Would it be realistic to renationalise the railways?

- Published

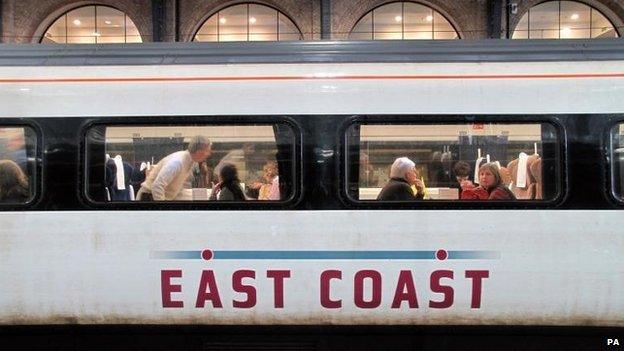

East Coast main line train services have passed from public to private hands. But is it realistic to talk about the rail network ever being renationalised?

A rare experiment in public ownership has come to an end.

Supporters say that Directly Operated Railways, a state-run body, rescued the East Coast main line after the collapse in 2009 of National Express's franchise. The firm had been unable to deliver promised revenues to the government.

Directly Operated Railways handed a billion pounds in premiums to the Treasury during its period in charge.

But after the government decided to return the franchise to private hands a bidding process in November, external gave it to a consortium of Virgin and Stagecoach - called Intercity Railways.

The unions and Labour have argued the line - which runs between London and Edinburgh - should have been kept in public hands.

Labour has suggested that it will review the franchising system and allow the public sector to bid to operate rail lines. The Conservatives say that would be unworkable.

A British Rail poster from 1978

John Major's Conservative government split up British Rail into a series of franchises 20 years ago.

Since then the number of passengers travelling on the railways has doubled. But the public subsidy has risen.

A YouGov survey, external in May 2014 suggested that the public supported renationalisation by a margin of 60% - 20%.

But how easy would it be to renationalise the railways?

Not difficult at all, says James Abbott, editor of Modern Railways. Network Rail, which manages the track, is already in public hands. The train companies have time-limited franchises. Once these have expired the government could get them back at no cost to the taxpayer.

Most of the franchises expire during the next parliament, which runs until May 2020. The exceptions are East Coast (2023), Thameslink, Southern, Great Northern, Chiltern (2021), and Essex Thameside - branded C2C - (2029).

If a government wanted the process to be quicker - or to avoid a mixed system - it's hard to say how much buying out the private sector would cost.

Mark Smith, who used to set fares at the Department of Transport and now runs the website The Man in Seat 61, says you could estimate what payouts would be needed by looking at each franchise's annual profits and then multiplying by how many years are left on it.

The rail industry says about £250m is made in profits by the franchisees each year, about 3% of turnover.

The British Rail Class 47 locomotive 2

There's also the question of UK and European Union legislation.

The Railways Act 1993 states that the public sector cannot bid for franchises. Either a totally new act would be needed to oversee nationalisation or there would need to be significant amendments to the existing act.

The EU says it wants to open up national freight and passenger markets, external to cross-border competition.

There are rules stating that the track and rolling stock must be managed separately - an attempt to allow free competition, although state-owned railways across the continent use holding companies in order to abide by this. A new European Commission strategy - the Fourth Railway package - to be voted on this summer by the European parliament could further pressure member states to open state-owned railways to private competition.

None of these hurdles are insurmountable, says Ian Taylor, author of Rebuilding Rail, a 2012 report for the trade unions. "The biggest obstacle to renationalising the railways is the prevailing dogma - the assumption that marketisation and competition must be best."

So what do the political parties say? Labour's official policy is to allow the state to bid for franchises. But in recent weeks new shadow transport secretary Michael Dugher has gone further.

"The public sector will be running sections of our rail network as soon as we can do that," he told the New Statesman recently. He ruled out a return to British Rail but said a Labour government would put "the whole franchising system as it stands today in the bin".

The Conservatives are against nationalising the network. A spokesman says that franchising has led to the most improved railways in the EU with record levels of investment, passenger numbers doubling and punctuality rates at record levels. The state ownership of East Coast main line shows that, he argues.

"While most operators spend more per journey than they get from passengers, East Coast hasn't. East Coast charged passengers on average more per journey, while running older, cheaper trains than on the privately run West Coast line. The new East Coast franchise will turn that round, bringing new services, new investment, more seats, state-of-the-art new trains and faster journeys - and it will return more to the taxpayer too."

The line about operators spending more per journey is another sign of how complicated railway funding is. Train companies do not just receive money from fares, some also receive direct public subsidy.

Nationalisation of the railways

Britain's rail system began as a series of local rail links operated by many small private companies

The Liverpool to Manchester Railway, completed in 1830, was the first successful railway line to open in Britain

The Railways Act 1921 saw the companies grouped into the 'big four' - Great Western Railway, the London and North Eastern Railway, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway and the Southern Railway

The railways were often targeted by German bombers during World War II

The 'big four' were nationalised to form British Railways in 1948 by the then Labour prime minister Clement Attlee

The Liberal Democrats are opposed to full nationalisation, arguing it would cost too much. But the current anomaly, whereby public sector rail operators from abroad can win franchises here while UK public sector operators cannot, should be ended, says a spokeswoman. Dugher's recent comments shows that Labour is shifting towards nationalising the network, the Lib Dems argue.

