We need Miss Marple

- Published

- comments

Fighting crime is, surely, a job for us all.

Amid press and, apparently, popular outrage at the idea of the police "forcing the public to act as DIY detectives", it is, perhaps, worth asking whether that is really such a bad thing.

Is it reasonable to expect the police to investigate every alleged crime reported to them?

The notion that citizens should demand the police alone pursue and apprehend offenders has never been part of the deal. We seem to have forgotten the "historic tradition", as Sir Robert Peel described it, that the police are the public and the public are the police.

The report from the police inspectorate that prompted all the headlines about victims being asked to investigate crime actually begins with exactly that thought.

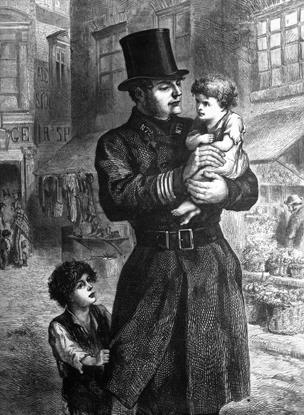

An early "Bobbie" on his beat

Paragraph 1.3 of today's HMIC report states: "In this country, for longer than records can show, citizens have had a shared and common obligation to pursue and apprehend offenders, and to bring them before a court of justice."

The HMIC itself, therefore, starts with the important observation that, far from being forced to investigate crime, it is people's duty. These days we tend to ignore that public obligation largely because, since Peel set out his principles in 1829, police forces have looked to take control of the investigative process.

They have not wanted some Miss Marple character interfering with their work. The business of investigating and dealing with crime is for badged police officers, not amateur sleuths, many detectives would passionately argue.

When it comes to crime, the public have been encouraged to see themselves as passive victims who must rely on the professionals to try to sort out their problem.

It is a decidedly un-British view, of course. The principles of our liberty and justice were founded upon an accepted community responsibility for keeping The King's Peace that has its origins in Anglo-Saxon days. People didn't look to the authorities for answers - crime was a matter for local citizens themselves.

From the 14th Century, it was the obligation and privilege of unpaid Justices of the Peace selected from the local gentry to direct the parish constables and watchmen in a system dating back to 1285 and the Statute of Winchester.

For more than 500 years, the streets and gates of walled British towns were patrolled and guarded by men from a roster of volunteers.

Every man between the ages of 15 and 60 had to keep in his house "harness to keep the peace". For men of superior rank that meant "a hauberke and helm of iron, a sword, a knife and a horse". The poor were obliged to have bows and arrows to hand.

I don't think many would suggest we return to the hauberke and helm, but the idea that each citizen has a responsibility for law and order in their neighbourhood surely has merit. We don't have a problem in encouraging people to lock their doors. Neighbourhood Watch committees are applauded for keeping an eye out for crime.

David Walliams' Sid Pegg was a tad overzealous as Little Britain's Neighbourhood Watch leader

After losing a mobile phone these days, its owner might use an app to try to track it down. Communities often organise searches, poster campaigns and Twitter appeals for missing cats, dogs and even people. Is it so crazy to suggest that someone looks to see if their neighbour's stolen vase is offered for sale at the local car boot?

I hope I wouldn't just wait for the cops to arrive if I saw a thief snatch someone's bag. We applaud those who pursue criminals as "have-a-go-heroes" - individuals who are prepared to take personal responsibility in the fight against wrong-doing.

The police have a vital role in investigating crime and anti-social behaviour. They enjoy special powers, resources and expertise specifically for this purpose - albeit that budgets are increasingly tight.

The question is whether it is legitimate for officers to say: "Look, we do not have the time or money to attend every incident. The chances of solving your crime are extremely low and, actually, we can use our resources more effectively by dealing with this over the phone. If you want to make your own inquiries and see what you can come up with, please do. If you find anything, come back to us."

The HMIC finds such a response "both surprising and a matter of material concern". The inspectors go further, arguing that "police have been given powers and resources to investigate crime by the public, and there should be no expectation on the part of the police that an inversion of that responsibility is acceptable".

But why is that unacceptable? It implies a level of passivity on the part of the public that goes against the principles of active citizenship, a statist approach on a par with people who won't pick up litter outside their house because that is the council's job.

Fighting crime, making our communities safer and more contented, is not a job just for the police. It is a job for us all.