The awkward jigsaw of England's boundaries

- Published

- comments

Calls for English devolution raise a thorny but age-old question - how might England be broken up into regions?

Bubbling beneath the surface of England's green and pleasant land is a thick soup of confusion, foaming with indignation and threatening at moments to erupt in volcanic anger. It is a quiet fury born of an ancient conflict between personal identity and public administration.

For those politicians offering to devolve power in England - beware.

My social media accounts have been overflowing with the outrage of Englishmen and women, indignant that I should have even considered options for constitutional reform that are at odds with their particular viewpoint.

For some, the historic counties of England represent the authentic divisions of the land. Others fervently press for the creation of an English parliament for the first time in centuries. There are voices in favour of regions that chime with the ancient Heptarchy, while influential lobbies are pushing the notion of power to cities.

The prime minister's promise of a "new and fair" constitutional settlement has roused profound passions and familiar arguments. A Commons debate on new local government boundaries a couple of years ago revealed something of what is at stake.

"One of the most tragic cases is in the west of my county where a small number of people find themselves, for administrative purposes, in Lancashire," an MP complained. "Can anyone imagine anything worse for a Yorkshireman than being told that he now lives in Lancashire?" Well, no.

"There was local civil disobedience," a man from Bridlington reminded everyone. Members from all over England were stirred from the green benches of the House of Commons to explain how history and geography were being disrespected.

"There is confusion about exactly where Cleethorpes is," one Lincolnshire MP complained. A political opponent sympathised, revealing that some of his constituents "think that they live in Dorset - they do not know that they live in Somerset".

These disputes over lines on maps have been running since the Romans first divided Britain into regions, trying to impose some kind of order on the warring tribes that squabbled over territory. They built walls, laid roads and drew charts in an attempt to contain the locals but it proved a futile exercise.

Roman Britain

Emperor Claudius ordered invasion of Britain in 43 AD

Roman settlers built Hadrian's Wall in 120s and 130s AD - a 73-mile stone wall - from Wallsend to the Solway Firth, to guard the province of Britain from barbarian invaders

Romans remained in occupation for some 350 years

By about 425 AD, after repeated raids by Saxons, Irish and Picts, and the departure of the legions, Britain had arguably ceased to be Roman

When the legions departed, the neatly defined "civitates" quickly frayed as rivalries resurfaced. The arrival of Angles, Saxons and Jutes, formidable warriors from Germany, intensified the struggle and added to the general confusion in much of England.

Public administration is a struggle between the precision of maps and the fuzziness of real life. Historians attempting to make sense of the past prefer to focus on the exactitude of the former rather than the vagueness of the latter, so it is predictable that the 12th Century chronicler Henry of Huntingdon described an Anglo-Saxon England divided neatly into seven kingdoms from 500 to 850 AD. The Heptarchy was made up of Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and Wessex. But his precision glossed over centuries of fierce arguments over boundaries.

In the end, bloody territorial skirmishing between the kingdoms proved an irrelevance in the face of a far greater external threat - the arrival of the Vikings in 793.

Within a decade the Heptarchy was no more. Only the kingdom of Wessex held firm, from where King Alfred began assembling an army. England's destiny was decided in early May 878 upon blood-soaked turf close to a settlement called Ethandun. Alfred was victorious and upon that grim battlefield England was born.

Alfred was responsible for spreading the West Saxon style of administration, dividing areas up into "shires" or shares of land, each shire with a nominated "reeve" responsible for keeping the peace - the title "shire-reeve" becoming shortened over time to sheriff.

It was a shared terror of the Vikings that held the nation together, but a far greater test of Englishness was imminent. Another army of bureaucrats was on its way, an invasion of administrators, clerks, cartographers and planners with designs on the new kingdom. The Normans were coming.

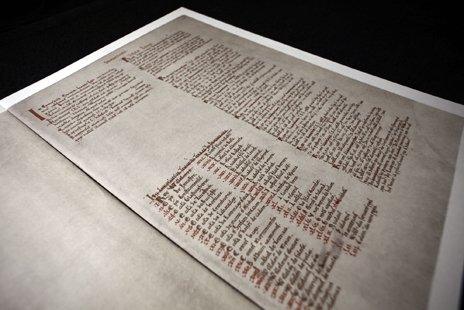

If William the Conqueror had had access to clipboards and those pens you hang round your neck, he would have negotiated a bulk purchase. He sized the place up an then published England's intimate details in the Domesday Book, introducing a bit of Norman styling to the process. The Anglo-Saxon shires were designated counties - the Saxon sheriff often replaced by a Norman count. Both names, however, survived.

