America's 50-year journey from Bloody Sunday in Selma

- Published

A 17-year-old civil rights demonstrator is attacked by a police dog in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963

Of all the battles of the civil rights era, few have been lodged quite so firmly in the American memory as "Bloody Sunday" in Selma, Alabama.

On one side of the racial divide was that brave column of protesters, two abreast and smartly dressed, who knew they could end the day as martyrs.

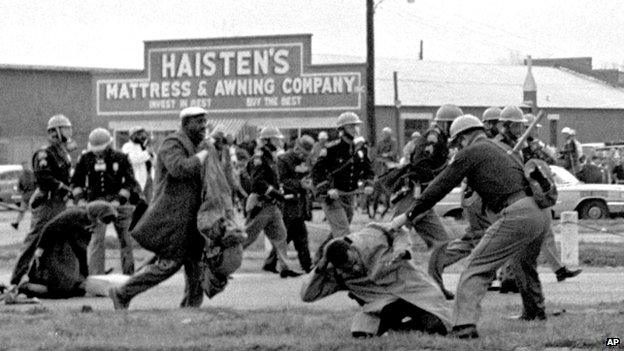

On the other was the Alabama state troopers, helmeted and holstered, carrying truncheons and wearing gas masks, who were eager to play the brutal role assigned them by history.

Brute force

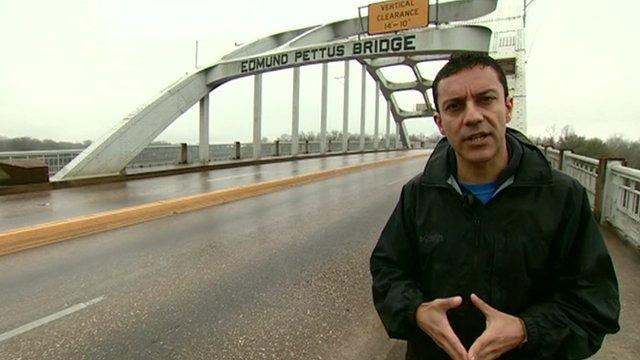

They faced off on what became a great landmark of the freedom struggle, the Edmund Pettus Bridge - a stark, geometrical structure that provided an eerie setting for this climactic showdown.

The soundtrack came from the chants of the movement and the anthems of determined hope: "Ain't gonna let nobody turn me 'round." But it was the brute force of that day, shrouded though it was in dense clouds of tear gas, which lingers most powerfully in the mind.

Fifty years on, those violent images still have the capacity to shock and shame. The blows from those truncheons. The charging police horses, with their trampling hooves. The bloodied bandages. The broken bones. The fractured skulls.

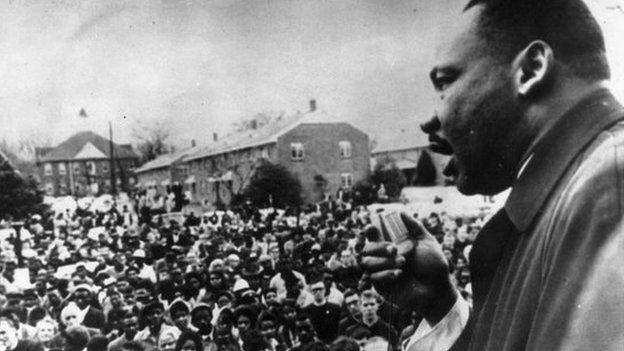

Martin Luther King called Bloody Sunday "the greatest confrontation so far in the South"

More so than the courage of the protesters, however, it was the viciousness of police that turned Selma into such a milestone.

Martin Luther King, who was in Atlanta on Bloody Sunday but soon travelled to Alabama, called it "the greatest confrontation so far in the South."

And it produced precisely the kind of violence that the non-violent black protesters relied upon to achieve major breakthroughs. Had it not been for police brutality, the civil rights movement would never have made such major strides.

Confederate central casting

Part of the reason why Selma had provided the ideal setting for such a historic showdown was because it was so easy to foretell the ferocious response of local and state police.

In Sheriff Jim Clark, black leaders had the perfect adversary. A former rancher, Clark had for years corralled black protesters seeking the right to vote with a cattle prod. A portly man, with a penchant for military regalia, his uniform was emblazoned not just with the six-pointed sheriff's star but a badge proclaiming "Never." A son of Dixie, he seemed to have stepped from Confederate central casting.

On Bloody Sunday, Clark's posse of officers had meted out some of the most violent beatings, with the sheriff in the vanguard. But the civil rights movement, for all the blows and its injuries that its members sustained that day, needed him to be there, because he personified southern intransigence. Had the march passed off peaceably, there would be no cause for commemoration.

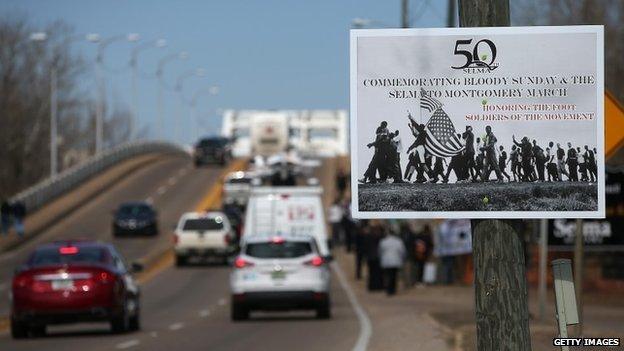

The communities in Selma and Montgomery are preparing to mark the historic civil rights marches

As it was, the bloodshed in Selma prompted President Lyndon Baines Johnson to push for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, one of the most significant pieces of legislation ever passed by Congress. As a writer for the New Republic observed at the time, "Selma's Sheriff Jim Clark can take much of the credit for the bill."