UKIP transport spokeswoman Jill Seymour says the party is not against state-owned companies bidding for a franchise: "Just look at how successful the East Coast main line has been, making a profit and returning the cash to the Treasury." However the party opposes full nationalisation. "There are currently plans to invest in rail lines up and down the UK from private companies, and the threat of nationalisation could put this investment at risk."

The Green Party is committed to full nationalisation. "Over time the Green Party would return the railways to public ownership to secure a cheaper and better service," a party spokesperson says. "As franchises expire, they would be re-allocated to a public body nominated by the secretary of state."

Plaid Cymru wants to see a devolved railway in Wales with "as much public control as possible". Rail franchising in Wales has already been devolved and now discussions are taking place over infrastructure, it says. "Our priority is that no profits should be taken out of the network in the form of dividends."

The Scottish National Party is not explicit about where it stands on rail nationalisation. But it attacks the restriction on public bodies bidding for franchises. A party spokesman says it has asked three UK secretaries of state to have the law changed and each time been refused.

The 'Inter-City Girls' were employed by British Rail to deal with passenger enquiries in 1968

Free market advocates argue that the Railways Act did not deliver enough privatisation. They say since Railtrack was brought back into public hands to become Network Rail the railways have been a strange hybrid of state and private sector.

The rail industry's problems are the result of government interference, argues free market think tank the Institute of Economic Affairs. "The last thing the sector needs is even more political meddling, but that is exactly what nationalisation would entail," says Dr Richard Wellings, the institute's head of transport. He advocates selling off Network Rail and removing the separation between track ownership and train operation.

Even opponents of privatisation, such as rail writer Christian Wolmar, agree that the Railway Act led to a messy sector that is not really truly privatised. "As one railway manager who used to work for British Rail and then spent 20 years with a private operator, never tires of telling me 'the Department has far more involvement in the day to day running of the railways than it ever did in the days of BR,'" Wolmar wrote, external.

Supporters argue that this messy system is delivering. Since privatisation, passenger journeys have shot up, external from 761 million passengers in 1995/96 to 1.58 billion in 2013/14.

Passenger statistics are doing well in comparison with Europe too. Since 2008 the UK has seen a 17% growth in passenger kilometres, the second highest behind Austria.

Rail services around the world

Canada - nationalised, run by VIA Rail Canada, though many of the train lines used are owned by private freight companies

France - nationalised, run by SNCF

Germany - nationalised, Deutsche Bahn, but regional transport authorities are responsible for tendering local train services

Italy - nationalised, run by Trenitalia, but runs on a similar local level as Germany

Japan - mainly privately owned, though the high-speed Shinkansen lines and some smaller lines are still publicly-funded

US - passenger services state run by Amtrak, but it operates in part on privately-owned train lines

On the other hand, subsidy has grown. A 2013 report, external for the Transport Select Committee stated: "Although the level of government support has varied from year to year, in general it has increased from around £2.75bn (in 2011-12 prices) in the late 1980s to £4bn today." Some say, external this is a conservative estimate.

Commuter fares are higher than in Europe and have risen faster than inflation, external in many years as successive governments attempt to push the cost burden from central government to rail users.

Some unregulated fares - especially advance tickets - are cheaper, but many in peak time have risen more, external than the cost of inflation.

Advocates for nationalisation like Taylor say the fragmented network wastes about £1.2bn a year. This is what it costs to have separate franchises "interfacing" with each other and Network Rail, and the profit "leakage" to shareholders of dividends, he says. Then there is the inconvenience factor.

Since privatisation it has become almost impossible to do triangular journeys, Taylor says, without complicated batches of single tickets.

The Rail Delivery Group rejects the £1.2bn figure. It includes money paid to rolling stock companies to lease trains and the cost of Network Rail using private contractors, something even British Rail did, a spokesman says.

And the "interfacing" between different franchisees is not just a cost but a benefit, he argues. "This interfacing is all about a system which is designed to encourage better performance [punctuality] among Network Rail and train operators."

The privatised railway's financial structure can seem like a jigsaw puzzle of subsidy, track charges, money returned to the taxpayer, and money paid to shareholders.

But Mark Smith says the argument over ownership is a red herring. "What you need is good management." The UK's railways are a success story and it would be a mistake to spend millions of pounds undoing the franchise system, he argues.

The unions say that the increase in passenger numbers correlates with GDP rather than better performance by train operators. It seems certain they will continue to fight for a change.

More from the Magazine

The wheels of rail privatisation were set in motion in January 1993, when John Major's government enacted the British Coal and British Rail (Transfer Proposals) Act 1993. At the time, the message was that fares would rise no faster under the new privatised railway than under British Rail. It was suggested that they might even fall. So two decades on, what has happened?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.