The women who are obsessed with Parkour

- Published

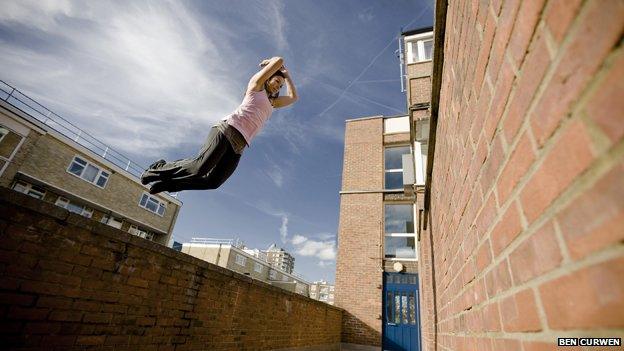

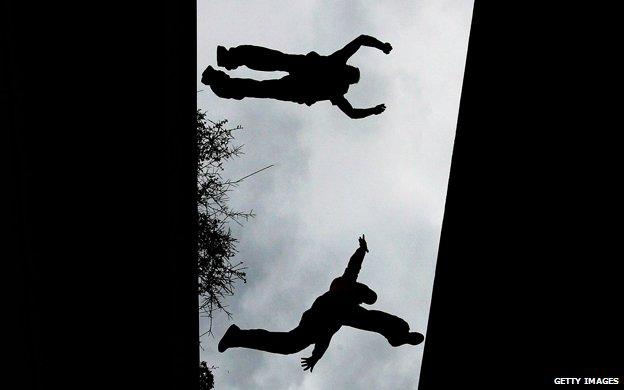

Parkour is a sport that revolves around moving quickly and creatively over obstacles. It has its roots in military training, but it has a growing following - especially among women. Author Christopher McDougall joined a crew as they made their way through the urban terrain of London.

On the Thursday morning I arrive in London, my phone pings with a message from a teenage mother and school dropout named Shirley Darlington: "Kilburn tube station, 7pm."

I get there 10 minutes early, but about 20 women are already warming up, including the British movie actress Christina Chong and her sister Lizzi, a professional dancer.

Every Thursday, Shirley emails the 100 or so members of her all-female Parkour crew, revealing the secret location for that night's challenge. She keeps the venue a surprise so her crew never knows what to expect, and she keeps guys away because the biggest threat to Parkour - as even Parkour's all-male founders would agree - is testosterone.

"Young guys turn up, and lots of times all they want is the flash and not the fundamentals," says Dan Edwardes, the master instructor who gave Shirley her start. "They want to backflip off a wall and leap around on rooftops. With a group of lads, you'll get the show-off, the questioner, the giddy one. But in a women's group, there's none of that. It's very quiet. They get to it."

What I was after was even more fundamental than the fundamentals. I'd only come to Parkour by accident while chasing the secrets of the most remarkable athletes of our time - World War Two resistance fighters.

I'd become fascinated with the underground when I realised it wasn't made up of hardened soldiers. Often, they were civilians hiding behind enemy lines who had to live off the land while attacking Hitler's forces in gruelling hit-and-run operations.

Take Crete - on that small Greek island, farmers and shopkeepers were joined by British academics and poets who'd essentially been recruited just because they knew Ancient Greek. For the next four years, these misfits routinely covered ultra-marathon distances over mountain peaks and pulled off feats of strength and endurance that would stagger an Olympic athlete. I wanted to learn - what was their secret? And could I master it too?

One clue came from Samuel Gridley Howe, an American medic who joined the Greek Revolution in the early 1800s. Howe was amazed by the way Greek fighters seemed to bounce along the landscape, using so little effort that they barely needed food or rest. "A Greek soldier," Howe commented, "will march, or rather skip, all day among the rocks, expecting no other food than a biscuit and a few olives, or a raw onion, and at night, lies down content upon the ground with a flat rock for a pillow."

More than 100 years later, a British operative on Crete during WW2 recalled how difficult it was to keep pace with a heavyset Cretan twice his age who "tripped daintily along from boulder to boulder, his body bouncing with every step like an inflated rubber beach toy".

