Stirling Prize: Park Hill Phase 1

- Published

It started as a thriving community for Sheffield's council tenants, but quickly descended into a sink estate. Now Park Hill is flourishing again. Should every rundown tower block get the same treatment?

It is a concrete monolith, all straight lines and sharp corners. Park Hill stands 13 storeys tall, its monochrome structure now broken up with flashes of yellow and red.

It is both loved and hated - like so many 1960s buildings. But while some have been razed to the ground, Park Hill was listed and preserved. Why?

"It's a Marmite building," says architect David Bickle.

"It is challenging. It's not obviously pretty, but it works. The more time we spent working on it the more we realised just how clever it is."

Also in the running are Astley Castle, Bishop Edward King Chapel, Giant's Causeway Visitor Centre, Newhall Be and the University of Limerick Medical School.

Park Hill, which opened in 1961, was the most ambitious inner city housing scheme of its time.

It was an example of Brutalism. Derived from the word "brut", French for raw, it is a style that is heavy on concrete, with clean lines and no frills.

It was a symbol of hope in post-war Britain that turned into a symbol of despair.

But by stripping it back to its crumbling concrete shell and redesigning the apartments and the surrounding area, architects Hawkins/Brown and Studio Egret West have made it desirable again.

"When I first saw the building, it was extremely daunting. We had to humanise it," says architect Christophe Egret.

"But the more we came, the more I fell in love with it. The original architects really did a good job and that's what makes it different to other tower blocks. It's the size of the rooms and the light, and the location."

Park Hill past and present, pictures by Richard Hanson, Keith Collie and Daniel Hopkinson

It was the scale that made Park Hill stand apart, as well as an imperative to create a community.

For many who lived there it worked.

There were nurseries, bakeries and "streets in the sky" wide enough for a milk float and the bakery van to make doorstep deliveries. There were pubs that were well used and well loved. The Link, famous for its buffet lunches, attracted wealthy customers. One former resident remembers Rolls Royce cars frequently parked outside.

But for others, crime and neglect saw Park Hill become a no-go area.

The same streets offered quick getaways for petty thieves. Poorly lit walkways made people feel unsafe and the site became dilapidated - graffiti and broken windows blotted the greying landscape.

But its potential was understood. It was described by its former caretaker Grenville Squires as an "elderly lady who just wants to wash her face and put on a new frock".

Urban Splash, which had built a reputation in the 1990s as a trendy property developer in England's northern cities, was the team to do it. The firm took on the building eight years ago, employing the two architectural practices that worked together to transform it.

"This isn't something that would work for every rundown tower block - Park Hill is different," says Egret. "It is the community - the nice shops and nurseries. It was well built, simply built."

danielhopkinson_12154.jpg)

Another strength is its location. Park Hill sits on the outskirts of Sheffield city centre, minutes from the train station and the views stretch across to the Peak District.

It is a sought-after spot that would ordinarily be reserved for expensive glass edifices rather than concrete tower blocks.

But this is a work in progress rather than a finished makeover.

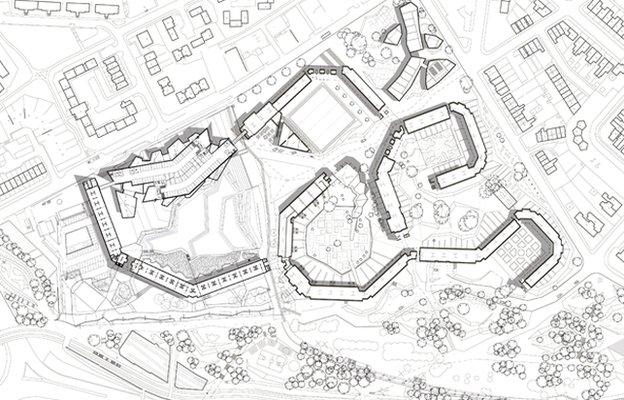

Only one of Park Hill's three huge housing blocks has been redeveloped. The other two, one of which is still partially occupied, await their fate. Egret hopes they will get a similar treatment - possibly with a school and hotel - though the details have not been finalised.