Eight days after Bloody Sunday, LBJ also delivered perhaps the greatest presidential speech on race relations, in front of a joint session of Congress and a primetime audience of 70 million viewers.

"At times history and life meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom," he intoned, in his Texan drawl.

"So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama."

Then, in a dramatic rhetorical end-piece that aligned him with the foot-soldiers of the struggle for black equality, he told Congress: "We shall overcome."

Creative tension

Two years earlier, in Birmingham, Alabama, non-violent protests had also produced a violent rejoinder from police.

The police's German Shepherd dogs snarled and lunged at black protesters, tearing their clothes and ripping their skin. High-pressure fire hoses, with the power to rip bark from trees, were trained on children.

Civil rights marchers flee from Alabama state troopers in Selma on 7 March 1965

As with Selma, this was the intention of black leaders all along: to orchestrate protests that would provoke such a vicious response that it would prick the conscience of white America and pressure a reluctant president, in this case John F. Kennedy, to act.

As he languished in one of the city's cells, King laid out this strategy in his famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

"Non-violent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension," he wrote on scraps of paper, "that a community that has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue."

Gestapo-like methods

Like Selma, Birmingham threw up a model adversary, the grandly named Theophilus Eugene Connor, who was better known as "Bull". In the country's most thoroughly segregated city, police used what King described as "Gestapo-like methods".

Way in advance of the militarisation of American police forces, an armoured personnel carrier already patrolled the streets of the city, called "Bull Connor's tank".

Mounted in the spring of 1963, the Birmingham campaign was pivotal.

Not only did the ugly images of police brutality build white support for an end to southern segregation, but they unleashed a wave of black fury that deeply unsettled the Kennedy brothers in Washington.

National Guardsmen were sent into Alabama by President Lyndon B Johnson in 1965

Between May and late August of 1963, there were 1,340 demonstrations in over 200 cities across 36 states. Fearing that his presidency could be overwhelmed by the great social revolution of his age, Kennedy finally agreed to send a meaningful civil rights bill to Congress.

In June 1963, he also delivered a long overdue televised address to the nation in support of desegregation.

"We are confronted primarily with a moral issue," he said from the Oval Office. "It is as old as the scriptures and it is as clear as the American constitution."

Need for thugs

Had it not been for Bull Connor and those snarling police dogs, Kennedy, a bystander on civil rights for so much of his presidency, might have remained on the sidelines.

When the president hosted his first summit of civil rights leaders at the White House that same month, he even acknowledged the Alabaman's role. "You may be too hard on Bull Connor," he said.

"After all, Bull has probably done more for civil rights than anyone else." At first there were sharp intakes of breath, until they realised that Kennedy was joking. But it was only a half-joke. The civil rights movement needed thugs like Bull Connor.

Without him the 1964 Civil Rights Act might never have been enacted.

Police brutality in Alabama unleashed a wave of black fury that deeply unsettled US politics

Long forgotten now is the failed Albany campaign in 1962, where King's leadership of the civil rights movement - a broad amalgam of often antagonistic groups - was brought into question.

King's great misfortune in Albany was to come up against a police chief who understood the strategy of creative tension. Laurie Pritchett had studied Gandhian principles of non-violence and how protesters would apply them in this Georgian backwater.

Throughout the demonstrations, then, his police force was a model of restraint and calm. King suffered an embarrassing defeat.

National reckoning

In the decades since, the catalyst for many of the most meaningful national conversations about race relations, and many of the moments of national reckoning, have been acts of police brutality or failures of the criminal justice system.

The merciless beating of Rodney King by cops from the Los Angeles Police Department in 1991, and the deadly riots a year later that followed the acquittal of the officers involved, prompted major police reforms.

Lifetime terms for LAPD police chiefs came to an end. This led to the creation of an independent inspector of police. A new emphasis came to be placed on community policing, not just in Los Angeles but across the country.

The death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, last year provoked national introspection

To this day, Barack Obama, the first black man to occupy the White House, tends to discuss race mainly in the context of police excess or criminal justice.

The controversy in 2009 surrounding the arrest of the black Harvard academic Henry Louis Gates prompted his strongest racial remarks since taking office.

By arresting Professor Gates as he tried to enter his own home, the Cambridge police had "acted stupidly", the president complained, adding: "there's a long history in this country of African Americans and Latinos being stopped by law enforcement disproportionately".

The killing of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old shot dead by a neighbourhood watch volunteer in Florida, prompted another presidential intervention.

"My main message is to the parents of Trayvon Martin. You know, if I had a son, he'd look like Trayvon," Obama said.

"All of us as Americans are going to take this with the seriousness it deserves."

'Selma is now'

The deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York, both at the hands of police officers, have more recently been the spur for national introspection and protest. Both bridge a contemporary edge to this weekend's commemorations, and with it the sense that many race-related issues remain unsolved.

That is why when the singer-songwriter John Legend proclaimed that "Selma is now" from the stage of the Academy Awards in Hollywood, as he picked up the Oscar for his song Glory from the movie Selma. It had such resonance.

Manifestly, race relations in America have come a long way since Bloody Sunday, when a system of racial apartheid was still in the process of being dismantled in the south, when citadels of segregation, like Selma and Birmingham, finally surrendered.

But not every wall of prejudice has been demolished.

- Published2 March 2015

- Published4 March 2015

- Published5 March 2015