Do British towns look too similar?

- Published

Six decades ago a critic launched a withering attack on the tendency toward a bland "subtopia" in British towns.

April 1955 witnessed a changing of the guard. That month Anthony Eden replaced the 80-year-old Sir Winston Churchill as prime minister.

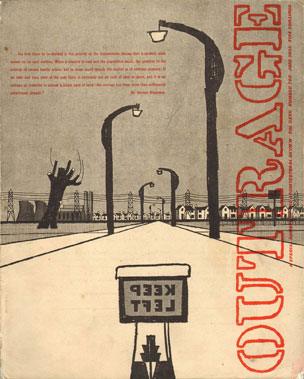

Two months later, the Architectural Review magazine printed Outrage, an essay by critic Ian Nairn. It sparked a debate over architecture, conservation and planning which still resonates today.

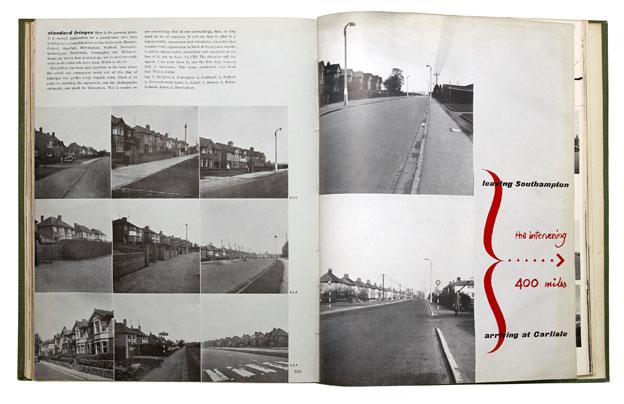

In Outrage, the singular and passionate Nairn recounted a journey he had made in a Morris Minor from Southampton to Carlisle.

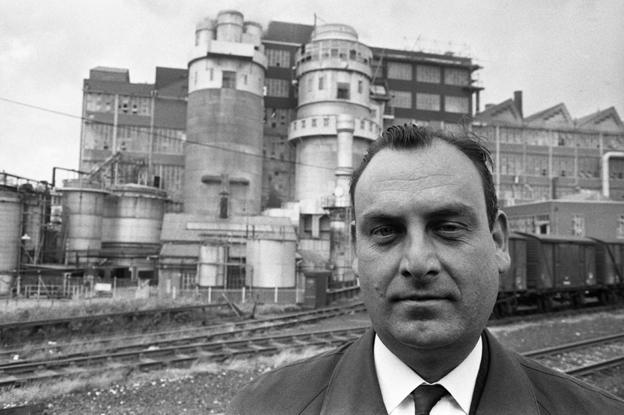

Nairn in Manchester

He summed up what he saw in one word - "subtopia". "Its symptom," Nairn contended, with photographs to prove his point, "will be that the end of Southampton will look like the beginning of Carlisle; the parts in between will look like the end of Carlisle or the beginning of Southampton."

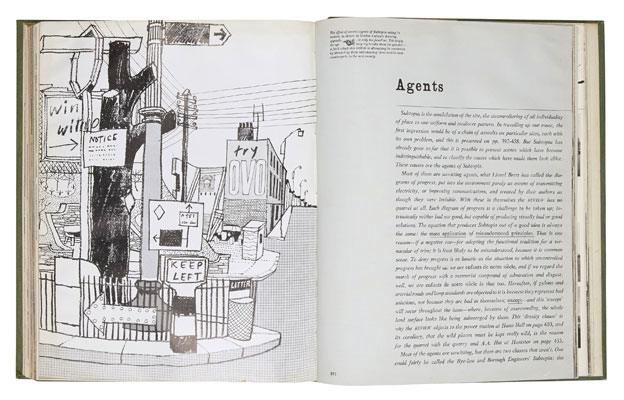

In doom-laden tones he explained: "The Outrage is that the whole land surface is becoming covered by the creeping mildew that already circumscribes all of our towns. Subtopia is the annihilation of the site, the steamrollering of all individuality of place to one uniform and mediocre pattern."

He dubbed his essay "a prophecy of doom" and it also aimed to be a rallying cry, calling for the protection of "characteristic places" which aided the survival of a "characteristic English consciousness".

The piece did go on to provide a philosophical boost for architectural conservation, but six decades later has Nairn's prophecy come to pass?

