Is it right to pay ransoms?

- Published

The killings of US journalists and British aid workers in Syria, and a French hiker in Algeria have highlighted the dilemma for governments over whether to pay ransoms. Should payouts be made to save lives, or do they encourage more kidnappings and fund conflict?

In May 2009, at a makeshift camp deep in the Sahara desert, a group of Islamist militants were preparing to kill a British hostage.

Their prisoner, Edwin Dyer, had been abducted four months earlier with three other European tourists after they left the Festival in the Desert, the annual concert of Tuareg folk music on the Mali-Niger border.

On the morning of his death, Dyer was brought out of his tent and a militant announced that he would be killed.

"Islam tells us to have no connection with the ungodly… Since this is so, the hostage will be executed in the name of God," he declared, according to an account by French journalist Serge Daniel.

A witness said Dyer was "very scared… he surely knew what to expect".

Dyer had been seized with Gabriella Barco Greiner and Werner Greiner from Switzerland, and 76-year-old Marianne Petzold, a retired teacher from Germany. But although they were kidnapped together, their fates were very different.

Petzold remembers how it began - she heard gunshots and saw two pickup trucks approaching their convoy. Tuareg tribesmen got out and shouted at her to get down in French.

"I got out slowly because I didn't want to give in too easily," she says.

She lay down in the sand until the tribesmen ordered her to climb on to a truck littered with bullet shells and Kalashnikovs. As she struggled to obey, one of the men pushed her and she fell and broke her arm.

They drove all day into the desert. Petzold had already lost her glasses and now the hostages were stripped of their jewellery, watches and jackets, and told to put on the blue robes worn by Tuareg tribesmen.

They were soon handed over to a different group. "Now you are prisoners of al-Qaeda," they were told. They had been sold to Islamist militants.

Their new captors knew exactly who each hostage was. "They must have had our passports before we arrived," says Petzold.

The group kept moving and, for a couple of days, stopped at a little valley at the edge of a mountainous plateau. The hostages lay on a blanket in the shade of two trees. There, they met a short, bearded man in his 40s called Abdelhamid Abou Zeid, who was described to them as one of the top commanders of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

Photographs were taken of the prisoners and each hostage was recorded saying: "We ask our government to free us immediately." The kidnappers' translator told Petzold not to worry and that she would soon be released.

Werner Greiner (left) with one of the other hostages

In the days after she was taken, Petzold's family were told by the German authorities that channels of communication had been opened with the kidnappers. They verified Petzold's identity by sending questions about a dog and her family.

What happened after that is unclear. Security experts believe a payment was probably made for Petzold, though German officials have never commented on the case. But after three months in captivity, Marianne Petzold and Gabriella Greiner were released. (Greiner's husband Werner was held for another two months and released in July.) With Petzold in agony from a scorpion sting, the women began a long car ride.

Eventually Petzold saw lights in the far distance. "I then had hope," she recalls. The next thing she remembers is the spectacular sunrise the following morning. They were released the next day.

Marianne Petzold (right) after her release

While there is no proof that Germany paid a ransom, in the case of the Swiss government which acted on behalf of the Greiners, there are official documents referring to the movement of money.

In 2009, the Swiss government denied paying any ransom for the hostages' release. "Swiss officials credited Mali President Amadou Toumani Toure with securing Werner Greiner's release and insisted Switzerland had neither negotiated nor paid a ransom for him," Agence France Presse reported at the time.

But minutes of a special government meeting in Switzerland a few months later show that ministers agreed to make a payment to reimburse the costs of freeing the two Swiss citizens.

A statement from the Swiss parliamentary financial committee, external indicates that "the Federal Finance Delegation had approved funds of three million [Swiss] francs [$3.2m, £1.9m] that the Federal Council had previously requested in connection with the case of Swiss hostages held in Mali".

This is the first and only known official acknowledgement of any government authorising such an action, says Wolfram Lacher, a researcher on northern Africa at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Governments usually hide "behind the secrecy that surrounds the deals", he says.

The ministers also agreed to define the payment as "diplomatic and consular protection", according to the meeting minutes.

Exactly who the money was given to is not clear, but the only condition attached was that a report be produced documenting how it was used and assessing whether anything could have been done to prevent the hostage crisis in the first place.

To this day, that report has been deemed confidential and left sealed.

The leader of AQIM, Abdel Moussab Abdelwadoud

Ransom payments to al-Qaeda and its affiliates are a violation of the United Nations Security Council resolution 1904, external which says states should "freeze without delay the funds and other financial assets or economic resources of these individuals, groups, undertakings and entities." The resolution specifies that this "shall also apply to the payment of ransoms".

And some governments, including the US and UK, adhere rigidly to a no-concession, no-payment policy.

Last month, UK Prime Minister David Cameron underlined this position when speaking about a Briton being held hostage by IS in Syria. "We won't pay ransoms to terrorists who kidnap our citizens," he said. "I know that this is difficult for families when they are the victims of these terrorists - but I'm absolutely convinced from what I've seen that this terrorist organisation, and indeed others around the world, have made tens of millions of dollars from these ransoms - and they spend that money on arming themselves, on kidnapping more people and on plotting terrorist outrages, including in our own country."

The British policy helped determine the fate of Edwin Dyer.

Initially, his kidnappers demanded the UK government pay $10m (£6m) for his release, according to Serge Daniel, who interviewed local tribesmen who were present at negotiations for his book AQIM: The Kidnapping Industry.

