Tracing the children of the Holocaust

- Published

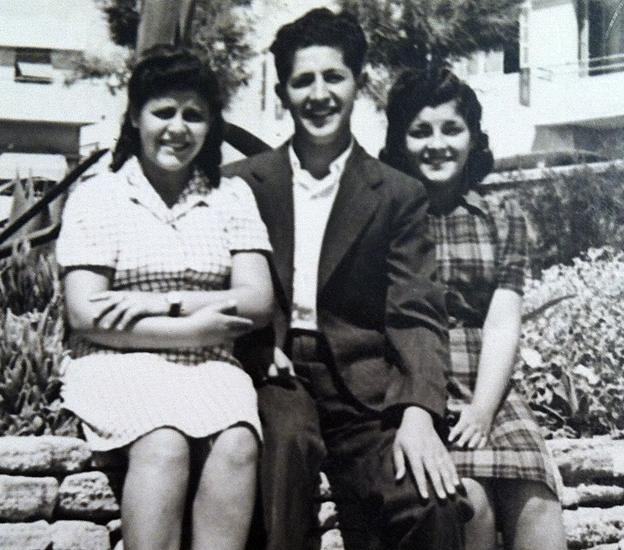

Hana Katz in Israel after the war

After World War Two, the BBC attempted to find relatives of children who had survived the Holocaust - they had lost their parents but it was believed they might have family in Britain. Seventy years on Alex Last has traced some of those children and found out what happened to them.

It all began with a rare recording of an old radio broadcast, which starts with the words: "Captive Children, an appeal from Germany."

One by one, for five minutes, the presenter asks relatives of 12 children to come forward. With each name comes a short but devastating summary of the child's ordeal under the Nazis.

Listen to an excerpt from the broadcast

"Jacob Bresler, a 16-year-old Polish boy, has survived five concentration camps, but has lost his entire family…

"Sala Landowicz, a 16-year-old Polish girl, who's in good health after surviving three concentration camps…

"Gunter Wolff, a German Jewish boy, now stateless. The boy is 16 years old and has experienced the ghetto at Lodz, and the Buchenwald concentration camp...

"Fela and Hana Katz, their father and mother have died, they have lost track of two brothers and three sisters."

And so it went on.

This broadcast went out on the BBC Home Service after the news, at 6:10pm, on 5 August 1946. It is the only one of the series of five episodes that has survived in the BBC archives.

When I heard this recording, I instinctively wanted to know what happened to these 12 children. Did they find who they were looking for? Did they find anyone? So 70 years on, I began to search for them, and in the end I met four of the children.

In May 1945, a year before the broadcast was made, Jacob Bresler was dying. He was on a train near Munich in Germany, locked in a cattle wagon full of fellow concentration camp inmates, many of whom were already dead. The SS were moving the prisoners away from the advancing Allied armies.

"We had been dragged around for two weeks without food or water. I weighed about 60 pounds (27kg). When I was liberated by the Americans we crawled on our bellies, because we could not walk, and kissed the tracks of the tanks," he says.

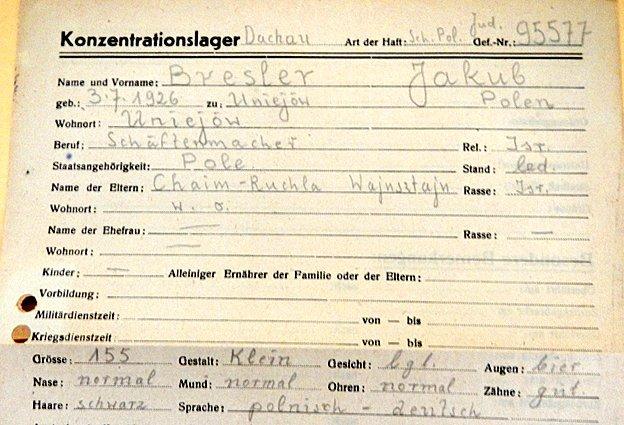

Bresler's card from Dachau concentration camp

Around the same time, hundreds of miles to the north, in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, 12-year-old Fela Katz and her 14-year-old sister Hana were desperately trying to keep their mother alive.

