IS looting provokes call for global response

- Published

Islamic State (IS) may have released images of destroying ancient artefacts, but sales of black market antiquities are likely benefitting the group

Looting and destruction of artefacts from ancient sites is rampant across Islamic State-controlled areas in Iraq and Syria, and there's little stopping traffickers from selling them to fund the militant group.

Authorities in New York this week have taken custody of more than $107m (£72m) worth of art thought to be looted from India and other parts of southern Asia.

The collection of 2,622 objects recovered from warehouses around the city is the biggest antiquities seizure in US history and is part of an investigation into an American art dealer awaiting trial in India.

The case is representative of how large-scale commercial looting is threatening cultural heritage around the world.

And experts say that laws to prevent the sale of stolen artefacts are wholly inadequate to deal with the crisis.

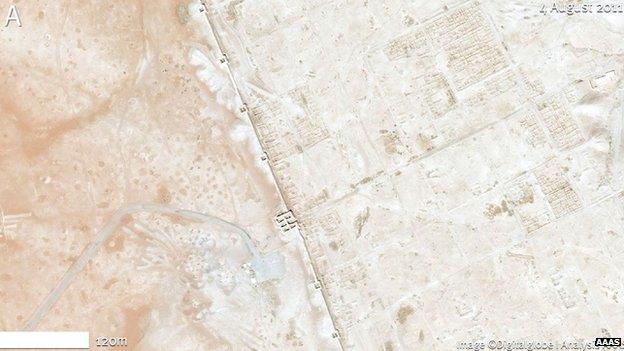

Looting holes now cover the ancient site of Dura-Europos in Syria (seen before in 2011, above) on the banks of the Euphrates (red circles indicate vehicles inside the site)

"The art market is very patient," says Tess Davis of the Antiquities Coalition, external.

"We know that dealers and some collectors are willing to wait years or decades until public attention has looked the other way before trying to slide these things in and introduce them to the market."

She studied looting patterns during Cambodia's eight-year civil war and says there are similarities to the pillaging under way in Syria and Iraq.

And she warns that trafficking may get even worse when the fighting stops.

"One of the big lessons we learned from Cambodia is that we have to be prepared for the post-conflict phase.

"As bad as the damage was during the war itself, once it was over, by no means did looting stop."

She says the trafficking networks who established themselves during the war thrived in peace time.

"I think that is something we have to be very prepared for in Iraq and Syria."

The illegal trade in Middle East is a major source of funding for Islamic State (IS), and pressure is mounting for a tougher global response.

A Sufi temple in Raqqa destroyed

Earlier this year the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution calling on countries to prohibit the trade in illegally removed cultural materials from Syria and Iraq.

And US lawmakers are looking at new measures to halt illegal imports to the US and stifle the flow of cash to IS.

But experts say the only way to prevent looting is to stigmatise the international market for antiquities - an approach that has helped animal rights organisations such as WildAid reduce poaching.

"As long as someone is willing to pay money for an antiquity and they don't care what the cost is to the country or to the people who live there and they don't care that their money will be supporting organised crime and perhaps terrorist organisations, there is going to be a trade," Davis says.

Iraqi archaeologist Dr Lamia Al-Gailani: "If you destroy it, you destroy your own history"

"Much like the demand for ivory, looting has to stop with the market."

Satellite images show that many historic sites in Syria are being ransacked almost daily. In the area surrounding the ancient ruins of Apamea, near Hama, looters dug more than 15,000 pits in one year.

"Apamea is famous, it's a World Heritage Site and I expected it to be the focus of looters," says Katharyn Hanson, an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Cultural Heritage Center.

"But looting is also happening at sites that nobody has ever heard of, that don't even have a name."

How much has been stolen is impossible to tell because objects illegally removed from the ground aren't documented. It could be decades before anybody even finds out they exist.

Katharyn Hanson in Iraq

Patty Gerstenblith, professor of law at DePaul University, says it's not enough to stop the object from reaching the market.

"You want to stop the whole smuggling enterprise and dismantle an international network of criminals who engage in money laundering and, we believe, support ISIS.

"That simply is not happening," Gerstenblith says.

"Even if an object is recovered and returned, that's a booby prize - it should be prevented from leaving the site in the first place."

There are a number of treaties and laws aimed at protecting cultural heritage - including the 1954 Hague Convention which the US ratified in 2009.

The 1970 Unesco convention was the first international treaty against looting and a special provision for Iraq was made in 2003.

But such agreements are difficult to enforce in times of crisis while the Hague Convention applies only to artefacts that are listed as part of a museum collection or similar institution.

Satellite imagery shows the destruction of Nebi Yunis in Mosul, Iraq, in less than two weeks

"The inability to respond quickly and effectively in situations that are true emergencies is definitely a major gap in the law," says Gerstenblith.

In March, Islamic State destroyed Nimrud, one of the most famous archaeological sites in Iraq dating to the 13th Century BC.

Unesco branded the attack a war crime and issued fresh condemnation this week.

And the AAAS Geospatial Technologies Project recently released satellite imagery confirming that Nebi Yunis, the tomb of the Prophet Jonah in Mosul, Iraq, was obliterated by Islamic State last year.

The group attempts to justify the destruction of such sites on the grounds that they are idolatrous.

But in both Nimrud and Mosul, any artefact that could be sold was reportedly removed first.

- Published10 July 2014

- Published6 March 2015

- Published21 May 2015