Surviving Iwo Jima

- Published

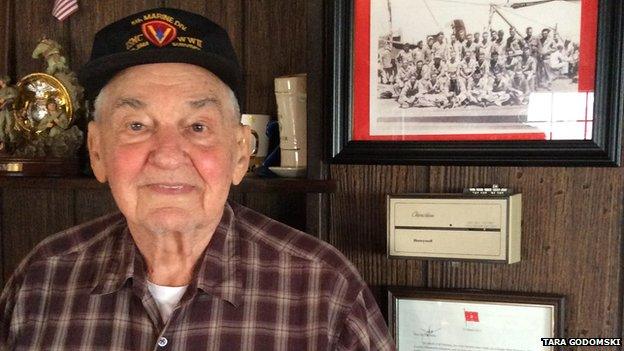

On 19 February 1945 the US launched a land invasion of the heavily defended Japanese island of Iwo Jima. It was the start of one of the hardest-fought battles of the World War Two. John Laurellio was among the US marines who spearheaded the assault 70 years ago.

"I was in the first wave that landed. And I'm here to tell you - there was action. There's just chaos on the beach when you first get there."

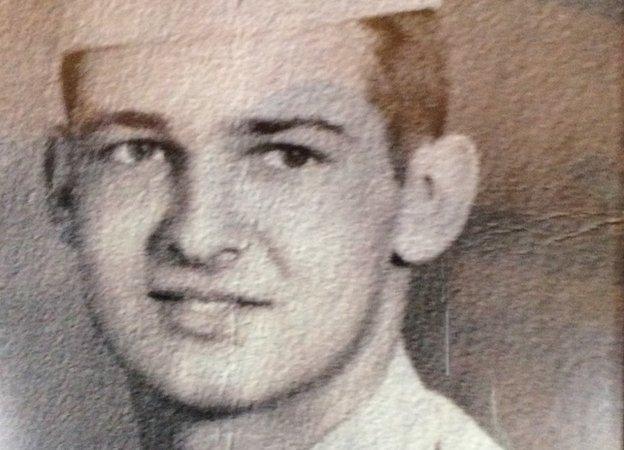

Laurellio was a 21-year-old corporal in the 5th US marine division when his regiment became one of the first American units to land on Iwo Jima.

"It was death from the sky," says Laurellio. "You were here one minute, and the next you were talking to the angels. And people right in front of you would just disappear. They got hit with a direct shell and just vaporised."

The Japanese were well prepared to defend the island.

"To our left was a 550ft (168m) volcano," Laurellio recalls. "To our right was sheer cliffs of rock. And from both of those points they were firing machine guns. The sky was just full of tracers, and for every tracer you could see there was a black shell in between.

"They were dropping these artillery shells down and they were showering their shrapnel on us."

The marines were also facing snipers and mortars as they attempted to get off the beach, and they were soon taking heavy casualties.

"There was a little bit of flat sand where we actually came off the ramp of the (landing) craft, and almost immediately there was this first terrace that went up and levelled off at about 18ft (5.5m), and then there was another terrace like that.

"You had to get up both of those before you got on to the flat land. And all that entitled you to is to get shot at more than you did on the other part of the beach."

Iwo Jima was of vital importance to both the Americans and the Japanese.

Japanese fighter planes used the island as an airbase, and it was a staging post for attacks on US forces in the Pacific.

But with three airfields, the US could also use the captured island to launch attacks on the main islands of Japan.

Tens of thousands of US marines faced more than 20,000 well prepared Japanese soldiers dug into the island's inhospitable volcanic rock.

"They were in 50-gallon oil drums sunken into the ground with a camouflaged lid," explains Laurellio.

"You honestly couldn't see them, they were masters of camouflage, and they had smokeless powder, so when they fired at you, you saw nothing. All you could hear was the thing whistling by you if they missed you.

"As soon as you put your head up it got shot off. And you didn't know where the shot came from."

John Laurellio's unit gradually wrested control of the airstrips, while another marine unit overran Japanese positions on Mount Suribachi, which commanded the southern end of the island.

The photograph of a group of US servicemen crowded around the American flag on the mountain top was to become the iconic image of this battle, and of the whole war in the Pacific.

But even after taking Mount Suribachi the Americans still had a long way to go to fully conquer the island.

One of the soldiers who raised the stars and stripes later joined Laurellio's unit.

"He was standing there and all of a sudden a piece of shrapnel came down from the sky, and ripped him wide open," Laurellio recalls.

"He was alive long enough to say, 'They've killed me.' And sure enough he was right."

It would take until late March for the American forces to secure control of the island. The five-week battle for Iwo Jima would inflict heavy casualties on both sides. Almost 7,000 US personnel lost their lives, and the fighting left many more injured. Most of the Japanese troops on the island were killed.

"Somebody said the Japanese were not 'on' Iwo Jima, they were 'in' Iwo Jima," says Laurellio. "Some of their living quarters and storage areas were four storeys below the surface. That's what made it tough."

After 37 days on the front line Lauriello's unit was withdrawn from the island to rest - and to prepare for battles yet to come.

"All I can say is it was not a pleasant experience. It was fine to survive. It's something you wouldn't sell for a million bucks but you'd never do it again."

John Laurellio spoke to Witness on the BBC World Service. Listen again on iPlayer or get the Witness podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.