Singapore at 50: From swamp to skyscrapers

- Published

Fifty years ago Singapore became an independent state, after leaving the short-lived Malaysian Federation. With no natural resources, just how did this tiny country go from swamp to one of the region's leading economies? On the strength of its human resources - immigrants like my grandfather.

At the age of 17, with only the shirt on his back, Fauja Singh left his parents in a small Punjabi village and made the long and dusty journey on foot and by train to Kolkata (Calcutta), where he caught a ship to his new home. It was the early 1930s.

He arrived in a melting pot of cultures and chaos on an island at the mouth of a river, which bustled with trade - Singapore.

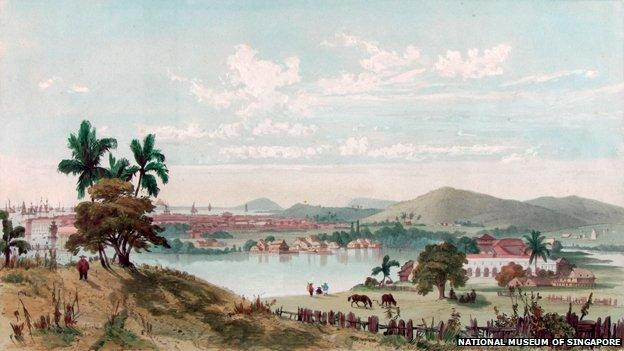

Once a swamp-filled jungle, when the British arrived in 1819, under the leadership of Sir Stamford Raffles, the makings of modern Singapore began. Lying at the mid-point of the shipping route between India and China, it became a thriving trading port, and with this trade came a huge influx of immigrants from all over Asia.

Life was not easy for the new arrivals. Many from China worked as labourers and lived in squalid and cramped conditions. Fauja worked in jobs ranging from night watchman to milk vendor and moneylender. When he had made enough money he went home to fetch his brother, sister and young bride from Amritsar.

Immigrants poured in from the southern coasts of China and the Malay archipelago

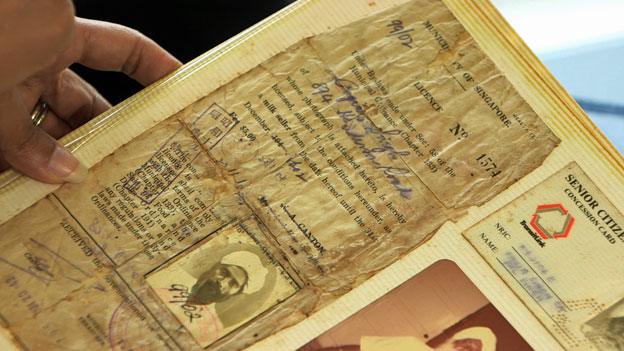

Fauja Singh's milk vending licence

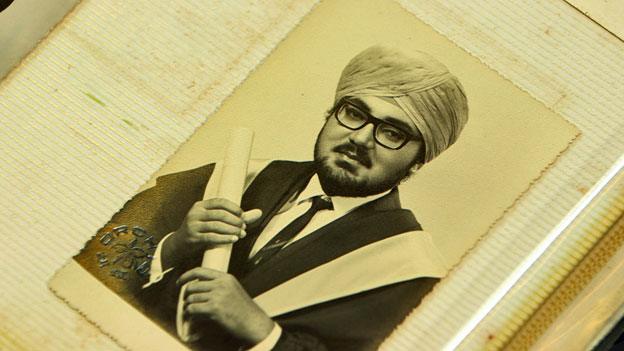

Fauja and his wife Swaran Kaur had eight children. His eldest son Kernail excelled academically and made it to the country's most prestigious school, Raffles Institution. He went on to win scholarships at university and after graduating he joined the government of a young and newly independent nation.

Fauja Singh was my grandfather, and Kernail my father. They paved the way for me to be educated and well-off. It's a story that echoes that of many Singaporeans, and also of the nation itself.

