The era of radical concrete

- Published

Stevenage was designated as the first "new town" in August 1946, during the aftermath of World War Two

A massive collection of images from British urban developments of the 1960s and 1970s now provides a treasure trove for those who want to reassess a vilified era of town planning.

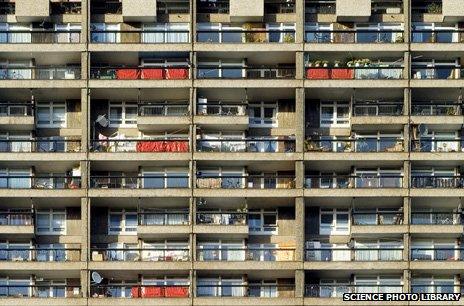

The concrete architecture that dominated Britain's post-war landscape has always provoked visceral emotions. The concrete monoliths that have survived popular culls still divide opinion, with some likening them to Orwellian dystopias.

They were part of a massive wave of development orchestrated by a generation of architects and planners who wanted to improve the way people lived.

JR "Jimmy" James, chief planner from 1961-1967

One of those heavily involved with this regeneration was JR "Jimmy" James - a "titan of post-war planning", as one former colleague put it. He helped launch the new towns of Newton Aycliffe and Peterlee in the late 1940s, eventually becoming chief planner at the Ministry of Housing and Local Government from 1961-1967.

When James died in 1980, he left behind a collection of nearly 4,000 slides, external amassed over several decades of interest in the work of planners around the UK. Many offer a glimpse into the evolution of town planning at a time when anything seemed possible.

The slides record some of the most radical buildings the UK has ever witnessed.

Thamesmead in London was billed as a "21st Century town" when it was built in the 1960s. One striking slide shows several brutalist buildings across the glistening Thames. But already by 1971 it could serve as the backdrop for the dystopian violence of Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange.

The Brunswick Centre in London had become a "rain-streaked, litter-strewn concrete monstrosity that seemed destined for the bulldozer before it was eventually redeveloped, external".

Trinity Square in Gateshead was less fortunate. Also known as the Get Carter Car Park, it was demolished in 2010 after decades of criticism.

"These were the big bold expressions of 20th Century modernism, which were certainly popular with an architectural elite and politicians on the left," says Clapson.

Architects and planners are now quick to note that their 1960s and 1970s predecessors were making genuine attempts to alleviate very real problems. Building vertically relieved pressures of overcrowding. French architect Le Corbusier's concrete structures were an inspiration to many.

Sheffield's Park Hill was based on the concept of having "streets in the sky" - the idea that milk floats could drive right up to the top floor of a block of flats.

Thamesmead, built during the 1960s on the south bank of the River Thames in London, was designed as a futuristic city

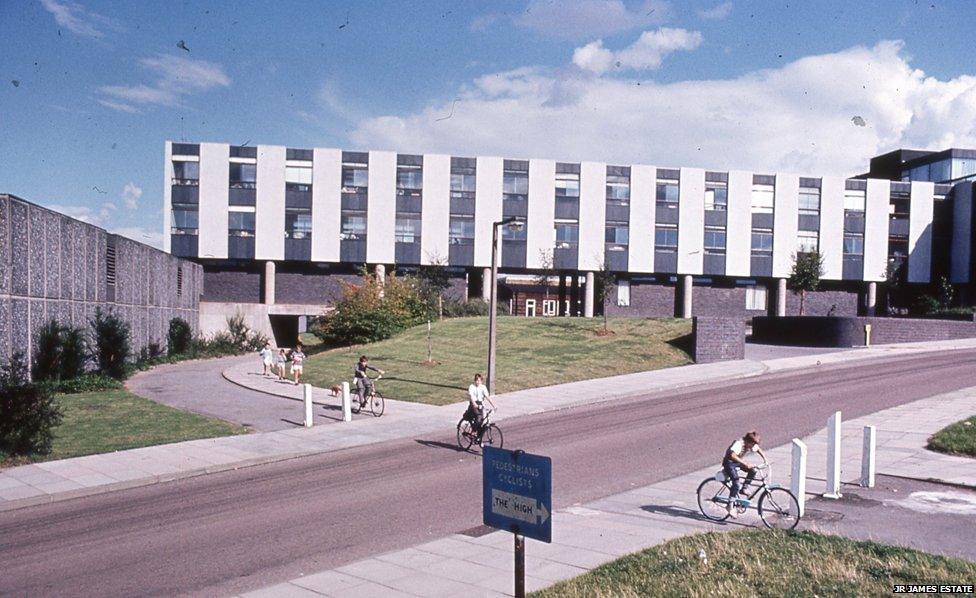

The Brunswick Centre in Bloomsbury, London, pictured here upon its completion in 1972, was widely disliked for many years but was listed in 2000