Recently released hostages

The release of 63-year-old British teacher David Bolam was announced at the weekend - he had been held by militants in Libya since May. It is thought that money was handed over but it is not clear how much was paid or who paid it. The UK government was not involved in negotiations.

Forty-six Turks and three Iraqis who had been kidnapped in Syria were released in September. At the time Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stressed no ransom had been paid but it was later reported that the hostages were freed by Islamic State (IS) as part of a prisoner swap.

When they said no, AQIM lowered the amount to $6m (£3.6m) but the UK didn't budge.

The group also demanded the release of Abu Qatada, the al-Qaeda-linked radical Muslim cleric who was at the time imprisoned in Britain, saying Dyer would be executed if the demand was not met. Again, the UK refused.

A month after the release of Petzold and Gabriella Greiner, the militants killed their British hostage.

Dyer's hands were tied together. He shouted. Two shots rang out. It's unclear if the shots killed Dyer. Then he was beheaded.

"Edwin didn't deserve to be killed. He was simply the wrong nationality. Had he been German, French, anything else, he would have lived," says his younger brother, Hans Dyer, a 53-year-old British schoolteacher who acted as the Dyer family's representative with hostage negotiators. "And it all came down to money in the end."

Petzold and the Greiners are by no means the only hostages who are thought to have been freed thanks to the payment of a hefty ransom. Since 2003, at least 68 Westerners have been kidnapped in the vast Sahara.

Werner Greiner after his release

More than half of these kidnappings occurred between 2008 and 2012, according to security consultants, foreign governments and human rights groups that monitor attacks on aid workers, tourists and journalists.

The data they have collected suggests ransoms totalling at least $30m (£18.3m) have been paid since 2008 in connection with these kidnappings and that the going rate for a single Western hostage in the region is now about $2m (£1.2m).

Most of these hostages were citizens of countries that are believed to have paid ransoms. Over the past six years, at least a dozen French nationals have been kidnapped in North Africa and the Sahel region, the highest number of any nationality. The majority have been freed, although two were killed, another died in captivity and one is still being held.

In that same period, at least five Spanish, four Italian, two Canadian, two Austrian, two Swiss and two German hostages have been taken. Of this group of 17, one died of natural causes in captivity and the rest were released unharmed. Nearly all of them were aid workers or tourists.

Many European governments say they don't pay ransoms, but they still find a way to make a payment without handing cash directly to kidnappers, says Vicki Huddleston, a former US ambassador to Mali.

"So they paid the money. Then the governments say, 'Well, we didn't pay the money.' So did the family pay the money? Did friends pay the money? Was money taken out of aid accounts in Mali so that Mali could pay the ransom and then be reimbursed?" she asks.

"It's very hidden the way it happened but nobody is released unless the ransom is paid or unless the kidnappers receive some benefit."

In 2003, the German government sent a special envoy from the Foreign Office to work with the Malian government in negotiating the release of hostages, say Huddleston. She never saw money change hands but heard that the people acting as go-betweens were taken care of.

"Let's put it this way… suddenly, it was rumoured that some of the intermediaries had new Land Rovers. The cars would be a payoff," she says.

Killed in Syria

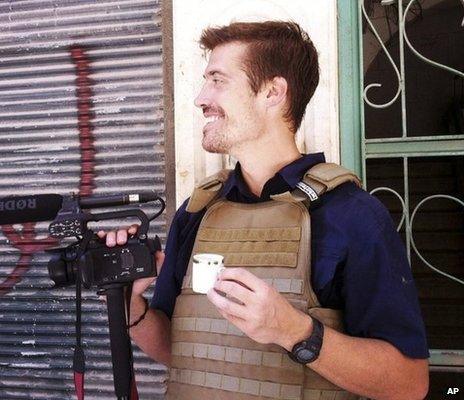

James Foley in Aleppo, Syria, 2012

In the Middle East, ransom rates appear to be higher than in Africa.

Islamic State (IS) militants initially asked for $100m (£61m) for US journalist James Foley. But people close to him believed IS would have accepted far less, possibly even $5m (£3m).

"We didn't believe the $100m demand was the final offer and we didn't think they would harm Jim because of the significant value for him. Sadly, that wasn't the case," says Philip Balboni, chief executive of GlobalPost, the Boston-based news organisation Foley often reported for.

When payouts are made, they undermine other hostage negotiations, says J Peter Pham, the director of the Atlantic Council's Africa Center who advises US, European and African governments.

"It's irresponsible on the parts of these governments. It has clearly created this moral hazard and increased the desirability to terrorists of your own citizens.

A cable from the US embassy in the Malian capital Bamako, released by Wikileaks in 2010, referred to a hostage broker, Abdousalam Ag Assalat. He apparently told the embassy that AQIM had issued a directive in late 2008 in which it offered to pay up to three million Algerian dinars ($36,000, £22,000) per head for Western hostages.

But there was an important detail - according to the cable the directive "specified that the group was not interested in American hostages, presumably because USG [US government] does not make ransom payments."

Hans Dyer has said he agrees with the policy not to pay ransoms, even though he now feels his brother was murdered, then forgotten.

Petzold says it was never confirmed that her kidnappers were paid for her release.

The AQIM commander and leader of the gang who held Petzold and Dyer hostage, Abou Zeid, was killed in Mali in 2013 during fighting with Chadian and French forces

By Derek Kravitz, Colm O'Molloy and Jan Hendrik Hinzel with additional reporting by Lindsey Bever

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.