Ian Nairn's Outrage

Subtopia was coined by Nairn to "describe the annihilation of the site, the steamrollering of all individuality of place to one uniform and mediocre pattern"

His targets were concrete lamp standards, 'Keep Left' signs, municipal rockeries, chain link fencing, poles and other elements that he thought destroyed the visual quality of a place

The Daily Mirror described Outrage as a "devastating and appalling photographic indictment of the industrial disease that is ravaging the once lovely face of England"

Architecture critic Jonathan Glancey believes it has. Subtopia, which he terms "nowhere sprawl", has been "an accelerating process'" since Nairn wrote his piece.

"We built incredible junk estates. He identified the problem and it just wasn't going to go away."

During the post-war years, Glancey explains, buildings were thrown up "too fast, too cheap, too shabbily".

Nairn was writing at a time of extremely rapid building. A 1951 government report estimated that 450,000 houses had been destroyed or severely damaged by enemy action during the war.

In addition, the conflict had led to the deterioration of existing housing stock, as it had prevented maintenance and virtually stopped the building of new properties.

There was little consensus among experts but one estimate indicated that 1.5 million new houses would need to be built, to provide each family with a home and eliminate overcrowding.

High rates of marriage and birth rates just added to this figure.

And, though house building saw a rapid rise in the post war years - from 55,400 a year in 1946 to 227,616 in 1948 - post-war planners had, by definition, to build fast and build cheap.

City centres throughout Britain were transformed, slums were cleared and, conservationists argued, many historic buildings and townscapes were destroyed as well.

Critics say that subtopia today manifests itself in a number of ways. Two of these, the blander housing estates and so-called "clone" High Streets, are regularly in the news, external.

The same coffee shops and card shops, the same pharmacies and pizzerias, can be seen on High Streets hundreds of miles apart.

But, although the image of the "clone" High Street may have held sway for many years, the picture has changed slightly in recent years. The betting shops, coffee shops, financial institutions, discount stores, charity shops and convenience stores are thriving but empty retail outlets are becoming a more common sight.

Nairn was worried that Southampton...

... would soon look like Carlisle...

Recent figures from the Local Data Company (LDC) which monitors more than 500,000 retail and leisure premises in the UK, show that, on average, about 9,000 retail and leisure units - the equivalent of five Manchesters - have been empty for more than three years.

"Retailers like M&S and Next have moved out of the High Street into shopping centres and retail parks," explains the LDC's director, Matthew Hopkinson.

The image of a chain shop-dominated UK, which would prove Nairn's thesis right, doesn't completely bear out. Independent shops still account for 66% of retail units, although the figures across the country vary significantly.

Almost 90% of retail units on London's Caledonian Road are run by independent traders, while in Salford, Greater Manchester, this figure is only 24.4%.

According to the LDC, other towns with a dearth of independent shops include Bracknell, Milton Keynes, Solihull and Cwmbran.

The architectural writer and broadcaster, Gillian Darley, who is also Nairn's biographer, believes that "the out-of-town shopping centre draws life out of the towns". But she adds: "Each of these waves of awfulness correct themselves because we have to keep tidying things up and pushing things around. Then it crops up somewhere else."

Some of new housing of today would also have appalled Nairn, reminding him of the ribbon developments built along main roads that he criticised, suggests Darley, "except they would be cul-de-sacs, the houses would be detached but you could only put a bit of paper between them and that's it, that awful debasement of standards".

Closed-down shop in Burslem

The same pressures apply in the UK in 2015 as 1955 - the country needs more houses, and many High Streets need overhauling.

But in the recent past, Glancey argues, "there were modern developments but with a bigger spirit".

"The Barbican is terrific. It's been through every possible criticism for being Brutalist and ugly. It's pretty magnificent. It's more baroque than brutal."

To Darley, "subtopia's current message is 'no space, absolutely squeeze it to the ultimate and price it to the top'."

And Glancey has his own, Nairn-like, warning.

"Towns and cities have a purpose. They have jobs, they have roads, they have schools.

"All this new stuff... has no centre, no heart, no reason to exist other than to supply housing for people."

More from the Magazine: Radical concrete

Thamesmead, built during the 1960s, was designed as a futuristic city

JR James helped launch the new towns of Newton Aycliffe and Peterlee in the late 1940s, becoming chief planner at the Ministry of Housing and Local Government from 1961-1967

He left a collection of nearly 4,000 slides amassed over several decades of interest in the work of planners around the UK

The slides record some of the most radical buildings in the UK: Brutalist high-rise Thamesmead flats, The Brunswick Centre in London, Trinity Square in Gateshead (also known as the Get Carter Car Park), and many others

Watch Ian Nairn's 1972 series Nairn Across Britain on BBC iPlayer