The redeveloped flats are bigger - about a metre has been taken from the external walkways and added in to the homes. Although milk floats may struggle to drive along them now, they still offer a generous amount of space.

Park Hill was stripped back to its concrete structure before being rebuilt

The size of the windows has also been doubled.

Wooden floors have been installed, and work done to improve the entrance, hollowing out a large central cut through the full height of the building in a bid to break up the sense of solidity. New glass lifts are intended to contribute a lightness to balance the concrete.

But as the improvements were made, 750 of the households it was originally built to home were moved out, making way for private owners.

It is a move that has sparked controversy.

Owen Hatherley, author of Militant Modernism, has dubbed it "class cleansing, external", claiming that the starting price of £90,000 a flat may be a bargain for a young professional, but is "inconceivable for the poorly paid and unemployed who used to live there".

A third of the redeveloped Park Hill is now allocated for social housing.

Of the evicted households, 22 have been rehomed within the new development, according to Sheffield City Council. Others have been rehomed around the city.

"The fact is that if councils sell off buildings that aren't working for them, and that they can't afford to maintain, and they reinvest the money in better council housing, then really we should be fine with that," says Kate Faulkner of the Good Homes Commission.

"Furthermore, the common belief now is that mixed use developments are the best way to live - when there is a mixture of social housing, affordable and private owners. It stops ghettoisation."

peterbennett_12185.jpg)

Window size has doubled to maximise views and light

peterbennett_12179.jpg)

But as the social tenants Park Hill was made for are replaced by private owners, has the building failed its original purpose?

"Its failure was not down to the architecture," says Richard Waite, news editor of Architects Journal.

"Sadly many 1960s and 70s buildings have been poorly maintained. But the project shows what, with imagination, can be done with sometimes unloved but generally sound and comparatively roomy post-war blocks. It is an exemplar for many of our cities."

The new apartments - there are 874 of them - now have a concierge and management company. The residents also meet to monitor progress and discuss what needs to be done.

It is hoped the sense of ownership will avoid the pitfalls of the past.

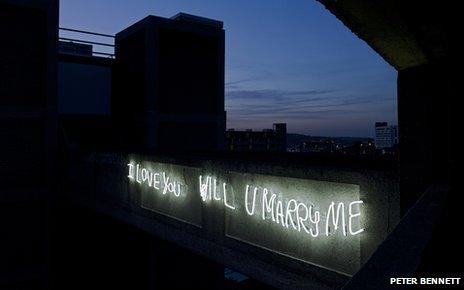

There is also a declaration of love, preserved by the architects and lit in neon for all to now live by. Graffiti scrawled onto one of the bridges says "I love you will U marry me?" Like Park Hill itself, it stood out from the rest as salvageable - a glimmer of hope, improved and preserved.

Evolution of the design

An aerial view of the new Park Hill development, on a hill near Sheffield train station

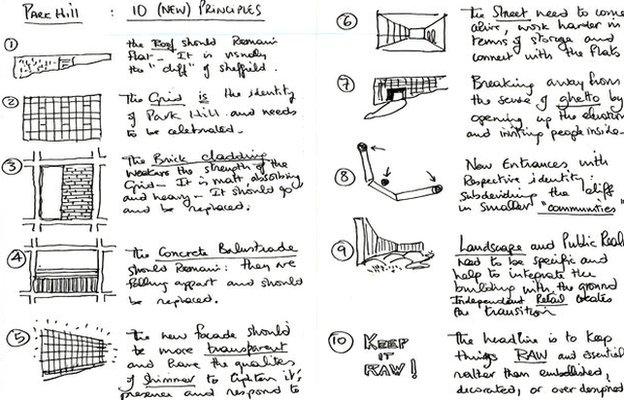

What guided the architects of the Park Hill renovation

The redeveloped flats are bigger, thanks to space taken from the walkways

Video by: John Galliver

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external