Would these five changes actually help cyclists?

- Published

Many cyclists believe improving culture among drivers and boosting infrastructure are the only meaningful ways to save lives. But how much effect would some of these smaller changes have?

Issues surrounding cycle safety are often divisive. Here are five of them.

Should helmets be compulsory?

Nothing polarises opinion in the cycle safety debate like the idea of making the wearing of helmets compulsory.

Chris Boardman, ex-pro racer and policy adviser at British Cycling, was heavily criticised this week for deciding not to wear one. "You're as safe riding a bike as you are walking," he says, external. "It's not in the top 10 things you can do to keep safe."

Brain injury charity Headway quickly expressed its "anger and disappointment", pointing out that Boardman himself had written an article in 1998 titled I Was Saved By My Helmet. "It is worrying that a leading figure in the world of cycling should be allowed to put across such a dangerous and irresponsible view," said chief executive Peter McCabe.

In Australia, New Zealand and parts of the US, helmets are compulsory. So far the UK has resisted following suit, although the Highway Code does advise wearing them. And the British Medical Association calls for them to be mandatory. It certainly seems logical to try protecting your head - about three-quarters of cyclist deaths involve head trauma, external.

Even Boardman said "there is absolutely nothing wrong with helmets". The controversy surrounds making them compulsory.

In 2007 Dr Ian Walker, an expert in transport and traffic at the University of Bath, published research that demonstrated how helmets can have a disadvantageous effect on motorist behaviour. He found that drivers would afford cyclists about 8-9cm less space while overtaking if the rider was wearing a helmet.

"The benefits of helmets are hugely exaggerated," says John Franklin, author of Cyclecraft and an expert in cycle safety and accidents. "To put emphasis on them as a major safety aid is considerably overstating the evidence." Helmets are designed for low-speed accidents, primarily without another vehicle present, explains Walker. They're typically only tested up to 14mph, external.

"They shatter if you hit them too hard," adds Roger Geffen, from the CTC cycling charity. "People get very impressed when they see a shattered helmet and think 'My goodness, that could have been my skull' - but what it's showing is that helmets are actually quite flimsy."

The evidence is mixed. The Department for Transport found that, external hospital-based studies tended to show a "significant protective effect" from cycle helmets but wider population studies tended to show "a lower, or no, effect".

But it's easy to argue that some protection is an awful lot better than none. If you fall, anything that can absorb the shock and diminish the impact of a head collision could help.

Others stress looking at the bigger picture, arguing that cycling's health benefits far outweigh its risks. Making helmets compulsory could stop some people riding. "Even in a hypothetical situation where they could save 100% of all head injuries, you'd still end up shortening more lives if [making] people wear them reduced cycle usage by 2-3%," says Geffen.

The debate is far from conclusive. Walker's work did not focus on junctions, where 75% of accidents happen. And most objections are based more on prioritisation and not making them compulsory, rather than saying they have no value.

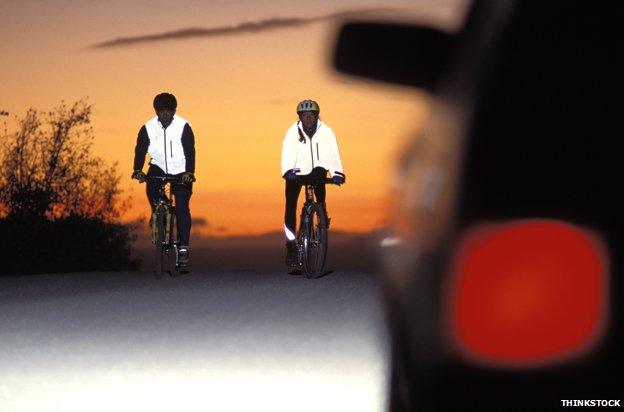

Should high-vis gear be used in daytime?

Some 44% of fatal cycling accidents are caused by drivers failing to look properly, according to independent research firm the Transport Research Laboratory, external.

So it would appear to make sense for cyclists to be as visible as possible. Hordes of lycra-clad cyclists in high-vis colours indicate that many agree.

Reflectors are already a requirement at night, external. And the government's Highway Code advises "light-coloured or fluorescent clothing which helps other road users to see you in daylight and poor light".

But research by Dr Ian Garrard, of Brunel University, casts doubt on assumptions about high-vis. Dressed in various outfits - from casual clothes to professional high-vis gear - Garrard measured how much space 6,000 motorists gave him as they passed his bike.

The different hi-vis outfits worn by Dr Garrard during his research

Clothing made almost no statistically significant difference - 1-2% of drivers always drove dangerously close. Only two outfits altered driver behaviour - one which said "police", and another with "polite". The latter is an intentional imitation popular with cyclists and horse riders, external.

To stand out, what matters most is the contrast with your background, says Geffen. And since your background constantly changes, there's no "best" colour to wear.

But it's important to note that this research was carried out in daytime conditions. Even though 80% of accidents occur in daylight, at night it's a different matter - anything that makes you visible is highly recommended, external.

Reflectors are powerful attention-grabbing mechanisms, says Walker. "We're intrinsically attuned to notice the movement of living things - and pedal reflectors on bikes imitate the up-down motion [of walking]," he adds.

Banning headphones

Headphones dilemma for cyclist

Nearly 90% of people in a BBC poll wanted to ban cyclists from wearing headphones. About one in six cyclists admitted to using them at least occasionally.