They were all that remained of a family of 10, from Lodz in Poland. Their father was dead, their brothers and sisters had disappeared after being taken away by the SS. But Fela and Hana had managed to stay with their mother through the horror of the camps - they had stopped calling her mum, in case someone overheard, and separated them.

Now their mother was sick with typhus and she was dying, weeks after Belsen's liberation by the British army.

"My sister all the time tried her best, [saying] 'Keep strong, you will see it's going to be OK,'" says Fela.

"They didn't cure her properly, she didn't get care. No-one got special care. It was very hard to deal with it." Their mother died in Belsen on 15 May, one week after VE day.

Fela Katz today

Meanwhile, Sala Landowicz and her two younger sisters, Regina and Ruth, also from Lodz, were alone in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. A year earlier, they had lost their mother and a younger sister in Auschwitz, when their mother had refused to be separated from her youngest child and went with her to the gas chambers.

Now, in Theresienstadt, they were barely alive. Then they head the rumble of soviet tanks at the gates of the camp.

"I went out and I saw a Russian tank, and I jumped on the step of the tank and the solider gave me bread. Then everyone came out, and everyone wanted the bread, and I fell down and everyone was stepping on me," says Sala.

Unknown to Sala, a 16-year-old German Jewish boy, Gunter Wolff, was also in Theresienstadt that day, watching the Soviets arrive.

"I remember when I first saw the Russians. They were all singing and they were throwing food at us. They had never seen such starving people," he says.

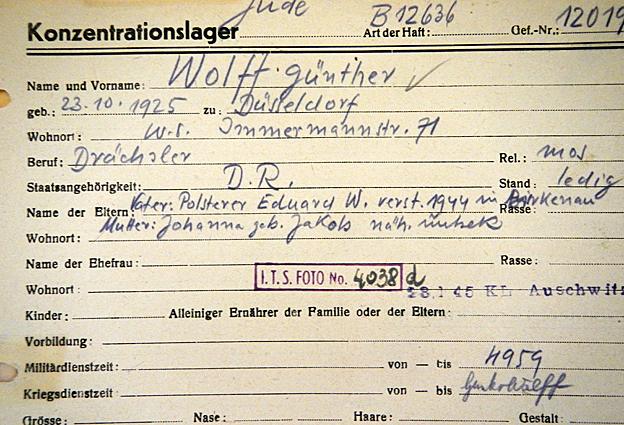

Gunter Wolff's registration card showing his arrival at Buchenwald - he had previously been in Auschwitz

Gunter was alone too. He'd lost both his parents in Auschwitz. He'd survived several concentration camps, and death marches through the snow, before ending up in Theresienstadt. While other prisoners collapsed and were shot by the SS, he kept going by reciting a poem he'd learned in school back in Germany before the war: "No matter how much winter, throwing storms of snow and ice, spring will be coming." It had become his mantra. After watching the Soviet troops liberate the camp, he finally collapsed.

Gunter, Sala, Fela and Jacob were without parents, without homes, and they were all near death.

Most were moved to one of the hundreds of Displaced Persons (DP) Camps which sprang up across Europe. Some were created in former concentration camps, others were parts of towns, which had been requisitioned by the Allies.

A displaced persons camp in Germany, March 1945

Sala and her sisters were taken from Czechoslovakia to the Landsberg DP camp in Bavaria. Jacob Bresler, who had been freed from the cattle wagon by the Americans, ended up there too. It was a town within a town, and became one of the largest DP camps for Jewish survivors.

"We were like zombies," says Jacob. "We were fed, we were free, sort of, but we couldn't comprehend, because we were too damn young. What could a boy of 16 know of life, even though we had lived three lifetimes?"

As the children recovered, their first thought was to start looking for their missing families.

"In Landsberg there was a bulletin board, where every day there were postings of people looking for people. I did not find anybody," says Jacob.