The origins of Parkour

Takes its name from phrase "parcours du combattant", the military obstacle course training devised by French physical educationalist Georges Hebert (1875-1957)

Modern Parkour was popularised by French actor and stuntman David Belle - his video "Speed Air Man" played a large part in popularising the sport

Practitioners of Parkour are often known as traceurs

To me, this sounded remarkably similar to what I knew of Parkour, the French street art of using the body's natural elastic recoil to leap and flow across the urban outback.

I wondered if Parkour's pioneers, seven French street kids who called themselves the "Yamakasi", and learned their basic moves from a survivor of colonial jungle fights in French-occupied Asia - might have rediscovered the same ancient athletic principle which allowed the Cretans to cover fantastic distances with remarkably little effort.

Once you learn Parkour's basic moves, I'd been told, the world around you changes. You don't see things anymore - you see movement. Maybe if I got some Parkour under my belt, the tumbled boulders on a Mediterranean island would transform from stuff in the way, into stuff to bounce off. "The same thing we do in the city, they do in mountain terrain," Dan Edwardes says. "That 'Cretan bounce' you were asking about? That comes from precision. When you hit a rock and bounce off, it's because you hit it square. You can't brake or doubt. You have to trust your body and go."

And when he says "your body", he means it. Movement isn't natural if it only applies to half the species, he says, which is why he's convinced that Parkour is one of the truest representations of human athleticism.

Most spectator sports were created by and for men, so they accentuate specific male attributes of bulk, upper-body strength, and explosive power. But Parkour is grounded in the full range of natural human movement, he says, so it's the ideal sport for everyone, regardless of age, gender, or athletic background.

That's what makes Shirley Darlington both an ideal coach and case study. She was 16 when she dropped out of school to help support her family after her father died, and 19 when she had a baby of her own. She sold shoes by day while getting her education at night, then began university studies while creating a job for herself with the health council as a mentor for other teenage mothers.

"I had to grow up fast," she explains. "I was working full-time and caring for an infant. I didn't have time to play." She only went to her first Parkour class to support a cousin who was too shy to go on her own.

They found themselves alone in a sea of lads pulling themselves over brick walls twice as high as their heads. But the heckling and the babying they expected never came.

When Shirley and her cousin struggled with a drill, two of the lads who'd already finished silently circled back and completed it by their side. "There's no written code for Parkour, but pretty much everywhere you find the same principles," Dan says. "At some point, even the strongest person freezes on a jump. It teaches you humility and reminds you where you came from."

That's why no one ever finishes a challenge alone. "Even from the beginning, with the Yamakasi," he points out, "Parkour was always about community."

Night after night, he watched Shirley show up for class even though she was weak and clumsy and usually exhausted from work and class and pre-dawn baby feedings.

For two years, Shirley struggled to do her first pull-up. "She used to just hang from the bar," Dan says. "She'd pull and pull and she wouldn't move one centimetre."

But she continued showing up and grabbing for the bar until a year later, Shirley nailed her first "muscle-up" - a challenging and essential Parkour manoeuvre in which you continue the pull-up until you're waist high on the bar and can vault yourself on top.

By her fifth year, Shirley was not only outperforming the men, she'd become the one circling back to help struggling lads. The real obstacle wasn't strength, she discovered. It was trust. "I never knew what my body could do, so it took a long time to build the confidence to throw my full weight into a movement," Shirley says. "Once I did, it changed everything."

On this Thursday evening, Shirley leads me and 40 or so women off at a jog, arriving about half a mile later at a cement courtyard in the middle of a high-rise housing estate.

Shirley has us line up at the top of a long, zigzagging access ramp and drop to all fours. We monkey-walk on hands and feet about 40 yards to the bottom, then bunny-hop up the stairs and do it again backwards, then crab style, then squat-hopping, each time with a new twist and a push-up between circuits.

By the 13th loop, my hands are cement-scuffed and my head is spinning from being at knee-height for so long, but the parade of hopping, bear-crawling, push-upping women shows no sign of slowing.