"In order to ride safely on the road, you need to be aware all the time of what's happening all around you - not just in front of you," Franklin says.

Listening is an important aid for cyclists, more than other road users, he says. It's important to be able to hear sounds like the change in tone as a driver accelerates. "To be distracted in any way through headphones is a big mistake."

But there's little empirical research. "It's probably so obvious that it's a silly thing to do that no-one will get research funding," suggests Garrard.

Nobody would argue that headphones improve safety. But there are certainly objections to making them illegal for cyclists - at least partly because of what that implies for deaf riders.

The Highway Code for cyclists

The Highway Code gives rules for cycling in England, Scotland and Wales - and includes the following legal requirements:

At night your cycle must have white front and red rear lights lit. It must also be fitted with a red rear reflector.

When using segregated tracks you must keep to the side intended for cyclists as the pedestrian side remains a pavement or footpath.

You must not cycle on a pavement.

You must not carry a passenger unless your cycle has been built or adapted to carry one; hold onto a moving vehicle or trailer; ride in a dangerous, careless or inconsiderate manner; ride when under the influence of drink or drugs, including medicine.

You must obey all traffic signs and traffic light signals.

You must not cross the stop line when the traffic lights are red.

You must ensure your brakes are efficient.

"There's nothing about British roads which says you have to rely on your ears," says Walker. "We have a very formulaic system about who has priority over whom, and that shouldn't actually involve your ears."

Others point to motorists blaring out loud music from car stereos. A study by an Australian magazine, external found that cyclists listening to music could hear more ambient traffic noise than people in cars with the windows up - even with no music at all.

Should cyclists ride in the middle of the lane?

Cycling hazards are not just from moving traffic. Ride too close to the kerb and you risk drains, manhole covers and potentially disastrous doors swinging open from parked cars.

"Positioning is by the far the biggest influence a cyclist can have on his or her own safety," says Franklin. "If I had to teach somebody one thing about cycling it would be that." The optimal position depends on the situation, although never hugging the kerb, he says. The absolute minimum is half a metre, says Franklin.

Geffen suggests a metre from the kerb or line of parked cars is ideal.

But both say that sometimes it's important to move to the middle of the lane, as cyclists are legally allowed to do. "If it's not safe for someone to pass then you take a dominant position to deter them from doing so," Franklin says. "[When] it's safe then you're courteous and allow them to pass."

It's crucial to control when someone can overtake you, says Geffen.

But it's also important how you do so, says Garrard. "Cars to some extent regard overtaking a bicycle as a right. If you look as if you are deliberately blocking them, you can cause more aggression."

And Walker's research discovered that the further one ventures into the middle of the road, the less space will be given to the cyclist by an overtaking vehicle.

So if you come out by 10cm, cars will compensate about 8cm, and increasingly get closer the further out, explains Garrard.

Geffen recommends trying to make eye contact if you take the middle of the lane, so as to humanise the interaction.

Flashing lights or steady lights?

It's illegal to cycle on the road after dark without lights. But only since 2005 has it been legal, external to use only flashing lights. So which are safer?

Much depends on context, says Chris Juden, technical officer at CTC. It's no coincidence that police cars, slow-moving vehicles and ambulances all use flashing lights, he says. They attract the attention of drivers.

In highly urbanised situations with lots of light pollution, flashing lights probably work better than steady ones, Juden says.

"What worries me about night-time visibility is how preposterously brightly-lit cars are becoming," adds Walker. Coupled with other dazzling, distracting city lights, it's harder to see cyclists and pedestrians, he says.

More from the Magazine

But in rural settings a steady lamp at the front might be more useful in illuminating the road ahead, says Juden.

It's a thought echoed by the government's advice for areas without street lighting, external. One problem with flashing lights is that they are harder to track, he says.

"[They] make it very difficult for someone to see precisely where you are," agrees Franklin. Motorists may know you're there but it's harder to judge how far away you are and how fast you're going, he adds.

The wider debate

Many advocates of cycle safety regard all of the above as a distraction from what they say are the main issues - that attitudes among drivers must change and the infrastructure must be improved.

Most personal protective equipment - like helmets or high-vis - places the burden and cost of protection on the rider, they say. There's an ethical incongruence there, Walker says, as riders are effectively paying not to be killed by others.

Most cycling advocates argue instead for deeper structural changes to improve safety - cycle highways or stricter laws.

Boardman and British Cycling's "top 10 things to keep safe, external" features just one reference to personal protective equipment - and that's "removing advice to wear certain clothing when cycling".

Personal protective equipment is the very last step in creating a safe system, says Walker. Take aviation, maritime and rail, he says. "The starting point for every aspect of that system is the driver will make mistakes. It's insane that we utterly ignore human fallibility [for cars and cycling]."

"If we really are serious about trying to make cycling part of our culture, either the cars have to be tamed, or the cyclists have to be segregated," Franklin says.

"A sensible cyclist - and there are some fools out there - has pretty much done all he or she can do for their safety," Garrard adds.

But many motorists - and even generally pro-cycling London Mayor Boris Johnson - claim there are more than just "some" cycling fools. Johnson has even blamed, external risk-taking cyclists for causing many fatalities. It's clearly not just a one-sided issue.

Cycle training courses would be useful for everyone, says Franklin. "They've moved on a long way since children cycling around bollards."

But any changes will be gradual, and until then cyclists still have choices to make on the road. And any influence they have to limit the level of risk might be worth it.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.