Domesday Book

Based on the Domesday survey of 1085-6, which was drawn up on the orders of King William I, it describes the landholdings and resources of late 11th Century England

Book is 913 pages and contains two million Latin words, to describe more than 13,000 places in England and parts of Wales

Named the Domesday Book in reference to the idea of "doomsday", when men face the record from which there is no appeal, external

The County of Gloucestershire, for example, incorporates the Roman name for the main town (Glevum) attached to an ancient British fort (ceaster) then adding the Anglo-Saxon shire (scir) and capping the whole lot with a Norman count (comte). A thousand years of history is scrambled into names that often confound logic and sensible spelling, geographical relics that have come to be regarded as the essence of England.

Industrialisation when it came was no respecter of ancient boundaries, disgorging giant smoking cities that squatted noisily across the countryside without a care for traditional county ways. By the beginning of the 20th Century some influential voices were asking whether the old system really made sense any more.

In 1913, Winston Churchill wondered aloud about the idea of a federal system "in which Scotland, Ireland and Wales, and, if necessary, parts of England, could have separate legislative and parliamentary institutions". He suggested that great business and industrial centres including London, Lancashire, Yorkshire and the Midlands might be allowed "to develop, in their own way, their own life according to their own ideas and needs in the same way as the great and prosperous States of the American Union and the great kingdoms and principalities and States of the German Empire".

But parliament had other matters on its mind, not least increasing Irish agitation for Home Rule, and a world war. A moment when English regionalism might have been seriously considered was lost.

Unlike Scotland, Ireland and Wales, which revelled in their separateness, England's cultural identity was based on the opposite - its importance within the wider United Kingdom and Empire. While the Scots, Irish and Welsh tended to look within their borders to describe themselves, the English looked beyond - identifying themselves, as often as not, as "British" and lamenting the devolution which diminished their sense of imperial centrality.

After World War Two, however, the landscape looked very different. Britain's global influence had declined and many of the industrial regions that had prospered in the 19th Century were struggling in the 20th. In the early 1960s, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan appointed the Conservative leader in the House of Lords, Viscount Hailsham, as his minister for the North East. Donning a cloth cap, the Tory peer hoped an offer of regional regeneration might swing some votes.

It was not enough to save the Conservatives. Labour's Harold Wilson crept over the political finishing line first in the 1964 election and increased his party's majority two years later with promises to help the industrial regions whose voters had handed him the key to Number 10. He was persuaded something needed to be done about England's local government structure, a historic system that appeared increasingly archaic in the white heat of the technological age.

Any answer was going to be controversial, so Wilson did what politicians in Britain traditionally do with a problem too toxic for elected parliamentarians - he set up a Royal Commission headed by a dependable member of the House of Lords.

Lord Redcliff-Maud, a Whitehall mandarin known for his impressive intellect and safe hands, answered the riddle of urban conurbations sitting on a structure designed for rural life by proposing new local councils based on major towns - so-called unitary authorities.

However, members of the Rural District Councils Association (RCDA) were horrified at the idea of being subsumed into modern and soulless metropolitan inventions. They started a national campaign under the slogan "Don't Vote for R.E. Mote" - a play on "remote".

The president of the RCDA, the 5th Earl of Gainsborough and the largest landowner in England's smallest county, Rutland, was dismayed by the prospect of being absorbed into neighbouring Leicestershire. "We are not going to lie down at that," he proclaimed. "People in rural areas do not want decisions made by people 40 or 50 miles away in large towns."

Rutland exemplified the political dilemma - a historical anachronism, famous for the World Nurdling Championships, didn't make sense to the prosaic minds of public administrators, but its very eccentricity played directly to rural England's sense of itself.

Sir Kenneth Ruddle, chairman of Rutland County Council, holds up a poster condemning plans to incorporate Rutland into neighbouring Leicestershire, in 1961

When the Tories returned to power in 1970 they battled to find a compromise. Their Local Government Bill was debated 51 times in four agonising months as MPs argued over boundaries, place-names, geography and history. The result was an act of parliament that, in attempting to satisfy everyone, infuriated millions.

The act created metropolitan counties that trampled all over ancient allegiances. So it was that Greater Manchester included both parts of Lancashire and Yorkshire, while South Yorkshire included parts of Nottinghamshire. Somerset and Gloucestershire became Avon, parts of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire were designated as Humberside, while bits of Cumberland, Westmorland, Lancashire and Yorkshire were cobbled into Cumbria. Bournemouth went to bed in Hampshire and woke up in Dorset. Rutland ceased to exist.