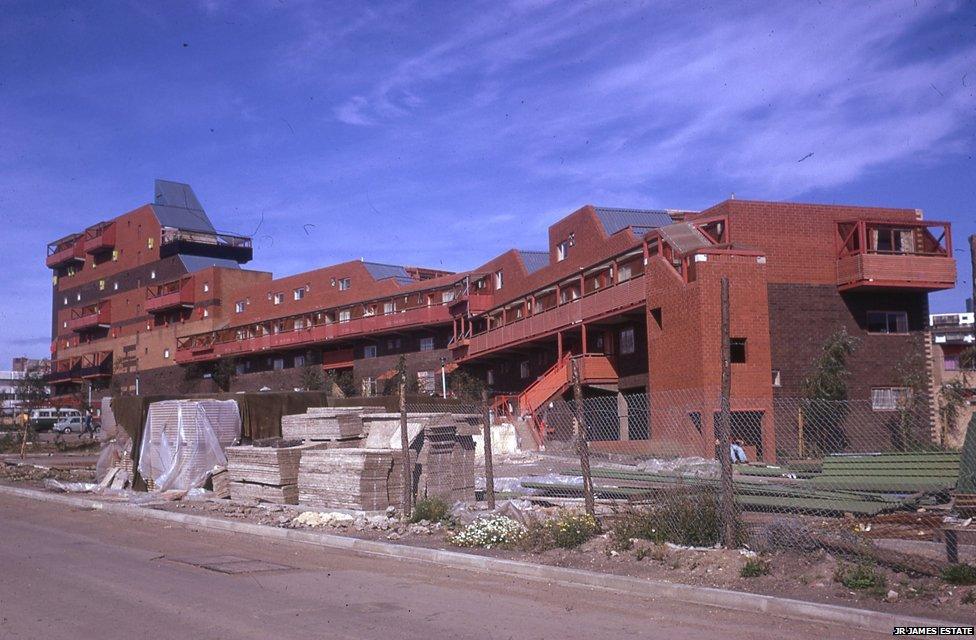

Byker Wall in Newcastle, pictured here during its construction between 1969 and 1982, was designed by Ralph Erskine

The era has led to lasting resentment.

"For many people today the planners are responsible for having destroyed a lot of post-war British towns," says Dr Mark Clapson, reader in History at University of Westminster. "They say that a lot of architectural heritage was lost for failed modern experiments. Planner was like a dirty word."

But after the devastation of World War Two, chronic housing shortages and overcrowding demanded new solutions. And the town planners were deemed to have them.

With housing shortages again firmly part of the national debate in the UK, the spirit of the 1940s has been invoked with the announcing of three new garden cities.

More than 20 designated "new towns", or garden cities, were created in the first 25 years after the war, such as Stevenage (1946) and Harlow (1947).

"The optimism for the future is something that really shines through [from the James archive]," says 23-year-old Philip Brown, who graduated from University of Sheffield's Town and Regional Planning Department, which James had helped set up and lead after leaving the civil service.

After spending some 30 years lost in a Sheffield basement, the slides were digitised by Brown and a fellow graduate late last year.

It's nice to have a glimpse into a time when town planning was automatically seen as a force for good, says Brown. "It was the idea that town planning could be a way of making our cities more liveable," he says.

The new town of Harlow, in Essex, was built in 1947 to ease overcrowding in London following the war. It incorporated a market town of the same name

Jimmy James played a leading role in getting Peterlee designated as an official "new town" in 1948

Park Hill council housing estate in Sheffield was built between 1957 and 1961. Despite social problems, the site was listed in 1998 and later redeveloped

The "streets in the sky" concept aimed at making high-rise flats accessible to milk floats and delivery vehicles, to recreate traditional face-to-face interactions

With something like the "streets in the sky" concept, the aim was to keep the "solidarity of the street and face-to-face interaction", says Prof Michael Hebbert, professor of town planning at UCL. "It didn't work, but you can understand the underlying logic of it."

"There was a sort of environmental social engineering," explains Clapson.

In retrospect they got it wrong, particularly when it came to traffic, says Hebbert. The rise of the motorcar was seen as so inevitable that dual carriageways were controversially constructed through traditional neighbourhoods.

But building up is not the only way to solve housing shortages. There's also building out.

"You had two different visions for post-war 'New Jerusalem' - one was very modernistic and the other was much more garden city-influenced," says Clapson.

