France holds back the anti-smacking tide

- Published

A Council of Europe ruling that French laws on smacking children are not sufficiently clear, binding or precise, has ignited a national debate in a country where a parent's right to discipline children is still held dear.

Turn on the radio in France in 1951 and you might have heard contributors extol the benefits of parents smacking their children.

"I don't like slapping the face," one commentator says. "Slapping can harm the ears and the eyes, especially if it's violent. But everybody knows that smacking the bottom is excellent for the circulation of the blood."

At the time, few would have seen that advice as abusive. It was another three decades before Sweden became the first European country to make smacking children illegal. More than 20 others have followed suit, but France has held out against the changing tide of parenting, with staunch resolve.

In the wake of the European ruling this week, articles have appeared in the French media with titles such as "Smacking: A French Passion", and contributors have lined up on online forums to advocate the benefits of "la fessee", as it's known here.

"We were really surprised by the response," says Christine Hernandez, a writer for France's most popular parenting magazine, Parents.

"Many of our readers said that smacking is part of educating children. It's astonishing that parents still think that it's a good way to teach children how to behave. They think they have to impose their authority on children from time to time - it's part of French traditional upbringing."

Like other European states, France criminalises violence against children, but it also allows parents the right to discipline their children at a low level. What constitutes low-level discipline, and what constitutes criminal violence, is left to the courts to decide - and often sparks controversy.

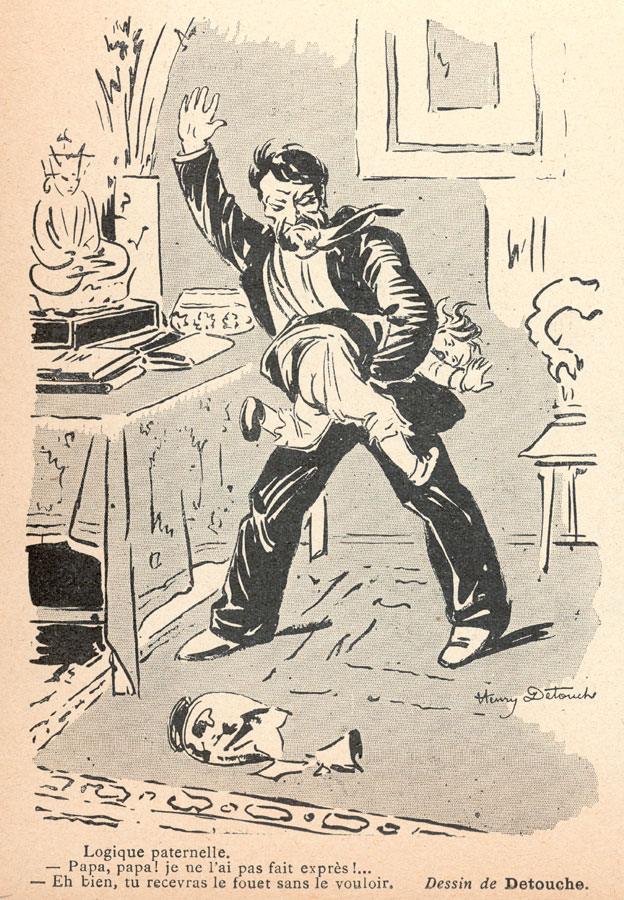

Paternal logic: "Papa, papa, I didn't mean to do it!" "Well then, you'll get spanked without wanting it." (1902)

In 2013, the courts decided that a father had gone too far in spanking his nine-year-old son, partly because he removed his son's clothes first. He was fined 500 euros, but the decision split the nation.

Childhood historian, Marie-France Morel, says that in centuries gone by, Catholic teaching and the State both emphasised the duty of French parents to bring up their children to be model citizens. "Parents had rights and duties," she says, "but children had only duties."

The French king Louis XIII was regularly beaten from the age of one, on the orders of his father, and when Sweden outlawed the practice in 1979, she says, the French found it funny.

But attitudes are changing, she says.

"There's been a complete change of environment when it comes to children," she explains. "With contraception, people started having fewer children, and most babies are wanted by their parents. There's a new perception about the rights of the child."

Despite polls giving very similar results in both France and the UK when it comes to a legal ban on smacking - almost 69% were against it in the UK last year, against 67% in France in 2009 - the mood music around the issue can sometimes seem very different.

Comments on the British parenting website, Mumsnet, were almost uniformly opposed, with many readers describing it as "abhorrent", "bullying" and "inexcusable". "Does anyone smack their children anymore?" one asked. "And if so, is anyone brave enough to admit it, to explain why?"

That kind of horror and revulsion is much less part of the middle-class debate here.

Outside the Roquepine primary school in central Paris, parents have a range of views on the subject, but some are perfectly happy to stick up for smacking.

"It can't be a systematic thing," one father says. "But sometimes slapping is necessary for certain children to teach them limits. If you don't teach your child limits, they could do much worse things in the future."

A mother of two says she thinks "a light slap to make children understand" is fine, but that the European Court ruling was important, "because smacking could lead to abuse - even though I think the two things are different."

Only one mother is totally against la fessee: "I feel it degrades the parent in front of the child," she says. "It's horrifying."

Pamela Druckerman, author of Bringing up Bebe - about the French way of raising children to be well-behaved, unfussy eaters - says France is more socially conservative and has a "more traditional, authoritative style of parenting" than either the UK or the US, where her book has been a bestseller.

She sees both countries showing renewed interest in the French approach to parenting.

"I think there's a sense in the UK and elsewhere that the permissive, child-centred model of parenting has gone too far," she tells me.

But Even in France "you'd be hard-pressed to find an expert who was in favour of smacking".

2000: A child takes part in an anti-smacking demo at Downing Street

Over the last 50 years France has banned corporal punishment in schools, and a growing number of parents seem keen to avoid it. But this doesn't mean there would necessarily be support for a new law.

"French parents see a new law as insulting their ability to distinguish between a slap and child abuse," says Druckerman.

The Minister for the Family, Laurence Rossignol, meanwhile, told AFP that France didn't need a law, but a collective debate, adding: "I don't want to divide the country into two camps."

The Green Party tried last year to change the law to ban corporal punishment, but the initiative failed to get off the ground.

But Green MP Francois-Michel Lambert told the BBC that smacking was a "divisive question" and one that the government would most likely steer clear of while voters are "expecting results on the economy".

One reason why some people oppose a change to the law, commentators suggest, stems from their dislike of moralising or state interference.

Or maybe the government's moralising in the past worked too well.

"A bit of slapping never killed anyone," said one father waiting outside Roquepine primary school. "I was spanked as a child - it helped circulate the blood."

Perhaps his parents were listening to the radio in 1951?

Europe's smacking bans:

Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, FYR Macedonia, Malta, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine

Council of Europe: Progress towards prohibiting all corporal punishment, external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.