Singaporeans are among the world's wealthiest populations - Ferraris and Rolls Royces are a common sight on the clean streets. It's a far cry from the island's humble beginnings, when more than a million Singaporeans lived in "squatters" - makeshift wooden houses in villages known by the Malay term "kampongs".

My father and his siblings grew up on a large plot of land that sits in current-day Bukit Merah, an area in central Singapore whose name means "Red Hill". My grandfather claimed the land by planting a perimeter of banana trees which formed dense foliage and kept others out. Then he built a house so large, he would later rent out its back rooms to lodgers. But the house, like many at the time, was rudimentary.

My aunt, Manjit Kaur, was born there in pre-independence Singapore. "It was a hard life. There was no water, no healthy water," she says. "We lived a simple life, our neighbours were simple. We looked after each other and we had the same goal - to survive."

The Singh children in the kampong

In 1959, Britain took the first steps toward granting independence by allowing Singapore to govern itself. The charismatic Lee Kuan Yew of the People's Action Party won a landslide victory in the first fully elected parliament.

Manjit remembers the family attended a political rally, despite not speaking the language. "We didn't understand a word but I think whatever he was saying must have been quite important because everyone was paying attention. They clapped every time he would say something. When they clapped, we clapped," she says.

This was a revelation to me - I had no idea my grandfather had had any interest in politics.

My aunt Manjit Kaur shows me her photo album

My father Kernail in his 1968 graduation photograph

In August 1963, Singapore joined the Federation of Malaysia. It was made up of four countries and territories - Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore.

Manjit remembers celebrating the union at school. "We started learning a song called something like Let's Get Together, Sing a Happy Song, Malaysia Forever."

But it wasn't forever. The members of the federation disagreed on fundamental issues like who should control the finances of Singapore. Racial tensions led to riots between Singaporean Chinese and Malay groups.

Members of the Singapore Police Riot Squad during race riots between Chinese and Malay groups in 1964

In 1965, Singapore was forced to leave the Malaysian Federation. Manjit remembers seeing the prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, cry during an interview. "We'd go to our neighbours' house and watch TV and we saw him crying and we didn't know why."

It was a traumatic beginning to independence. Many believed Singapore could not survive on its own. But with huge hopes for the future, Singapore began to build the infrastructure that would transform the city.

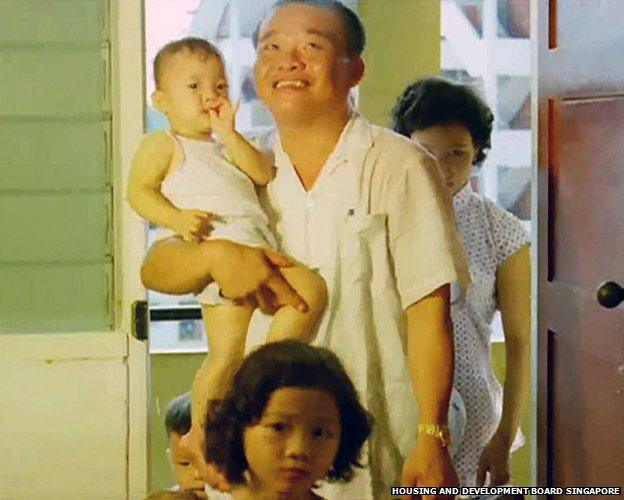

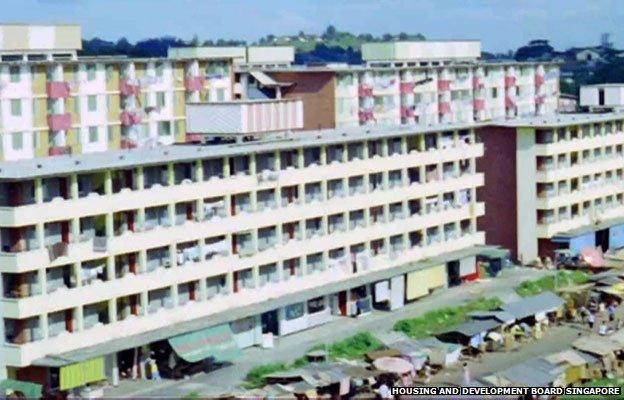

My grandfather sold his plot of land to the government in the 1960s and moved into a HDB or Housing Development Board home, thousands of which were sprouting up all over the island. It was an affordable way for Singaporeans to buy property and raise their standard of living.

