Seasonal Affective Disorder and the difference from winter blues

- Published

It's 30 years since the term seasonal affective disorder (SAD) was first used to describe winter depression. Is it overused today?

In 1984 psychiatrist Norman Rosenthal first used a term that changed the way people thought about winter.

Seasonal affective disorder describes a type of depression with a seasonal pattern, usually occurring during winter. A lack of light is thought to affect the part of the brain that rules sleep, appetite, sex drive, mood and activity levels, external. Patients experience lethargy and a craving for sugary snacks.

Rosenthal included the term in a paper he co-wrote following a move from the warm climate of Johannesburg in South Africa to the north-eastern US, with its more severe winters.

"It took about three years of seeing the winters alternating with the summers," Rosenthal, who lectures at Georgetown University in Washington, says. "It was a sort of given that people were grouchy in the winter, not so happy."

But the work of Rosenthal and others established that there was more to it than that for some people. The cultural idea of many people being less happy in winter was not to obscure the fact that for a smaller group of people something more serious was happening. "It becomes a medical thing when it has consequences in people's lives, like not being able to get to work or their quality of life going down the drain," says Rosenthal.

The Norwegian town of Rjukan has erected giant mirrors to reflect the sunlight

SAD has been accepted as a condition by many. The NHS offers advice, external, And it has also gained significant currency in popular culture - with the term being widely used by laymen.

In the UK the term was first used by the Times in 1988, in a piece highlighting a link between afternoon shift workers and a lack of daylight. Since then it has gradually filtered into common parlance. According to Google Trends the term is still much more commonly searched for in Canada and the US, with the UK third.

Rosenthal admits the acronym, which suggests the kind of feeling sufferers get, was chosen to make a maximum impact on the media. It seemed to work.

Sarah Jarvis, the Jeremy Vine Show doctor, noticed an increase in people coming in to her surgery citing SAD about a decade ago. Many turned out to have "winter blues", she says. "It's very difficult because the winter blues are really common. Most of us find our mood is affected."

It's similar to the way people mislabel other conditions, taking a term they have heard, says Jarvis. "Most people don't get headaches; they 'get migraines'." To have genuine SAD a patient must have suffered depression two years running, she explains.

Winter blues often involves a lack of sleep while SAD means people are permanently tired and spend longer in bed, she says. Jarvis estimates between 3% and 5% of the UK population might have SAD, with one in eight (12.5%) having the more mundane "winter blues" - a much less well-defined change in mood.

Rjukan is surrounded by mountains but sunlight is directed downwards by giant mirrors

Rosenthal suggests that 6% of people in the US suffer, external from the most acute form of SAD and that another 14% get winter blues. A study found the severest form affected just 1.5% in the southern state of Florida, which averages seven hours of sunshine a day even in winter, external, rising to almost 10% in the northern state of New Hampshire, which gets just four hours daily in November and Decembe, externalr.

Jenny Scott-Thompson has been diagnosed with SAD. Every year between September and April she would feel suicidal. After getting through a maths degree at Cambridge University and a job in the City of London, the suffering of winter got too much.

"I struggled with periods of exhaustion and misery that seemed out of proportion to what was going on in my life," she says. Scott-Thompson sought help and was diagnosed with SAD.

The doctor recommended spending time next to a light box and going away for winter sun. Suddenly her life took on a different complexion, she says. "It was incredibly effective. That year (2009-10) was the first time in six years that I got all the way from September to April without feeling suicidal at all. I realised that not everyone is used to spending half the year hating yourself and wanting to die."

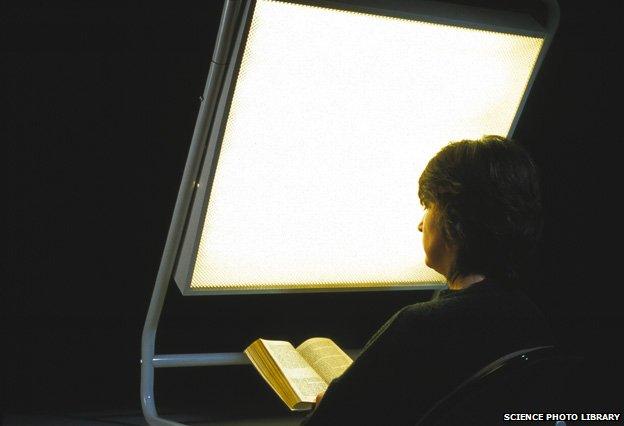

Rosenthal advocates the use of electric lights, among other methods, to offset the effects of SAD, including in the UK, whose population spends a "long time in gloom" in winter, as much because of large amounts of cloud as the shortness of the days.

Light therapy is long established, the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates advocating healing properties in exposure to the sun. From the late 1800s heliotherapy, or phototherapy, became popular. Some tuberculosis-infected children from slums, where little sunlight was available, were taken to retreats where they could spend as much time outdoors as possible.

Light treatment is used for a number of ailments

Light treatment has been used for other ailments. In 1903 Faroe Islands physician Niels Ryberg Finsen was awarded the Nobel Prize for inventing an ultraviolet lamp for tuberculosis of the skin.

But in 2009 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ruled there wasn't enough evidence, external to justify the NHS in England spending money on this type of treatment for depression. The guideline is currently under review.

Rosenthal says a lack of direction from above means doctors are not asking patients the right questions, such as whether the symptoms they describe are seasonal or year-round. "I've just come to terms with the limits of my ability [to persuade people about SAD]," he says. "People have to find out about it to some extent on their own."

But not all scientists believe SAD is a distinct condition. In 2008 the Norwegian psychiatrist Vidje Hansen, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Tromso cast doubts.

"If you were going to find SAD anywhere, it would be here in Norway, where we have no sun for two months of the year," he said. Instead there was no correlation between depression and the amount of light after an analysis of 8,000 people in Tromso, external, he wrote.

Hansen's view is apparently not shared across Scandinavia, large parts of which get hardly any sunlight in midwinter, external. In the northern Swedish city of Umea, an energy company installed phototherapy lights in bus shelters, external to help residents cope with the darkness of winter. The Norwegian town of Rjukan, surrounded by mountains, erected giant mirrors, external to redirect sunlight on to the main square.

The Seasonal Affective Disorder Association campaigns for more understanding. One of its members, Helen, suffered depression when she moved from a light modern flat into a dark Edwardian terrace.

"I knew that I hated darkness and dull weather but didn't make the connection because I didn't know there was one," she says. "The world is now awake and artificially lit 24/7 and we have lost our connections with seasonality and the real rhythm of the days. For some of us, this is bad news."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.