The ancient fortress city embracing the modern world

- Published

In recent years Malta has challenged its conservative image legalising divorce and same-sex partnerships. Now the spirit of reform has also breached the imposing walls of the capital, Valletta.

Entering Valletta, the tiny fortified capital of Malta, always gives me a buzz. It's a 16th Century city built in the local honey-coloured limestone, by the Knights of St John.

They had nearly lost this Mediterranean island to the Ottoman Turks in the great siege of 1565 and their new capital was built for impregnability, its awe-inspiring fortifications breached only by a single bridge and City Gate.

As I arrived in Valletta this time, however, the buzz was a little different.

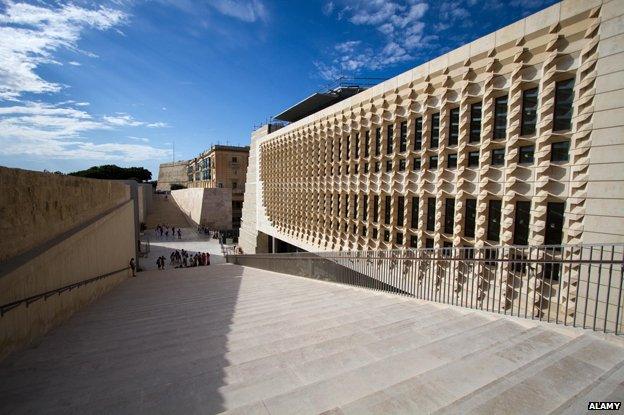

As I crossed the bridge over the deep defensive ditch, the bastion walls on either side glowed with newly-restored freshness. Ahead of me, having emerged from a couple of years of dust and hoardings, stood City Gate - tall, smooth, proud and unquestionably 21st Century.

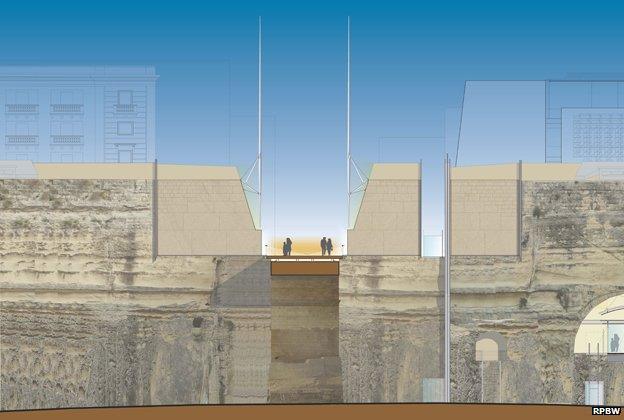

The entrance to Valletta and the square just inside it - degraded by wartime bombing and post-war neglect - have been dramatically redesigned by Renzo Piano, external, the innovative Italian architect of the London Shard. A controversial choice for a Unesco World Heritage City.

When the project was first made public, I have to admit that I thought it would never happen. Malta is - or just possibly was - instinctively conservative.

The Maltese are exceptionally politically engaged, the turnout at general elections here is around 90%, and they love a good argument - this project has provided plenty of material for that - but innovation is another matter.

The Maltese are not generally known for speedy forward motion - except behind the wheel of their beloved cars. I fully expected this audacious project to remain a footnote in Valletta's architectural history.

There is no doubt, however, about what I see before me. The great limestone slabs of Valletta's modern entrance give out on to two broad new monumental stairways leading up to the ancient fortifications.

In the square, a modern open-air theatre sits within the remains of the nation's 19th Century opera house, and, nearing completion, held aloft on stone stilts, stands Malta's first purpose-built parliament.

This is certainly statement architecture - and that is exactly what former prime minister, and driving force behind the project, Lawrence Gonzi intended.

I meet the besuited Gonzi at the legal practice to which he has returned since leaving politics, and we sit in its appropriately modern interior within an historic Valletta townhouse.

Gonzi led Malta into the EU and the euro and tells me he wanted to show that while his country was rooted in its history, it was also, as he puts it "transforming the historical inheritance into a modern outlook in an island ambitious for the future".

Even he, though, has been taken by surprise by how far that change in outlook has already swept.

As a Nationalist - in British terms, conservative - Gonzi never expected to oversee a social revolution.

When a private member's bill pushed him into calling a referendum on the legalisation of divorce, he promised to vote against, fully expecting the Maltese people to do the same.

To his amazement this 98% Catholic country, for centuries held in the tight embrace of the Church of Rome, voted to allow divorce.

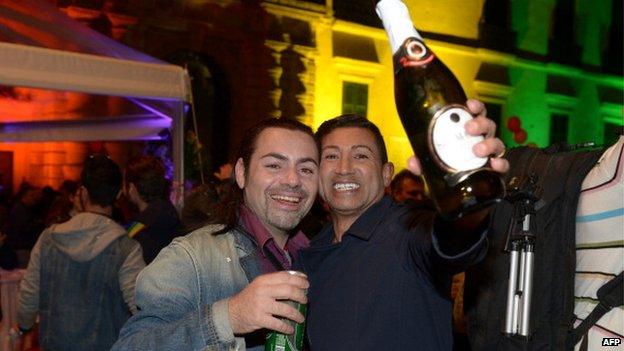

What is more, this year, under Gonzi's Labour Party successor, Joseph Muscat, same-sex civil partnerships have been introduced - something quite unthinkable just a few years ago - and official statistics now show the proportion of Malta's babies born out of wedlock has reached one in four.

There were celebrations when the Maltese parliament approved same-sex civil unions in April 2014

Over coffee with a Maltese friend, I ask what he thinks about this. "Having a child outside marriage is something my parents' generation and even my generation would disapprove of, but once the baby is born, the family always rallies round the mother and child," he says.

"At the end of the day the Maltese are more interested in the fertility goddess than the Virgin Mary," he adds.

EU membership, EU money, increased travel and most of all, internet connectivity are driving a shift towards more liberal values.

What about abortion, I ask Gonzi, could that too be legalised? "No," he says firmly, then pauses, "But then I would have said that about divorce less than five years ago."

So is Malta turning into Sweden or the UK?

"Absolutely not," insists Gonzi, "Malta was a mini-EU even 500 years ago."

"The Knights came from every part of Europe, and were followed by Napoleon and the British. The Maltese took the best of what each had to offer but always remained Maltese and they will now too," he adds.

Knights of St John fighting the invading Turks, 1565

As I walk back to City Gate, the facades to either side of me are both of local limestone. A traditional Valletta palazzo, its characteristic wooden balconies freshly painted, now looks across at the 21st Century geometry of the new parliament.

The modern building's detractors call it "the pigeon roost" or "the cheese grater", but others are impressed by the way that by and large the development manages to be quite different from its historic surroundings and yet respectful of them.

If Malta can follow that as a model for social change it will be doing better than most.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.