, but people are ready for something new.

"We desperately need better stories," Finn says. "If we want to have better futures, we need to have better dreams."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.