The heist: What I've learned about the Hatton Garden raid

- Published

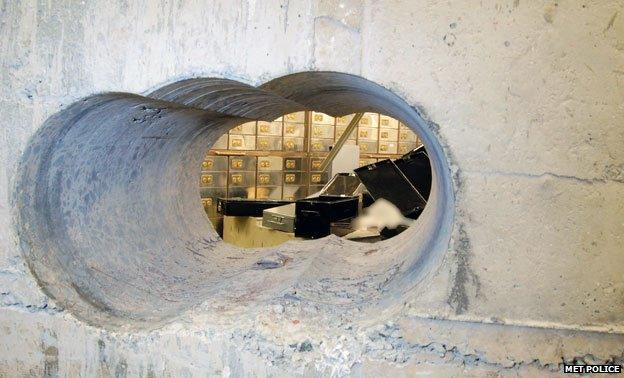

Seventy-two safe deposit boxes were opened in a raid in London's Hatton Garden over the Easter weekend. How did the thieves do it? Declan Lawn learned how to abseil, break locks and drill through concrete in an effort to retrace their steps.

Here's what I've learned: You can read all about the Hatton Garden Safety Deposit box raid. You can look at the pictures of the vault recently released by police, or the CCTV pictures of the burglars in action.

But until I was shown what it would physically take, I didn't realise just how many challenges - big and small - the thieves had to overcome.

Following the actions of the gang gave me insights into both the team who did it and the plan they were working to in ways that were surprising and often very telling. Perhaps it might even offer clues into the type of criminal organisation which carried out the heist.

Casing the target

It's a busy Tuesday morning in Hatton Garden, a perfect time to blend into the crowd. Former British Army surveillance operative Chris Regan, one of the best in the business, sets me a challenge - try to pick up as much information as I can from the streets around the building in order to understand how the thieves would have assessed the security.

Pretending to look in the windows of jewellers' shops, I get as close to the front door as I can. As people go in and out, I try to pick up as much information as I can about entrances, exits, and security measures.

It turns out to be remarkably difficult - the private security guards who patrol the streets notice me, and I can tell I am minutes away from being challenged. Added to that, I am constantly under CCTV cameras, and I have a general sense of sticking out like a sore thumb.

It isn't just because this is not long after the heist - Hatton Garden has always had a reputation for pervasive and effective street security.

"You stand out because you look like you're up to no good," Regan tells me. "You feel guilty and you look it."

He reckons the gang would have engineered a reason for being on the street when they needed to be, maybe handing out leaflets or doing a survey. If it was him, he says, and he had several months to plan it, he'd either get a job on the street or rent an office in the target building.

This was a job where the intelligence wasn't generated by opportunistic street surveillance, but by people who had exact information from the inside. On the night of the raid, there would have been surveillance on the street to give warnings about security guards.

The best way to do that, says Regan, is to rent either an office or a room in a flat overlooking the building several months before, and simply look out your own window while the crime is in progress. If he were the police, he'd be getting the rental records not just for every office in the building, but every viable place overlooking it.

Getting inside

It's still unclear as to how exactly the thieves got into the building.

They may have had someone inside the building simply waiting for the last person to leave, or could have gained access from adjoining rooftops.

One day last week - while the police investigation unfolded downstairs - I managed to talk my way in to the access laneway at the side of the building, the very place where the thieves were captured on CCTV.

If I could manage blagging access in 10 minutes flat, imagine what an organised gang could do over several months.

Descending the lift shaft

Attempting to abseil down a lift shaft

I'm not a fan of heights or enclosed spaces, and yet here I am, suspended on a rope attached to the bottom of a lift, swinging around in the dark.

On the plus side, I'm hanging beside a man who usually does this over Alpine ravines. Ian the abseiler gently talks me down, showing me how to release the clasp on the abseiling harness slowly and methodically so that I edge ever closer towards the bottom of the shaft.

Until I get there. That's when one phobia subtly cedes control to another. I'm at the bottom of a lift shaft, I suddenly realise. There's a door about a metre above me and to the right, but it's locked.

There's also a lift car 50ft above me, and it suddenly looks awfully ominous. What if it starts to descend, resulting in Declan pancake?

Gary, the lift engineer who stopped the lift for us, has assured me that there is no way that can happen - but tell that to my sweating palms. He has also given me a tutorial on how to unlock a sealed elevator door from inside the shaft, so that's my next objective.

I haul myself up, balance on a ledge a couple of inches wide, and grasp at the lock at the top of the door. It opens. I'm out, and the producer is waiting for me.

"Great," he says. "Well done. Now… One more time."

Drilling into the vault

Everyone has been asking how on Earth residents and security guards didn't hear loud subterranean drilling.

How quickly can you drill through reinforced concrete?

But when you're operating a drill, it becomes clear why more people weren't disturbed. It's diamond-tipped and it doesn't vibrate like a drill you might have at home.

As it slices inexorably into the wall at the exertion of even a little pressure, it emits a steady whine that isn't anywhere near as loud as you expect. You can talk to the person beside you by just slightly raising your voice.

Another fact - drilling the holes that were needed didn't take as long as has previously been reported. I drilled a hole in a reinforced concrete wall which was exactly the same dimensions as that drilled by the thieves. It took me and our drilling expert just two hours and 20 minutes to make the hole we needed.

Recent media reports have greatly exaggerated that fact, and it has a direct bearing on the investigation. Far from drilling all night, and having to return on a separate night to continue the raid, my estimate is that the thieves could have been in the vault by about 02:30 BST on the first night of the heist.

Which brings us to one of the most perplexing aspects of this crime.

Alarm testing

Opening the boxes

I wanted to try getting into the security boxes themselves, now that we were "in" the vault. How much time would that take? Would it be arduous? To try to understand, I used a set of manual tools to open similar boxes.

As you might expect, I had never done it before, and I had no help or advice. The first one I opened took me five minutes. Not long afterwards, using a lump hammer and brute force, I opened a box in 40 seconds.

How hard is it to break into a safe-deposit box?

All of this is significant for the investigation that is now ongoing, because it gives a very different perspective on the timeline of the raid, and even the real motivation of the thieves.

In short, my experience suggests they had more than enough time to open far more boxes than they did. In fact, even if they had only been in the building for only one night, and only one man had gone into the vault, they could easily have opened more boxes.

But they came back for several hours on a second occasion. Quite simply there are missing hours, and to me that casts a whole new complexion on this crime.

The heist has been good news for a local locksmith

Declan Lawn presents Britain's Biggest Diamond Heist? The Inside Story on Sunday on BBC Two at 22.00 BST. You can catch up with the iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.