So as tower blocks rose in the inner-cities, terraced or semi-detached houses grew out into new towns - Cumbernauld (1956), Skelmersdale (1961) and Milton Keynes (1967).

The two visions caused tension, says Clapson.

Jimmy James - as most planners did - favoured building outwards.

Welwyn Garden City, pictured here in 1974, is both a garden city (founded 1920) and a new town (designated 1948)

"Planners were on the whole arguing that we shouldn't go down the route of high-rise development," says Prof Tony Crook, an emeritus professor at the University of Sheffield who knew James well.

But planners were often overruled by politicians.

"So what you had was an architectural solution that reflected the political decision not to lose population to the surrounding counties," Crook explains. "Had Sheffield, for example, got a boundary extension, the high-rise blocks would probably not have been built."

Yet for all the talk of brutalist "eyesores", many developments were initially well-received, especially Sheffield's Park Hill in 1961.

"People came from all over the world to see," says Crook. "This was cutting edge architecture and people beat a path to Sheffield to be able to see it."

Many of the new inhabitants had previously been living in slums or tenements.

Many incoming inhabitants to the designated new towns came from slums or tenements, such as these in Abbotsford Place in Glasgow

"For the first time they had internal toilets and bathrooms, some quite large living rooms," Clapson says. Balconies and separate rooms for children were other new luxuries.

Only later, when the tall flats encountered social problems in the 1970s and 1980s, did the utopian dreams of the post-war planners sour. Recreating close-knit traditional communities by design in either high-rise structures or new towns miles away regularly proved difficult.

"Letting loose the lunatics wasn't the greatest of ideas, Giving them plans and money to squander should have been the worst of our fears," sings Paul Weller in 1982's The Planner's Dream Goes Wrong.

Quaint ideas of milk floats on streets in the sky morphed into a reputation for being a thief's perfect getaway.

Although Park Hill became listed, nearby Norfolk Park and Hyde Park estates were both demolished.

In later decades, Park Hill's "streets in the sky" came to be seen as dangerous and an easy escape route for petty thieves

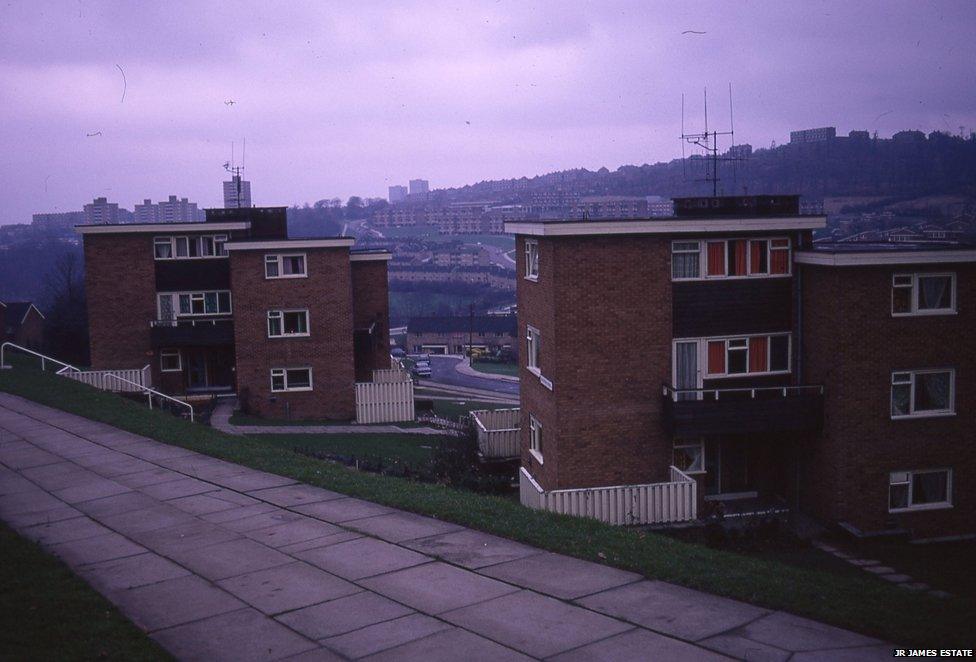

Sheffield's Norfolk Park estate was built in the 1960s, but after decline in the 1980s it was partially demolished and redeveloped from 1995 onwards

The Hyde Park estate in Sheffield, close to the Park Hill flats, was partially demolished in time for the 1991 World Student Games

Nothing sums up the erosion of an ideal quite like Sheffield's Gleadless Valley, suggests Brown.

