The time when spy agencies officially didn't exist

- Published

This week the new heads of intelligence agencies MI6 and GCHQ took up their posts. Once shrouded in mystery, the spy chiefs are now public figures.

The appointments of Alex Younger and Robert Hannigan were announced with brief biographies and photographs, yet it was not that long ago that the public knew nothing of their roles or the organisations they led. As chief of MI6, Younger is known as "C", the codename of the first chief Sir Mansfield Cummings.

This is now common knowledge. But in 1923 the novelist Compton Mackenzie was prosecuted, among other things, for revealing the letter and to whom it referred. Such was the secrecy that when the judge asked when Cummings had died, the prosecution barrister, the attorney general and "K", the then-head of MI5 did not know. The only person in the room who did know was Mackenzie.

It shows how secretive the service was in its early days, that simply mentioning the name of a dead chief led to a court case, says Christopher Andrews, the writer of MI5's official history.

Alex Younger (l) and Robert Hannigan, new heads of MI6 and GCHQ

Cummings was the first chief of what was then the Secret Service Bureau in 1909. As far as the public was concerned it did not exist, the writer of MI6's official history Prof Keith Jeffery says. It was a time many people working in intelligence "look back to fondly". The eccentric chief would wear disguises to see if colleagues would recognise him, kept photographs of those which had worked well, used sword sticks and invisible ink. "He loved and was very engaged with the technology of it all," Jeffery says. Rumours circulated that he would stab his wooden leg with a letter opener in interviews to see if potential employees flinched.

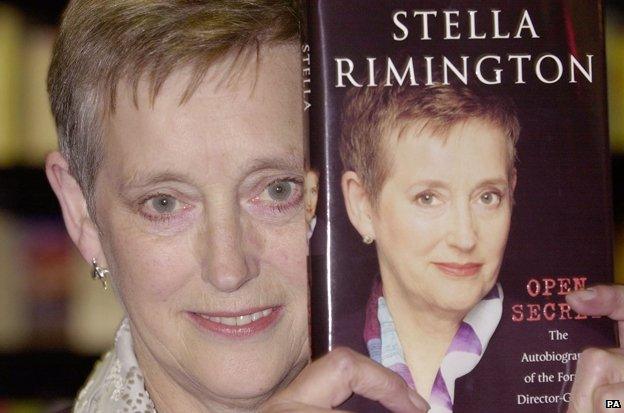

In 1992 Dame Stella Rimington was the first chief of MI5 to be officially named. "Her neighbours discovered what she did and her children found out for the first time," Andrews says. But MI5 only released her name. Official pictures of her were only released after a paparazzo got a "very blurry picture of her out shopping", Andrews says.

But even if the heads of the intelligence services have been revealed, Ben Macintyre, the historian and author of A Spy Among Friends, says the "humble worker bees" and their work have not. If anything, it is more secretive. "Up until recently even reporting the colour of the carpet in MI6 was a breach of the Official Secrets Act."

007 would have been an officer, not an agent. Officers are employees, whereas an agent is a secret source used to gather information. "There is not a single case of SIS ever disclosing the identity of agents even after something like 100 years," says the intelligence historian Nigel West. Keith Jeffery, when researching his history of MI6, spoke to active officers about whether they would be happy for their identity to be revealed 60 years or so down the line. "Some were happy to be part of the history of it," he says. "But because it is technically living a lie, some really did not want their families to find out."

Dame Stella Rimington promotes her autobiography

MI5 was recognised in law in 1989. "There shall continue to be a Secret Intelligence Service," were the words that officially confirmed that MI6 and GCHQ existed, in the 1994 Intelligence Services Act. The government was more relaxed about MI5, says Christopher Andrews. But MI6 was a more difficult proposition. It is "un-embarrassing to admit to an organisation which caught spies. But it was embarrassing to admit that you had spies of your own".