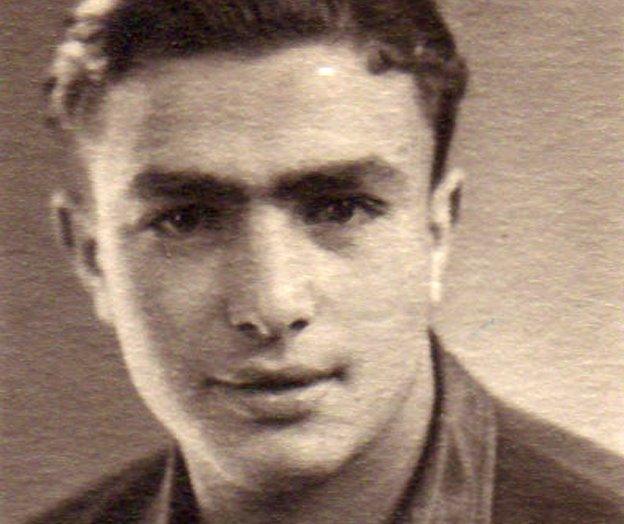

Jacob Bresler, aged 18, in the Landsberg DP camp

Jacob came from a family of eight, which had lived in the small town of Uniejow in Poland. He'd been separated from his parents and sisters earlier in the war, but had stayed with his brother Josef through the Lodz ghetto, and the Auschwitz and Kaufering concentration camps. Then in late 1944 they were separated too. Jacob saw his brother one last time as their work parties crossed paths.

"I urged him to keep going, and he said to me, 'I'm not going to survive… I don't want to live this way.' And he didn't. I was different, I had to survive. I have done everything, I stole, I did everything to survive." By the end of the war, Jacob was the only one of his family who remained alive.

Jacob Bresler's brother, Joseph, in 1936

Gunter Wolff began searching too. He had recovered from typhoid fever and decided to set off for the village in Germany where his mother had been born - the agreed rendezvous point if any of the family survived. He got there and waited for two months, but no-one else showed up.

While there, he met a British soldier who was eating a slice of white bread - whiter than any bread Gunter had ever seen. He stopped and stared. The British soldier offered him a slice and they got talking.

"He said, 'Oh my God, where are you going to go?' I said, 'I don't know. I came here looking for my parents.' He took one look at me and realised, we've got to do something."

The soldier introduced him to a dynamic woman from the UN, Regine Orfinger-Karlin. And Gunter became her project. She managed to get him on a children's transport leaving Belsen for the UK.

It was at about this time, that the children turned to the names and addresses of relatives overseas. These details had been drilled into them by their desperate parents before the families were torn apart, and later collected by aid organisations in the camps.

This is where the BBC broadcasts came in... and yet for some children, the relatives did not turn out to be the lifeline you might have expected.

When Gunter had arrived in the UK from Belsen he had immediately been diagnosed with tuberculosis and placed in a sanatorium. But he remembers meeting a cousin of his father's on the platform of Waterloo station.

"He looked more English than the English, with a bowler hat and umbrella. I said 'Uncle Theo!' and he said, 'We don't speak German here, we only speak English!' And still at Waterloo station he said to me, 'I just want you to know, your father and I never got along.' He lived in Golders Green. I went to his house, and the first thing I remember, he took out his keys and locked up every cabinet in the house while I was there." Gunter decided he would not stay.

"I learned very early the only reliable person is you, yourself," he says. "I still have that today."

For two years, Gunter stayed in the UK. A business friend of his father's arranged for him to receive a stipend, for which he felt enormously grateful. Only when it suddenly ran out was he told the money had actually belonged to his father in the first place - part of an arrangement he had made in case anyone survived. But while in the UK, Gunter had made contact with relatives in New York and through them he got papers to go to the US.

