The longest detour

- Published

Badi had a good life in Damascus. But as the war in Syria closed in on his family, he took them to safety in Egypt and then set out for the UK. Two months later he was in a prison cell in Togo. His story illuminates a shadowy, corrupt network of migrant smugglers.

Badi woke up in a cheap hotel in Accra. He'd been in Ghana almost a month and his money was running out. For the tenth time that day he took out his mobile phone and called the smuggler. There was no answer.

A few days later he got a call. The smuggler said the plan had changed, that he should get in a taxi and go to Togo.

"We thought Togo was a neighbourhood of Accra, or maybe another town just down the road," says Badi. "So we got in the taxi. Turns out, Togo is a whole other country."

Life had been good in Syria before the war. He was a skilled tradesman who worked on construction sites all over Damascus. There was plenty of work - the family was not rich, but Badi had a house and a car, and his two little girls were thriving.

By the end of 2012, though, as the war intensified, work began to dry up and the fighting inched closer to Badi's home. "Every morning we looked out from the balcony and saw the skyline full of smoke. At night there was a lot of noise from the shells. I got used to it in the end, but my girls didn't. Every night they woke up terrified."

Together with his wife and the two girls, Badi took a taxi to Beirut and flew from there to Egypt. His brother was already settled in Cairo, but it soon became clear that this was not an easy place to raise children. There was no work and no prospect of finding any. Badi had brought his family to safety, but now he saw them sinking into poverty.

It was around this time that another of Badi's friends, a Syrian who had ended up in the UK, told him about a man who could get him into Europe.

Trusting his friend's advice, Badi wired $5,000 (£3,360) to a migrant smuggler called Abu Sami (not his real name), a Syrian who lived in Istanbul. It was money that Badi had borrowed from his family. From the moment he handed over the cash at a Western Union in Cairo, Badi was at the mercy of a man he'd never even met.

A few weeks later a different man, Abu Eyad, arrived in Cairo with another Syrian refugee, Huthaifah, and a couple of EU passports.

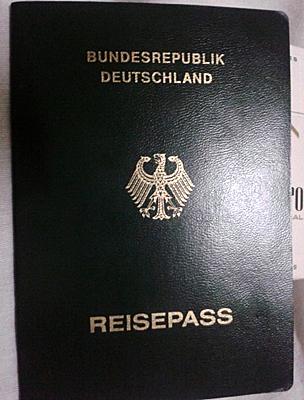

"They were German passports, totally fake, but at a glance they looked OK. They had our photos and new names, they even had stamps in them from Turkey and Egypt."

The passports, though, would not pass closer inspection. Abu Eyad told Badi and Huthaifah they would have to travel from a country where he had contacts, where the airport officials could be bribed into letting them go without asking too many questions.

The fake German passport given to Badi

At first he tried Sudan, but when that didn't work he settled on Ghana.

"It took seven-and-a-half hours to fly to Ghana," says Badi, "and that plane driver was putting his foot down."

In Accra, they were met at the airport by a uniformed Ghanaian official who led them straight into arrivals without going through passport control or getting an entry stamp. The official put them in a taxi and sent them to a hotel where they found Abu Eyad, the smuggler who they had first met in Cairo, fast asleep.

If Badi and Huthaifah hoped Abu Eyad might spring into action the next morning, they were wrong. While the two refugees waited and worried in the hotel, or tried to talk with their children on Skype, Abu Eyad slept all day and spent his nights drinking in the casinos and brothels of Accra.

"The problem," says Badi, "is that by that point you're already trapped. You've paid thousands of dollars to these guys, and you don't want to lose it. What could we do?"

What Badi and Huthaifah had to do, according to Abu Eyad, was go to Togo.

Having bribed their way across the border, the two men found themselves in the hands of a third smuggler - a Syrian who made Abu Eyad look like a model of hard work and integrity. "That guy couldn't say an honest word," says Badi. "He couldn't even tell you his name without lying, and he'd cheat you out of your last dollar. I swear, he was a dog."

Badi (right) with Huthaifah in Togo

After another month in Togo, Badi and Huthaifah realised they were on their own. They bought tickets to Egypt and tried their luck at the airport. They handed over their Syrian passports, told the truth about what had happened, and were promptly arrested and imprisoned.

"The mosquitoes in that jail were the worst I've ever seen," says Badi. Worse still was the fear that they'd never get out. After a week in prison in Lome, Badi and Huthaifah were finally allowed to board a flight back to Egypt.

Between them, they'd given more than $20,000 (£13,460) to Abu Sami's gang of smugglers.

They were back at square one.

Badi and Huthaifah split up. Badi took a plane to Turkey and tried a different tactic. Instead of paying a single smuggler to get him into the UK, he would go country by country, relying on his own wits and on an informal network of Middle Eastern smugglers and refugees that has spread right across Europe.

The best of these men, Badi says, was the Syrian who showed him the way over a remote stretch of mountains into Greece. Badi paid 2,000 euros (£1,465, $2,175), walked all night on a smuggler's track through the hills, and then swam across a river, following an inflatable children's dinghy that was full of Syrians who could not swim at all.

In Athens, Badi handed over another 5,000 euros (£3,660, $5,440) to an Egyptian called Majdi, who arranged for a Greek lorry driver to smuggle Badi and two Syrian friends into Italy in the lorry's reserve fuel tank.

For 24 hours, the men struggled to breathe inside a burning hot metal box. The rubber lining on the floor of the tank melted, and what little air reached them was poisoned with exhaust fumes. But Badi doesn't blame the Egyptian, who he says was "a really friendly guy" and who at least delivered what he'd promised.

Badi at the flat where he stayed in Athens

Less affable was the Iraqi Kurd who, for another 500 euros, got Badi into a lorry in Dunkirk and through the Channel Tunnel into the UK.

"He was flashy, that guy. He dressed in sharp clothes, had an expensive watch, the latest iPad. He looked cool. But if you'd have crossed him, he would have cut your throat without a second thought."

Badi reached the UK in November 2013 and was granted asylum. The journey had taken 306 days and cost him 25,000 euros (£18,300, $27,200).

He settled close to a cousin in Bradford, where his wife and the two girls, Lina and Isra, finally joined him in December 2014.

It was for their sakes that he left his country, that he endured weeks in an African jail, that he swam across a river and was prepared to die inside a lorry's fuel tank. "I risked my future for theirs," he says.

He hopes the girls will be happy in the UK. They have now started primary school, and Badi is proud of their progress. "Isra has only been here for three months, and she's already translating for me," he says.

Badi himself is struggling to find work in Bradford, but remains optimistic. "We've been through some difficult times in Syria," he says "and it's taught us never to give up."

Where are Syrian migrants trying to go?

Huthaifah en route

Syrian refugees often enter the EU in Italy or Greece, but most would prefer to get to a country with more jobs and better social welfare. Police harassment can also be a problem.

The most popular countries are in northern Europe. The UK, the Netherlands, Germany, and the Scandinavian states are all seen as places that offer a degree of support to asylum seekers and provide migrants with a chance of finding work.

The United Nations estimates that migrant smuggling into the US and Europe earns smugglers more than $7bn (£4.72bn) per year. The real figure may be much higher.

The International Organization for Migration estimates that at least 4,077 migrants died in 2014 trying to reach a better life, and that at least 40,000 have died since 2000 - many of them at sea which is a cheaper but more risky way for migrants to travel.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.