I look around for Shirley, but she's disappeared into our midst. "The best Parkour coaches are invisible," Dan tells me. "They get you started, then get out of the way."

I spot her again when three men take a seat on the wall and begin sharing a smoke and loud comments on the women's bodies. Shirley quietly peels off from the circuit and trots over to a swing set. She leaps for the crossbar, and in a blur somehow ends up squatting on top. She lowers herself from the bar with such slow grace and power that the three mopes on the wall shove their cigarettes in their mouths so their hands are free to applaud.

When Shirley's tribe heads out, I have to sling my bag on my back in a hurry and sprint to catch up. For the next two hours, north west London is our playground. Shirley leads us to metal benches, where we practice diving into shoulder rolls and popping back up on a dead run.

She finds a beauty of a wall where we work on running arm jumps - running straight up the bricks, basically, and grabbing for the top of the wall, and hoisting ourselves up when momentum dies and gravity takes over.

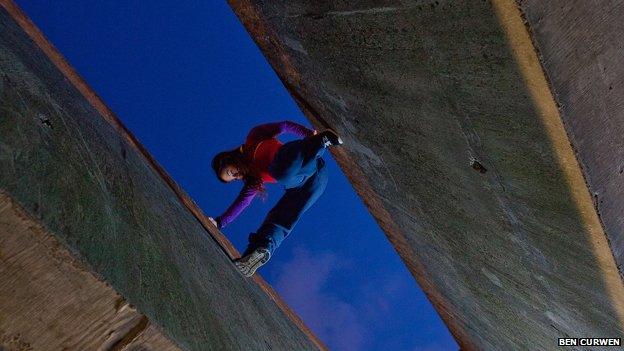

Well after dark, we're all clinging to a railing as we traverse a cement wall in a hanging squat. My feet are slipping and I'm in danger of dropping off when Lizzi Chong tucks in beside me.

"Get your knees higher," she says. "You're relying on your arms, but this is about legs."

Step by step, we work our way to the end, then drop to all fours and bear-crawl on hands and feet back to the beginning, press out our 40th or so push-up of the night, and get ready for another loop.

I try to thank Lizzi for the help, but she waves me off. "I needed a hand to hold when I started because I thought it was too dangerous," she says. "If I break an ankle, that's my career." But after her first class, she was hooked.

"I could see the dance in it. The flow, the rhythms, the strength and danger. You're always on the edge of fear, because your body senses it can do more than your mind will let it."

By the time Shirley cuts us loose for the night, I never want to do Parkour again but can't wait to come back. I didn't just run and climb all over London - I still had its cement grit deep under my fingernails.

This must be what one of the Cretan resistance fighters meant when he said a true citizen is a dromeus - a runner. Someone who can handle any obstacle and circle his hometown like a guardian spirit.

"We have to shape our training to fit our lifestyle," Dan Edwardes says. "We're no longer surrounded by trees, so we have to learn to climb walls."

Christopher McDougall is the author of Natural Born Heroes: How a Daring Band of Misfits Mastered the Lost Secrets of Strength and Endurance

More from The Magazine

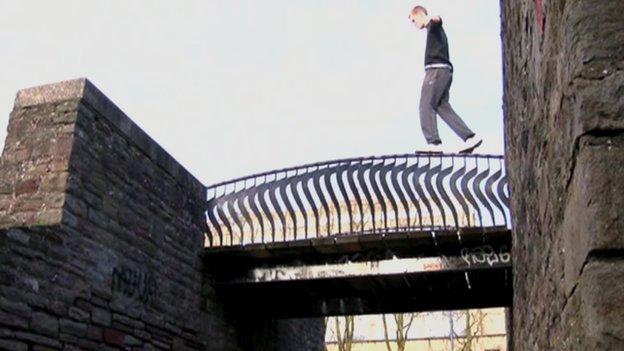

James Rudge was born with one arm and is earning a reputation online for doing parkour around Bristol, the city he loves.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.