I remember as a cub reporter in the late 70s attending classes on local government administration, a topic so complex and confused that I sensed every twinge of political pain in the reforms. I swotted over single-tier and two-tier authorities, boroughs and districts, Mets and non-Mets, trying to fix in my mind the varied responsibilities and powers of each. Throughout my time in local newspapers and radio, I kept a dog-eared copy of my public administration textbook by my desk in case of emergency.

The social and political turmoil of the 1980s saw the invention of a new and unofficial English boundary - the North-South divide. The Yorkshire Evening Post newspaper is thought to have coined the phrase. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher dismissed it as a myth.

Two things happened - northern England became increasingly resentful at the London-based government, while the Labour opposition became more interested in regional devolution. The party's leader Michael Foot asked an MP with impeccable northern working-class credentials, John Prescott, to produce an "Alternative Regional Strategy", a task he undertook with enthusiasm.

To many UK Tories, this looked like the "slippery slope" to Euro-federalism and a threat to British sovereignty. So the politics of English administration became sharply polarised between the traditionalist instincts of the Conservative Party and the devolutionary demands of the Labour heartlands.

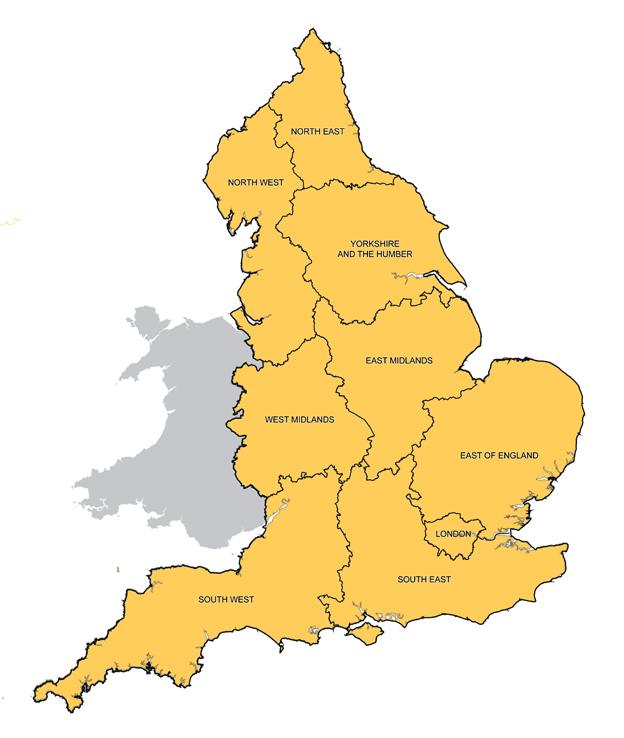

When New Labour came to power in 1997, Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott created the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, which gave him licence to dust off his "Alternative Regional Strategy". With Scotland and Wales granted devolution, the first step in England was the creation of nine Regional Development Agencies (RDAs).

Prescott wanted to go further with elected regional assemblies, but he faced some formidable obstacles. Asked about his ideas for a region in the South West, the deputy prime minister lamented: "It always seemed to me that Cornwall hated Devon, they both hated Bristol and they all hated London".

(It is an attitude I encountered on my recent visit to Newlyn in Cornwall. When I suggested to locals at the Red Lion they might like to be governed by a "city-region" based in Plymouth, mouths fell open in shock.)

Mark Easton travelled to Cornwall to speak to local people about their thoughts on devolution in England.

The deputy PM wanted to press ahead with his devolution plans but, without enthusiastic backing from Tony Blair, he was obliged to test them on the area of England he thought would be most receptive to the idea of regional government - the North East.

Possible devolution boundaries

Regions

Historical counties

Source: Globalization and World Cities Research network

On 4 November 2004, the Great North Vote was held and when the votes were counted, the result was decisive - overwhelming rejection by a ratio of almost 4 to 1. His regional dream was over.

The current government abolished the RDAs and has sought to banish any regionalist ideas in England to the extent that civil servants resorted to the use of an acronym when discussing the issue: TAFKAR - the areas formerly known as regions.

What is revealed in all of this is an important facet of the English personality. After 2,000 years of administrators trying to bully the population into neatly defined blocks, England has developed a natural distrust of straight lines on a map. They prefer the quirkiness of a complicated back-story, they like things to be irregular and idiosyncratic, revel in the fact that Americans cannot pronounce, never mind spell, Worcestershire.

Devolution to England is firmly back on the political agenda, but as the politicians toy with ideas of city-regions, regional assemblies and an English parliament, they should prepare themselves for seriously impassioned reaction to whatever they propose.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.