Happy Homes poster showing the benefits of a Housing Development Board home

"We had a huge task when we first started in 1960. At that time our population size was 1.6 million, out of that, 1.3 million lived in squatters - not to count thousands of others living in slum areas and old buildings," says Liu Thai Ker, who was known as Singapore's "master planner" in the 70s and 80s. The new HDB towns that Liu oversaw came with their own schools, shops and clinics. The high-rise buildings introduced many Singaporeans to the miracles of flushing toilets and clean water at the turn of a tap.

A typical kampong scene

Like many Singaporeans, Fauja Singh swapped his "squatter" for a HDB home

By 1985, in just one generation, Liu says, the HDB was so successful in its rehousing policy that Singapore could claim to have "no homeless, no squatters, no poverty ghettos and no ethnic enclaves".

Courtesy mascot Singha the Lion

But the housing policy was not just about bricks and mortar - it was also about nation building. Each HDB flat would have a quota system that encouraged a mix of different races. "The whole idea was to have the Chinese not thinking that they were Chinese, or the Malays thinking they're Malay, or Indians thinking they're Indian. We want them to think as one Singaporean," says Liu.

Nation building also took the form of campaigns to instil more courtesy, prevent spitting in public or stop creating "killer litter" - rubbish thrown out of high-rise flats that could kill people below. These campaigns, external dominated the airwaves, schools and billboards of the nation.

The government sought to regulate the behaviour of its people and I was not immune. As a child attending a Singaporean primary school I won the title of most courteous student in class several times. My reward was a Singha the Lion eraser or ruler. He was the country's courtesy mascot for years.

Some of the campaigns were arguably too successful, such as the "Stop at two" campaign, aimed at limiting population growth in the 1960s and 1970s. When it became evident that Singapore's population wasn't being replaced in the 1980s, it was too late. Singapore now has one of the lowest birth rates in Asia, which the government is seeking to offset through immigration. For a population to remain stable each family needs to have 2.1 children - in Singapore the average is 1.3 or below.

A poster in a shopping mall encouraging Singaporeans to have more children

Such campaigns were more than just slogans - they had policies to back them up. Third children were penalised with fewer subsidies and limited school choices.

By the 1980s, many of Singapore's early problems had been solved. Unemployment was no longer a worry, crime rates were low, and the population compliant.

But at what price? The measures the government took to maintain the status quo are seen by many as controlling and restrictive.

The penal system is tough, and the death penalty is enforced, mostly for drug offences. It is estimated that abound 400 people have been hanged since 1991. Singapore has been described as "Disneyland with the death penalty."

Goh Chok Tong, who was Singapore's prime minister from 1990 to 2004 and now holds the title emeritus senior minister, takes issue with that description. "First of all, Singapore is not Disneyland, it's a very serious place. Then the death penalty, because of the proximity to the drug triangle, if we're too lax in the control of drug trafficking, Singaporeans are going to suffer. So it's a difficult decision, but we have to defend our position on that," he says.

Goh Chok Tong, Singapore's second prime minister, remembers growing up

Singapore's media environment is highly controlled. The nation currently ranks in the bottom 15% of 180 countries in an index assessing press freedoms compiled by Reporters Without Borders.

Singaporeans with an alternative view on political matters have now turned to the internet - Ariffin Sha, a 17-year-old blogger says the internet is the "game changer", dispelling the fears Singaporeans used to harbour over speaking out.

