A Point of View: Why do some people dislike hearing foreign languages in the street?

- Published

Unfamiliar words can make people feel uneasy, but embracing new languages is good for us, writes AL Kennedy.

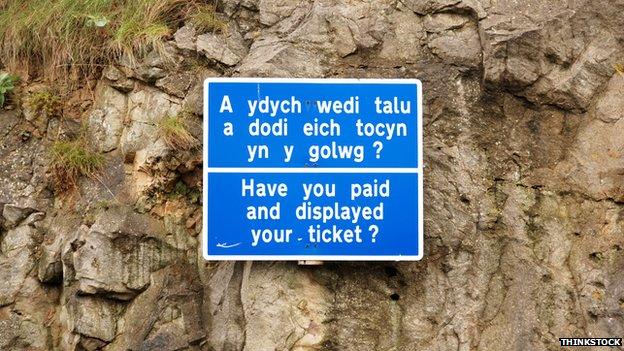

My grandmother was wonderful but unusual. She had preferences. She hated countryside - she'd rather sit at a rural bus stop in hopes of a passing crowd than look at a mountain. She could take offence in an instant, but like many delicate people, could be just plain rude without noticing. One of her peculiarities only emerged when we were holidaying in Wales - sadly, in an area short on people but heaving with mountains. We were staying in a village where many of the residents spoke Welsh and I was a kid enjoying wishing people "bore da" (good morning) and saying "diolch" (thank you) a lot. But my grandmother reacted with a paranoia remarkable, even for her, whenever she heard Welsh. No matter the circumstances, she was absolutely sure that if someone wasn't speaking English, they were speaking about her - and weren't being nice. The holiday got tricky.

I learned later Gran's parents were Welsh-speaking, but hadn't passed on the skill, and if they were talking in Welsh around rumbustious young Milly she could be fairly sure she was in trouble - again. She translated this early experience into an assumption that an entire nation would harbour one of Europe's oldest living languages solely to plot against her. Even the road signs made her twitchy.

Wales - "heaving with mountains"

I'd forgotten this until lately when I've heard repeated variations on the theme of: "When you get on the bus, walk down the street - you don't hear any English being spoken." On the one hand it is quite a bland statement and on the other, it has a lot of my grandmother about its wider meanings - this worried distrust of hearing people and being unable to understand them.

I can appreciate that when I hear people speak in unknown tongues, I might become anxious because the unknown can seem fearful. But beyond emergencies when I might not understand instructions, does this fear make sense? I mean, I do enjoy eavesdropping, but I've never overheard a stranger even mention me in passing. And I have been clearly a British person in France and Germany, while having a modest grip of French and German and I have to say, I just didn't come up as a topic of conversation even when those around me were within what they might have considered the privacy of their own languages. Maybe I'm boring. Actually, I tell a lie - I did once walk through a train from Berlin wearing a fur hat and someone remarked that I must be East German… Maybe I'm really boring.

And maybe the fear of unknown languages is an inevitable problem in Britain. While around three quarters of Brits apparently think all Europeans should have one other language, we may also be hoping that everyone else's will be English - fortunately, it often is. In 2013's European Survey on Language Competences the UK didn't excel. Statistics for the whole UK and all schools aren't available but only 10% of surveyed 14 and 15-year-olds achieved fluency in another language. The European average is around 40% and can be much higher. More funding is being released for modern language teaching by Westminster and the Scottish Executive, but teachers and businesses have been bemoaning the situation for decades. How do you learn from or do business with someone you don't understand? And yet long-term investment in understanding foreigners doesn't always play well - even if it pays generous dividends.

Research from York University in Canada and Edinburgh University, among others, suggests having a second language slows brain ageing. Learning one other language can make it easier to acquire more, but can also improve your maths. If you want to increase your average salary - learn another language. And if you want to improve your ability to hear… well, there's evidence to suggest an additional language doesn't only improve cognitive function, it can enhance our auditory neurology and as a result we can remember more and are better at paying attention. Being better able to speak, helps us listen.

But listening isn't just about words spoken. Many human interactions aren't about words at all and, even when we do speak, non-verbal communication plays a huge part in how we understand each other. Blake Eastman of New York's City University sets the non-verbal component in interactions at between 60% and 90%. So, when we feel strange words are overwhelming us, is it less about vocabulary and more about the perceived strangeness of the people speaking? When we say, "I don't understand them," do we mean exactly that?

As a woman performing comedy, as a woman trying to get my car repaired, I've known what it's like to be somehow inaudible. Many of us have much less trivial experiences of being unheard in ways that have nothing to with what we're saying and everything to do with who we are - and that can shatter lives. There are times when our public discourse seems to have become one of hypersensitivity and discourtesy, ham-fistedly combined, of reaction, stridency and paranoia - a kind of expression of poor listening.

And in our racing, sound-bitten, gotta-have-a-picture-with-that-story age, listening can seem to be a dying art. Listening research really took off when the wireless stopped being king and listening started to be a fading art - with predictable effects on learning and all kinds of relationships. Hence all the online surveys and courses available in active listening which remind us to nod and look at the person speaking and respond supportively. This can produce freakish behaviour with people nodding like desk toys and staring, while they parrot: "I'm listening." But it can strengthen the skills we use naturally when we pay close attention, perhaps to those we love, perhaps to those we'd forgotten we love, or simply to those who deserve our courtesy - when we choose to share their pace, speak with them, breathe with them.

It is difficult to communicate - there are so many languages and accents and cultures and individuals with quirks and we can't know about them all. And women are said to be more likely to enjoy discussing problems, while men are more likely to skip the bonding and suggest fixes - so "mansplaining" and frustrations can abound. And time is short and you have to hit the bullet points, say it all in 140 characters or less. And our public perception is often of an unheard electorate and an inattentive parliament - a Westminster full of catcalls, interruptions, deflections, computer-gaming distractions (all contra-indicated by advocates of effective listening). This infuriates both MPs who are trying to be responsive and those who appear in public staring, nodding and telling us they're listening. And we all get tired and bewildered and the world can become strange for many reasons in ways that may mean strangers and strange words leave us feeling lonely, helpless.

Welsh words

Good morning - Bore da

Goodbye - Hwyl fawr

Thank you (very much) - Diolch (yn fawr iawn)

Please - Os gwelwch yn dda (formal) / Os gweli di'n dda (informal)

Cheers! (Good health) - Iechyd da!

Happy Birthday - Penblwydd Hapus

Which is why Granny did me a favour in Wales. That trip made me want to learn languages, enjoy strangeness, and so I have. I travel a lot and with even just yes and no, please, thank you, excuse me and a few versions of hello, life can be pleasant in any language and the strange can stop being strange. Start being simply more and the world swings open. And I don't listen well - I'm a person who prefers mountains to people and who monologues at you on the radio - I'm not listening to you, am I? When I get home from travelling I often drop please, thank you, excuse me, which means I am rude without noticing. And because I don't absolutely have to, I can stop giving close attention to others in ways that help me understand them, so we could be of use to each other, or just smile, or simply go on our ways contentedly. Which isn't about vocabulary, it's about remembering everyone deserves my courtesy until they prove otherwise. More words give me more paths to and from the hearts of others, more points of view - I don't think that's a bad thing. Particularly now I know I missed too much of my grandmother - my wonderful, unusual, hard-to-translate grandmother - because I didn't give her enough attention, didn't listen, and then she was gone.

More from the Magazine

A Point of View is usually broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 GMT and repeated Sundays 08:50 GMT

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.