Why tennis 'courtsiding' was my dream job

- Published

Gamblers keen to get an edge over their rivals, have taken to employing "courtsiders", who send back live data to syndicates and betting companies while a game is under way. Last year a British man became the first person to be arrested while engaged in the practice, at the Australian Open tennis tournament.

For Dan Dobson it was a dream job. Still only 22 years old, he got to travel the world with some friends, earn a decent salary and watch top-level tennis.

He was not just a spectator though, he had to send back live data to the gambling syndicate he worked for, as each player scored a point.

To do this he used a simple device hidden inside his shorts.

"You would sit on court for as long as you were needed pressing the buttons, which were sewn into my trousers and relay the scores back to London. You'd press one for Djokovic, two for Murray, for example, as fast as you could," he says.

He is affable with the insouciance of youth and the confidence that comes with being well over six-foot tall, head-and-shoulders above most people.

Courtsiding is inextricably linked to "in-game" betting - gambling while an event is taking place.

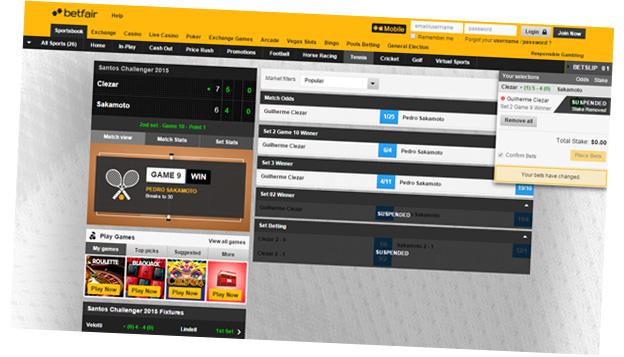

This betting happens on exchanges like Betfair, where gamblers pit themselves against one another, offering constantly changing odds on a player or team winning or losing, as a match progresses.

"The purpose of us being there is that we can send back information a lot faster than TV or betting companies can get the data," says Dobson.

That information would be fed back in milliseconds to the syndicate Dan worked for in London. It is based in a modest office storage block in Battersea, south London and run by Steve High, CEO of Sporting Data limited, which provides data and services to the syndicate he founded.

The syndicate designed betting software for tennis which works out the probability of each player winning the match at any point and how the odds are moving in real time on the betting exchange.

Steve showed me the kind of device Dan used, a modified game console controller.

"We had an automated system whereby the point data would come in and then we would cancel any bets that we had in the market that we deemed were at the wrong price," he says.

"And then we would place bets straight back into the market that we deemed were now the correct price."

The difference in getting that data first and changing the syndicate's betting position can be worth thousands of pounds per point, sometimes even tens of thousands, and there are a lot of points in a tennis match.

This has led many other syndicates to employ courtsiders. Steve High says he has been told reliably that 75 people were at last year's Wimbledon final, "sending information back or betting on their own".

He added: "The ones who were best at it, came up with the best odds and had the fastest data would have been the ones who made the lion's share of the money."

The All England Club, which runs the Wimbledon tournament, did not want to comment.

At the tournaments he went to in the Middle East, New Zealand and Australia, Dobson would recognise the courtsiders working for other syndicates or betting companies but he never talked to them. They were his rivals.

The tennis authorities have been trying to weed out courtsiders for years. Tennis umpires also provide official score data which is used by betting companies - and they don't want anyone else on their turf, getting valuable information from other sources.

The major tournaments like Wimbledon, and the Tennis Integrity Unit set up by the sport's governing bodies, employ spotters to try to find people like Dobson, who in turn do their best not to get caught.

"You get to know them because you'll see them looking around for you, and some of the [spotters] are the daughters and the sons of the umpires and so it's a bit of a game of cat and mouse," he says.

Dobson knew he was breaking the rules of his ticket, which was why he was hiding the device he was using to send back data. But he thought the worst that could happen to him, if caught, was that he would be thrown out.

But in January 2014 Dan Dobson's photo was in newspapers and websites across the world when he was the first person to be arrested while engaged in courtsiding.

A number of 'spotters' attend sporting events

It happened at the Australian Tennis Open in Melbourne, and this is the first time he has talked publicly about the incident.

"I was sat there all day on the same court in a 45-degree heat, pretty uncomfortable," he says.

"Towards the end of the day, I walked off court and a cop grabbed my arms, put them in a pair of handcuffs - and that was kind of when I knew something was up."

Dan was accused of trying to corrupt the betting outcome of a match, under legislation introduced by the state of Victoria, Australia's sporting capital.

If convicted, he faced a possible 10 years in jail, but as soon as the police started to question him, he felt it was clear they didn't understand what he was doing. "They thought I was having an impact on the integrity of the sport, having contact with the players, corrupting the sport in some way," he says. "But the truth is that's not what courtsiding is."

Although he had broken the terms of his ticket, courtsiding is not illegal and there was widespread criticism of the police's actions. Even supporters of tougher measures against courtsiders, like Chris Eaton director of sports integrity at the International Centre for Sports Security, thought the police had picked the wrong target.

"Courtsiding should be criminalised but the fact is it's a very minor issue compared to match-fixing and the corrupting of sports organisations in South-East Asia," he says.

The gambling syndicates operating in South-East Asia openly advertise for courtsiders, or scouts as they are also known, to work at football games in the UK and Europe.

The charges against Dobson were dropped but his career as a courtsider was shortlived. Following his arrest, Sporting Data limited got rid of the six courtsiders they employed - although they did keep on Dobson in a different role.

Would he go back to his old job? He smiles and says he would do it in a flash.

"I do feel, not hard done by, but it was a case of bad luck. I would have definitely carried on, it was an opportunity of a lifetime."

Does the House Always Win? was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday 21 April at 20.00 BST. You can catch up via the BBC iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.