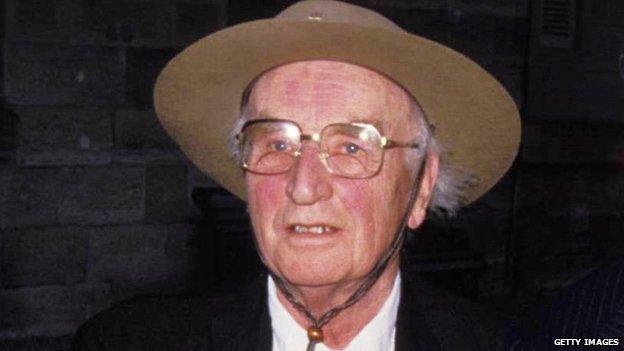

It was an open secret that all three of the intelligence agencies existed - MI5 had been mentioned in parliament in 1952 - but the government reluctantly first acknowledged MI6 in 1986. Peter Wright, a former senior member of MI5, published a memoir, Spycatcher, in Australia and the British government tried to bring an injunction against him for breaching the Official Secrets Act.

The Spycatcher affair

Peter Wright, author of Spycatcher

Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer was a bestselling 1987 book co-written by former MI5 officer Peter Wright, and journalist Paul Greengrass (later a successful film director)

Wright claimed he had been assigned to unmask a Soviet spy in MI5, whom he claimed was a former director general, Roger Hollis; the book also describes British intelligence operations, such as a plot against a former prime minister, Harold Wilson

Published first in Australia, it gained notoriety due to a long and unsuccessful attempt by the British government to ban it; the attendant publicity helped Spycatcher become an international bestseller

The Cabinet Secretary Sir Robert Armstrong flew out to appear as a witness. Although upon landing he was so "riled" by the press attention that he "lashed out with his briefcase at photographers and pushed one of them against a wall", the Times reported.

In the dock he was asked the awkward question: "Does MI6, Britain's secret intelligence service, exist?" He declined to comment. The Times reported that "MI6 is the one area of intelligence work which still requires, in government eyes, the glazed-look approach". Although he refused to acknowledge MI6 then, the government was eventually forced to release a summary of memos between sections of MI6. This confirmed the service's existence.

The GCHQ building in Cheltenham is a recognisable landmark

But as well as knowing they exist and who runs them, we now know the headquarters of the agencies. All three of the services are based in recognisable headquarters - the MI6 building has featured in Bond films since Goldeneye in 1995, the GCHQ "doughnut" is regularly seen on news bulletins, and MI5's Thames House, like MI6, is a stop on a James Bond boat trip for tourists.

"If you're going to get a taxi to Albert Embankment they think you are a spy," Jeffery says. But West says these public locations are not part of them wanting to have more of a public face. "If they could find a big enough anonymous building in London they would move tomorrow." MI6's old headquarters, an unmarked concrete tower called Century House, "started making people ill and the only building being built at that time which could house them was the Lego-looking building on Vauxhall". They were forced into view, he says.

MI6's headquarters: a "Lego-looking building in Vauxhall"

In the past they were a little more proactive at hiding their location - 54 Broadway, which MI6 occupied from 1926 to 1964, was marked with a brass plaque describing it as the "Minimax Fire Extinguisher Company". But this disguise did not work for long. In his book on British spying, Michael Smith recounts how after it became known MI6 was looking to move building, the landlord started doing viewings. Unfortunately one was a Russian trade delegation and staff were forced to rush around ripping maps off the walls.

"They know they have to have a public face now. These are huge government organs and we want to know who is running them," MacIntyre says.

More from the Magazine

But Harry Ferguson, a former MI6 officer and now author, says it has "actually gone backwards" in terms of openness. Plans for a press office were scrapped and a BBC series which MI6 collaborated on was greatly cut down after the "dodgy Iraq dossier scandal" in 2003. "All of a sudden it was a case of batten down the hatches. All in a couple of days."

There are also strict controls on former officers. Ferguson says he and a few others can speak about their time with the service because of "special circumstances". But many others are annoyed that they can say nothing, while their CIA counterparts publish memoirs.

"There has always been a certain amount of openness. But even the doodle pads by the phones are stamped with 'top secret' still."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.