"I believe there was a climate of fear in Singapore, and I don't blame them. Dissent was clearly not tolerated. Times have changed now. With the internet it's hard to control," says Sha. At Speaker's Corner, the only officially sanctioned area of protest, 500 people might hear him speak - whereas on YouTube he has an audience of thousands.

The arts battle censorship too - playwrights have to submit scripts to Singapore's Media Development Authority who may insist on changing lines or put an advisory on the play. "When we first started working in the 80s we had to submit scripts to the police," says Haresh Sharma, a prominent name in Singapore's theatre community. "Now it's a bit more sophisticated. They might give you a rating but then people are free to choose."

Three Singaporean theatre directors discuss censorship

Goh says there are certain areas in the media where control will continue to be exercised.

"Religions, race… if you touch on sensitive issues there will be violent reactions so those are no-nos. The government has to make sure people don't infringe on these."

After years of rapid growth and ranked the most expensive city in the world by the Economist Intelligence Unit, Singapore faces new challenges. The gap between rich and poor is amongst the widest in the developed world. Estimates from social researchers suggest that about 10% to 15% of the population live in the low income bracket - less than US$1,100 (£700) a month.

Ferraris are common on the streets of Singapore - but the gap between rich and poor is growing

If my grandfather arrived today, with only the shirt on his back, how would he fare? He might not be as welcome. Foreigners now make up 40% of the population and the huge rise in their numbers in the last decade has sparked fears that the Singaporean identity is being diluted.

Jim Rogers is a businessman who moved to Singapore at a time when it was eager to attract well-qualified foreigners. He's aware of the backlash. "You'll hear people talking about the foreigners, and I say: 'Wait a minute you're second generation - your parents came here.' And they'll say: 'Yeah, but it was different. My parents were different to these new immigrants who are coming here now.'"

The government has responded with stricter rules limiting the influx of immigrants, but Rogers hopes they remember Singapore's success was built on them.

At the same time, people are leaving - the high cost of living and the search for a better work-life balance has led many to move away. In a 2012 survey, 56% of the 2000-odd Singaporeans surveyed said they would migrate if given a choice.

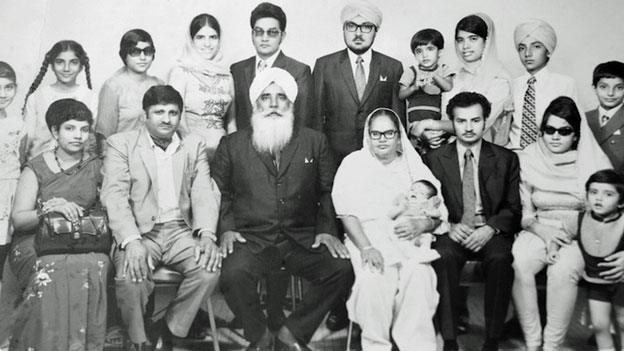

Fauja Singh's family in 1970 - only three grandchildren remain in Singapore

This too is reflected in my own family. My two brothers and their children now live in the US and my mother joined them there after my father passed away. The majority of my grandfather's huge family, captured in a photograph in 1970, no longer live in Singapore. Only three of his 15 grandchildren still do. I chose to return after many years away in the US, Canada and Japan. What made me come back? The same reasons my grandfather came - opportunity.

Where our leafy family home once stood there is now a big grey industrial complex. But growing up in a country where things are constantly changing, you don't expect things to last. There is always a steadfast march towards progress.

Watch A Richer World: Singapore at 50 on BBC World News on Sat 28 Feb at 09:10 GMT and 20:10 GMT, or Sun 1 Mar at 02:10 GMT and 15:10 GMT.

For more on the BBC's A Richer World, go to www.bbc.com/richerworld - or join the discussion on Twitter #BBCRicherWorld, external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.