City on the Move, a 1971 promotional video, features a narrator heralding its "showpieces of civic development", where "outworn residential areas have been replaced by modern dwellings".

"Its Mediterranean style has won international praise… the national contours of the hills skilfully exploited."

By 2008, local paper The Star questioned, external if it was the city's worst estate. Later it served as the setting for This is England '86 - hardly a beacon of British hope and prosperity.

Formerly a rural area, Gleadless Valley housing estate was built 2.5 miles from the city centre from 1955-1962, and was initially praised

Mismanagement and neglect have often been blamed for the ruination of estates. Other developments were poorly built in the first place, the critics say. Many were supposed to have lasted 60 years, says Crook.

And opinions change. Scottish new town Cumbernauld has won numerous unflattering design awards for the "megastructure" dominating the town centre.

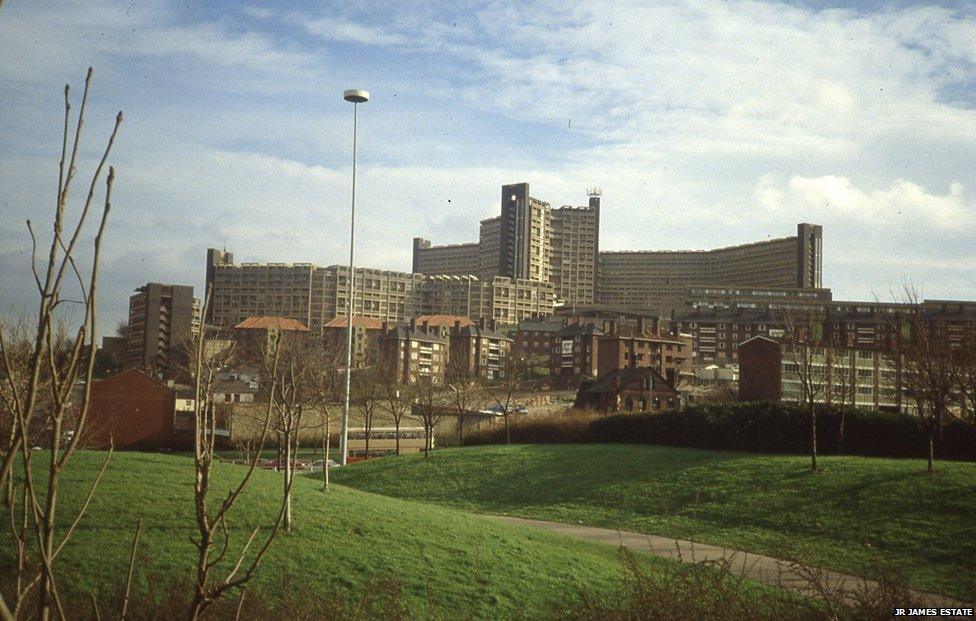

The "megastructure" in Cumbernauld's town centre, designed by Geoffrey Copcutt, has led the Scottish new town to numerous "Carbuncle" awards

But the concept of solving Glasgow's housing problems through new towns remains intact and Cumbernauld's residences are actually popular, Hebbert says.

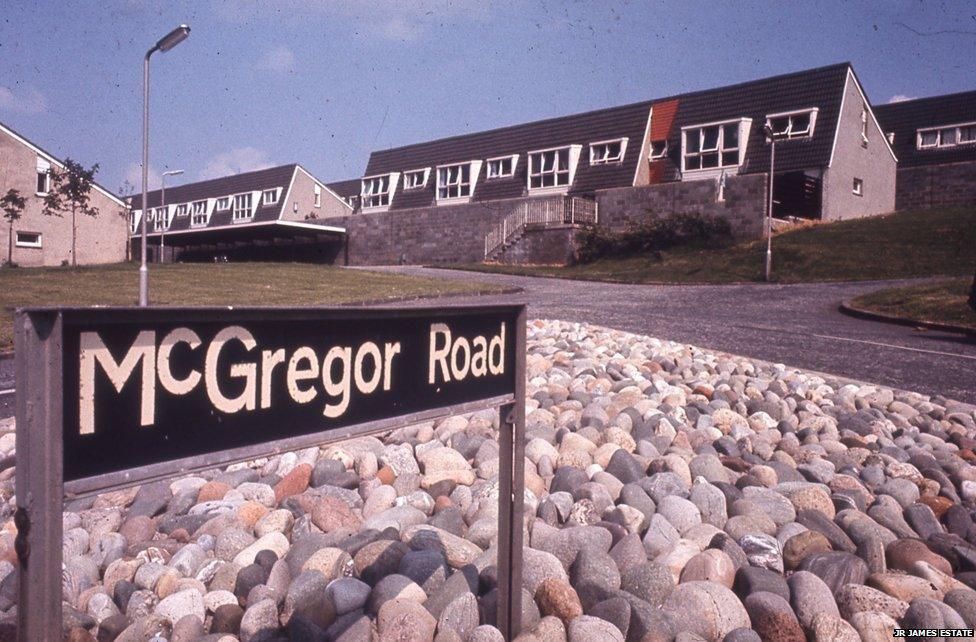

Much of the housing built in Cumbernauld and Milton Keynes at the time wouldn't look out of place among newer builds today.