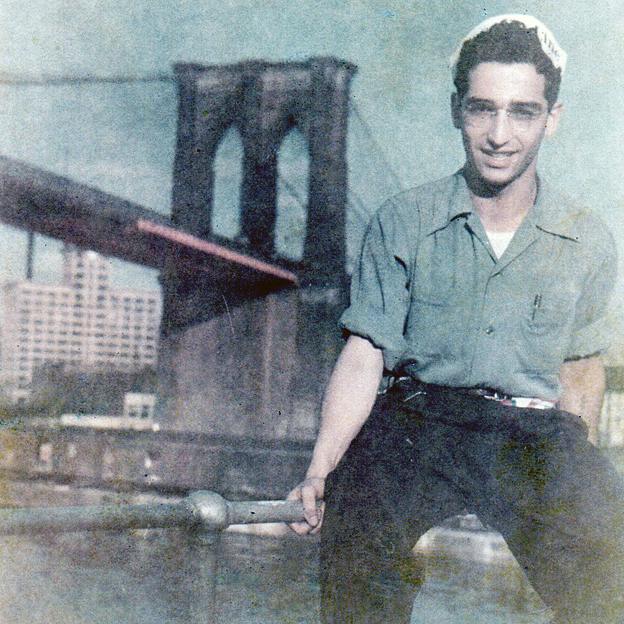

Gunter Wolff photographed against a backdrop of the Brooklyn Bridge

"You think that now we get to the Garden of Eden. No, no, no. I get to America. This woman picks me up, and I know they are well-to-do. And she says, 'Today is Thursday, we've got you a job starting Monday, and you can sleep in my husband's waiting room, he's a doctor and you can sleep on his couch.'

"So I go to work on Monday, I don't like it very much, but then it's pay day. And I get 11 dollars and 60 cents. And I get a pay cheque, and I say to her, 'Here's my pay cheque can you cash it for me?' and she says 'Sure'. And she gives me back 7 dollars and 60 cents. And I said, 'I think there's been an error, the cheque was 11 dollars.' But she says, "Yes but you have been sleeping on the couch!'"

Within a week he moved out.

Sala Landowicz and her sisters, Ruth and Regina, in the Landsberg DP camp got a response from the cousin they sought in London - a hospital doctor. But it was not what they expected.

"I got a letter back telling me I had to stand on my own two feet, and that kind of annoyed me, this attitude. So I wrote him, he needn't worry, I won't come to him for anything, that I will stand on my own two feet because I had a good teacher and that was Hitler. And he taught me a lot," says Ruth.

It's hard not to be shocked by such stories. We don't know the full circumstances, but for whatever reason no-one came forward to help most of the 12 children - and they alone had to decide what to do next.

Sala Landowicz met and married a fellow Holocaust survivor in the Landsberg DP camp. Her sister Ruth got married too, and through their spouses, they got sponsored to go to the US. Their sister Regina was devastated to be left behind, but ended up joining them a few months later.

Sala (Sally) with her sisters Regina (centre) and Ruth (right) after their move to the US

After the death of their mother in Belsen, Fela Katz and her sister Hana had been moved to a Jewish children's centre at the Zeilsheim DP camp near Frankfurt. While there, Fela decided she wanted to go to Palestine, while her sister Hana wanted to go to the UK.

"I said Hana, you are coming with me - I was not fair to her about it," says Fela.

In 1946, they were among a group of thousands of Jewish children who were given permission by the British government to go to Palestine. They were sent to a kibbutz and there Fela was given a new Hebrew name, Zippora. Then one day, someone came looking for them.

"We had exercises outside, and suddenly I saw from a distance two boys, and they came closer and closer and, suddenly I saw one of the boys was my brother, Israel. We fell one on the other, and this was the greatest thing that happened after the war.

"He'd had a very hard time. He was looking for us everywhere because he heard that we had survived, me, my sister and my mother. He was overjoyed but straight away he said, 'Where is mummy?' And our faces fell. We said, 'Mummy survived the war, but she passed away.' We went to a place to sit down and talk. It wasn't easy but we thought now we are almost a family. Three people, it is a family. But how long did it last? Nothing. He was called to go to the army, and he was killed."

Their brother, who'd survived the Holocaust, was killed in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Hana Katz (left) with her brother, Israel, soon after they were reunited

Jacob Bresler spent two years in the Landsberg DP camp in Germany, until one day in 1947, on the notice board, he found a message for him from a "Mr and Mrs Samuels from New York". He had no idea who they were. It turned out they'd been friends of his parents, and had seen his name in a list of survivors in a Jewish newspaper. They invited him to come to the US.

"I arrived in New York on the 25 December 1947. I will never forget the day as long as I live. It was very, very euphoric for me but also very tragic. Not knowing what awaits me, not knowing the language, not knowing the people I was going to meet. What am I going to do? I stood on the railing all night long. It was not a very happy time, It should have been euphoric but it wasn't, because I was alone."

The Samuels family turned out to be Jacob's saviours, however.

