The gay people pushed to change their gender

- Published

Iran is one of a handful of countries where homosexual acts are punishable by death. Clerics do, however accept the idea that a person may be trapped in a body of the wrong sex. So homosexuals can be pushed into having gender reassignment surgery - and to avoid it many flee the country.

Growing up in Iran, Donya kept her hair shaved or short, and wore caps instead of headscarves. She went to a doctor for help to stop her period.

"I was so young and I didn't really understand myself," she says. "I thought if I could stop getting my periods, I would be more masculine."

If police officers asked for her ID and noticed she was a girl, she says, they would reproach her: "Why are you like this? Go and change your gender."

This became her ambition. "I was under so much pressure that I wanted to change my gender as soon as possible," she says.

For seven years Donya had hormone treatment. Her voice became deeper, and she grew facial hair. But when doctors proposed surgery, she spoke to friends who had been through it and experienced "lots of problems". She began to question whether it was right for her.

"I didn't have easy access to the internet - lots of websites are blocked. I started to research with the help of some friends who were in Sweden and Norway," she says.

"I got to know myself better... I accepted that I was a lesbian and I was happy with that."

But living in Iran as an openly gay man or woman is impossible. Donya, now 33, fled to Turkey with her son from a brief marriage, and then to Canada, where they were granted asylum.

It's not official government policy to force gay men or women to undergo gender reassignment but the pressure can be intense. In the 1980's the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa allowing gender reassignment surgery - apparently after being moved by a meeting with a woman who said she was trapped in a man's body.

Shabnam - not her real name - who is a psychologist at a state-run clinic in Iran says some gay people now end up being pushed towards surgery. Doctors are told to tell gay men and women that they are "sick" and need treatment, she says. They usually refer them to clerics who tell them to strengthen their faith by saying their daily prayers properly.

But medical treatments are also offered. And because the authorities "do not know the difference between identity and sexuality", as Shabnam puts it, doctors tell the patients they need to undergo gender reassignment.

In many countries this procedure involves psychotherapy, hormone treatment and sometimes major life-changing operations - a complex process that takes many years.

That's not always the case in Iran.

"They show how easy it can be," Shabnam says. "They promise to give you legal documents and, even before the surgery, permission to walk in the street wearing whatever you like. They promise to give you a loan to pay for the surgery."

Supporters of the government's policy argue that transgender Iranians are given help to lead fulfilling lives, and have more freedom than in many other countries. But the concern is that gender reassignment surgery is being offered to people who are not transgender, but homosexual, and may lack the information to know the difference.

"I think a human rights violation is taking place," says Shabnam. "What makes me sad is that organisations that are supposed to have a humanitarian and therapeutic purpose can take the side of the government, instead of taking care of people."

Psychologists suggested gender reassignment to Soheil, a gay Iranian 21-year-old.

Then his family put him under immense pressure to go through with it.

"My father came to visit me in Tehran with two relatives," he says. "They'd had a meeting to decide what to do about me... They told me: 'You need to either have your gender changed or we will kill you and will not let you live in this family.'"

His family kept him at home in the port city of Bandar Abbas and watched him. The day before he was due to have the operation, he managed to escape with the help of some friends. They bought him a plane ticket and he flew to Turkey.

"If I'd gone to the police and told them that I was a homosexual, my life would have been in even more danger than it was from my family," he says.

There is no reliable information on the number of gender reassignment operations carried out in Iran.

Khabaronline, a pro-government news agency, reports the numbers rising from 170 in 2006 to 370 in 2010. But one doctor from an Iranian hospital told the BBC that he alone carries out more than 200 such operations every year.

Many, like Donya and Soheil, have fled. Usually they go to Turkey, where Iranians don't need visas. From there they often apply for asylum in a third country in Europe or North America. While they wait - sometimes for years - they may be settled in socially conservative provincial cities, where prejudice and discrimination are commonplace.

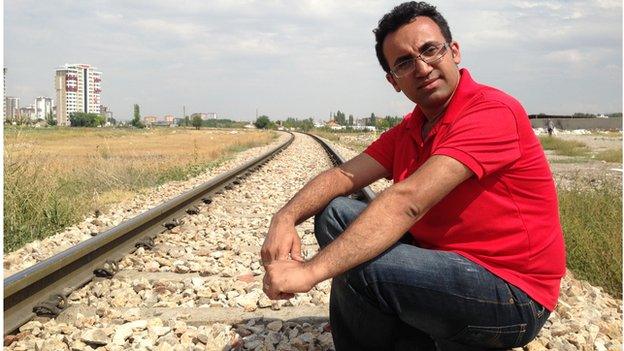

Arsham Parsi, who crossed from Iran to Turkey by train in 2005, says that while living in the city of Kayseri, in central Turkey, he was beaten up, and then refused hospital treatment for a dislocated shoulder, simply because he was gay. After that he didn't leave his house for two months.

Arsham Parsi on the train track that brought him to Turkey

Later he moved to Canada and set up a support group, the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees. He says he receives hundreds of inquiries every week, and has helped nearly 1,000 people leave Iran over the past 10 years.

Some are fleeing to avoid gender reassignment surgery, but others have had treatment and find they still face prejudice. Parsi estimates that 45% of those who have had surgery are not transgender but gay.

"You know when you are 16 and they say you're in the wrong body, and it's very sweet... you think. 'Oh I finally worked out what's wrong with me,'" he says.

When one woman called him from Iran recently with questions about surgery, he asked her if she was transsexual or lesbian. She couldn't immediately answer - because no-one had ever told her what a "lesbian" was.

Marie, aged 37, is now staying in Kayseri after leaving Iran five months ago. She grew up as a boy, Iman, but was confused about her sexuality and was declared by an Iranian doctor to be 98% female.

"The doctor told me that with the surgery he could change the 2% male features in me to female features, but he could not change the 98% female features to be male," she says.

After that, she thought she needed to change her gender.

Hormone therapy seemed to bring positive changes. She grew breasts, and her body hair thinned. "It made me feel good," she says. "I felt beautiful. I felt more attractive to the kinds of partners I used to have."

But then she had the operation - and came away feeling "physically damaged".

She had a brief marriage to a man but it broke down, and any hope she had that life would be better as a woman was short-lived.

"Before the surgery people who saw me would say, 'He's so girly, he's so feminine,'" Marie says.

"After the operation whenever I wanted to feel like a woman, or behave like a woman, everybody would say, 'She looks like a man, she's manly.' It did not help reduce my problems. On the contrary, it increased my problems...

"I think now if I were in a free society, I wonder if I would have been like I am now and if I would have changed my gender," she says. "I am not sure."

Marie starts to cry.

"I am tired," she says. "I am tired of my whole life. Tired of everything."

Watch Ali Hamedani's report on Our World at 16:10 and 22:10 GMT on Saturday 8 November and 22:10 GMT on Sunday 9 November on BBC World News. Assignment is on BBC World Service from Thursday.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.