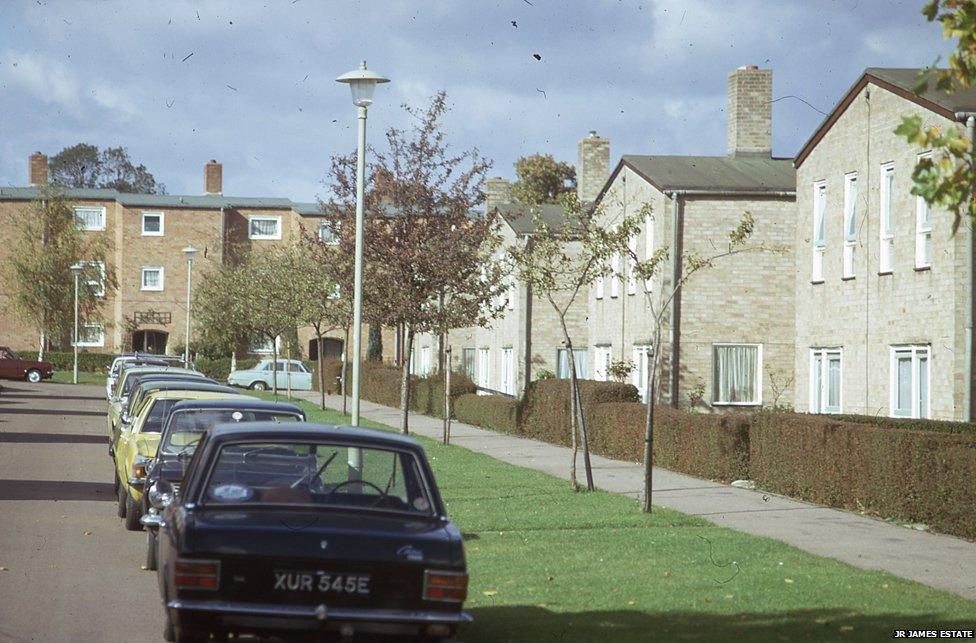

The housing in Cumbernauld, pictured here in 1967, has generally been well-received

New housing while still under construction in the new town of Milton Keynes, which was formally designated in 1967

Despite some successes, the planners bore the brunt of the backlash.

"People actually didn't like their lives being reorganised in this way," says Hebbert. It was seen as paternalistic, "a top-down manoeuvring of people's lives which the free British citizen became increasingly unhappy with".

"You kind of go from visions of utopia to critiques of subtopia," adds Clapson, citing architecture critic Ian Nairn's term for unsightly, sprawling suburban development.

"Postwar ideals had collapsed into a kind of 1950s that Britain had been like before the war."

But there's been a revival of sorts for some brutalist buildings.

Park Hill was nominated for a Stirling Prize last year after being redeveloped. "Now it's almost hipster," says Brown.

London's Trellick Tower and The Barbican are now both listed and desirable places to live.

"Increasingly [there's] a sense that modernist heritage is heritage - and needs to be respected as much as Victorian or Georgian," Hebbert says.

And for all the flak, brutalism still finds admirers among today's new town planners. "I'm not going to say that every example of brutalism is brilliant," says Brown. "But I'm not going to deny being a member of the brutalism appreciation page on Facebook either."

It also seems they've recaptured some of the optimism. Brown admits there's still some negativity towards planning, but says it's also seen as a great protector of what's there.

"You've got to be optimistic - otherwise what are you going into it for?"

Brutalism

Term originates from the French, beton "brut", which means exposed concrete

Movement characterised by functional approach towards building design

Buildings can be distinguished by their unusual shapes, rough unfinished surfaces and textures, bold geometries and massive scale

Seen in the work of Le Corbusier from the late 1940s

Movement was popular in the UK from the 1950s until early 1970s

Sources: Riba, external and Twentieth Century Society, external

Readers shared their experiences of living in 1960s tower blocks.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.