"Mr and Mrs Samuels were more than lovely. And they became my parents, practically, for the rest of their lives. They were angels. You don't meet people like this today, and if you do, you should carry them on your hands, and celebrate them as the most fantastic human beings that were ever alive. To this day, I do not have the words to express my gratitude, and they really loved me, and I loved them."

Jacob (Jack) Bresler today

In the US, Jacob Bresler became Jack Bresler. He went on to serve in the US Army before moving to Vienna to study opera. He's worked as a TV producer, restaurateur and businessman. He's now 86 years old, and has been married to his wife, Edith, for 55 years. He has a daughter and grandchildren. He remains very close to the Samuels family.

Gunter Wolff became Gary Wolff. After arriving in the US he worked all day and went to college at night, until he suffered a relapse of tuberculosis. He spent two years in hospital and had a lung and seven ribs removed. He eventually got married, and started a successful property business. Now 86, he too lives in Los Angeles with his faithful dog Teddy, and is very close to his two grandchildren.

Gunter (Gary) Wolff with his dog, Teddy

On arriving in the US, Sala and her husband changed their names. She became Sally Marco. She still lives near her sisters, Ruth and Regina in Los Angeles. They all have children, and grandchildren.

Fela Katz, now Zippora, and her sister Hana got married and started families of their own. Hana died in 2008, and is buried in Israel close to the brother who found them after the war.

Sala (Sally) with her sisters Ruth (centre) and Regina (right), earlier this year

In the end I found traces of 11 out of the 12 children from the broadcast. Most are no longer alive. All had taken different names. Seven had emigrated to the United States, four had gone to Israel. All had families of their own.

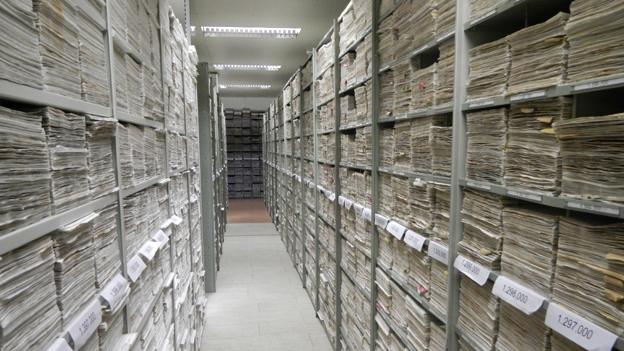

And was the BBC appeal for relatives successful at all? Well, documents from the BBC's own archives, reveal that there was a huge response from the public to the broadcasts. In total, contacts for 15 of the 45 children named across the series of episodes were found directly from the BBC appeals. In some cases the relatives were desperate to look after the children, though it's not clear how many of these offers were taken up.

My search took three months, and is now over. But many survivors of the Holocaust and their relatives have not stopped searching.

The International Tracing Service, set up by the Allies after the war to help reunite the millions of displaced, still gets 1,000 enquiries each month.

"I am still looking today," says Jack Bresler. "I even look at films from those days, maybe I will find somebody I will recognize, maybe someone from my family. But I doubt it, it's now 70 years since the war, and if they haven't given a sign of their lives - they are not alive."

The search

Finding these children was not easy. The first stop was the International Tracing Service, external in Germany. It holds files from the Nazi era, as well as post-war files. They had documents on almost all the children and even had some post-war correspondence. It was through them that I got a contact for Gunter Wolff. I found a contact for Jacob Bresler via an Austrian academic who had written a foreword for a memoir Jacob had written in the 1980s. But I also realised that some of the children would have gone to Israel. So I got in touch with the Central Zionist Archive in Jerusalem, external, which holds documents on Jewish emigration and runs courses in Jewish genealogy. They put their top man on the job, Gidi Poraz, who is an expert in tracing people. He organised an online community to help with the search, which grew from 20 volunteers to more than 600 in the space of three weeks - and they found details of six of the children, both in Israel and the US, including Fela Katz, and Sala Landowicz.

Gunter Wolff, Sala Landowicz, Jacob Bresler and Fela Katz tell their stories on The Documentary: Lost Children of the Holocaust. Click here to listen to the programme now, or tune in to the BBC World Service from 1805 GMT on Saturday 9 May.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.