Lawrence of Arabia and the crash helmet

- Published

When TE Lawrence - immortalised as Lawrence of Arabia - died 80 years ago he could not have known that the accident which took his life, and the surgeon who tried to save him, would eventually help to save thousands of others.

It was pouring with rain on the morning of Sunday 19 May 1935 when TE Lawrence died.

The man made famous by his Great War exploits in the Middle East finally succumbed to the head injuries he had suffered six days earlier in a motorcycle accident.

"In Lawrence we have lost one of the greatest beings of our time," said his friend Winston Churchill. "I had hoped to see him quit his retirement and take a commanding part in facing the dangers which now threaten the country."

It was not to be. At the age of 46, Lawrence of Arabia was dead.

Mourning was international. The New York Times called it a "tragic waste" and speculated that the accident which brought his death had been "unwarranted and perhaps avoidable".

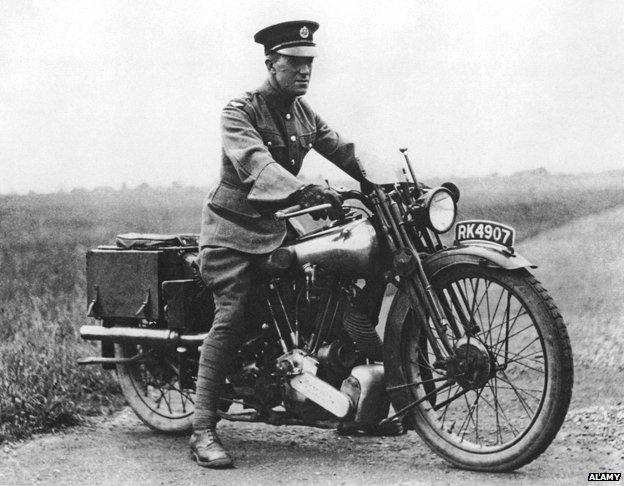

Lawrence had been pitched over his motorcycle, a Brough Superior SS100, near his Dorset home. A dip in the road apparently obscured his view of two boys on cycles ahead. The manoeuvring to avoid them cost him his own life.

The machine on which Lawrence suffered his fatal crash was guaranteed to be capable of more than 100mph, though there is no firm evidence that he was speeding recklessly when he came off it.

Lawrence had nicknamed it "Boa" or "Boanerges" which means "Son of Thunder" in Aramaic, and recorded his love of speed on previous rides.

"Boa and I took the Newark road for the last hour of daylight. He ambles at forty-five and when roaring his utmost, surpasses the hundred. A skittish motor-bike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth," he wrote.

Lawrence of Arabia 1888-1935

British scholar, writer and soldier who mobilised the Arab Revolt in WW1

A trained archaeologist with deep sympathies for the Arab people, Lawrence became an adviser to the Arabs and led small but effective irregular force against Turkey, attacking communication and supply routes

Sensationalised accounts of Lawrence's war exploits made him famous, but he spent the rest of his life trying to escape his own celebrity

His memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, formed the basis of David Lean's 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia, starring Peter O'Toole (pictured)

Whether Lawrence was riding safely in the run-up to the accident is unclear. "It's difficult to know exactly what the road would have been like in 1935 because it has changed so much, but the evidence is it was purely an accident," says Philip Neale, chairman of the TE Lawrence Society.

"He lost control and went over the handlebars. The Broughs didn't have fantastic brakes. The roads were very different in those days. Even the road in Dorset would have allowed some speed because traffic was light."

There was no mention in his obituaries that Lawrence had been without a crash helmet. In 1935 riders were typically bare-headed. Lawrence's death was to help change that - eventually.

One of the medics who attended Lawrence was a young doctor called Hugh Cairns, one of Britain's very first neurosurgeons.

His post-mortem examination established that Lawrence had suffered "severe lacerations and damage to the brain" when his unprotected head struck the ground. Had he survived, brain damage would probably have left him blind and unable to speak.

The loss of Lawrence was not forgotten by Cairns.

"We know from Cairns' diaries that he was thinking very hard about head injuries to motorcyclists and crash helmets before World War Two. They were mentioned in his diaries and the first mention is around the time of TE Lawrence's death," explains Alex Green, consultant neurosurgeon at the Nuffield Department of Surgery in Oxford, which Cairns founded.

Cairns began to gather evidence on head injuries suffered by bikers. It was pioneering work.

It was more than six years after Lawrence's death though before Cairns was ready with his first research. In October 1941, and by now consulting neurosurgeon to the Army, he published his initial results in the British Medical Journal. The article was entitled "Head Injuries in Motor-cyclists - the importance of the crash helmet".

It revealed that in the 21 months before the start of WW2, 1,884 bikers had been killed on British roads. Of the cases Cairns studied, two-thirds suffered head injuries.

Things got even worse with the start of the blackouts prompted by air raids, despite petrol rationing reducing traffic. In the 21-month period from September 1939, 2,279 bikers died, or roughly 110 a month - an increase of 21%.

1959: A motorcycle helmet is tested

The contrast with modern figures is a stark one. In 2013, 331 bikers - roughly 28 a month - died on British roads, despite the huge rise in traffic volume.

Cairns was careful not to claim that crash helmets would solve everything. He was certain though that they would help.

"There can be little doubt that many patients in this series would have lived if their heads had been adequately protected," he wrote.

His biggest problem, he conceded, was finding enough riders who did wear helmets voluntarily to show it made a difference. Cairns could only gather evidence from seven riders wearing helmets who were involved in accidents. All survived.

"In all of them the head injury was mild, though in four there had been considerable damage to the crash helmet," he wrote.

The Army, at that point losing two motorcycle riders a week in accidents, was convinced. In November 1941 it ordered all despatch riders to wear helmets. Cairns had won his first victory.

What the Highway Code says

"On all journeys, the rider and pillion passenger on a motorcycle, scooter or moped MUST wear a protective helmet. This does not apply to a follower of the Sikh religion while wearing a turban. Helmets MUST comply with the Regulations and they MUST be fastened securely. Riders and passengers of motor tricycles and quadricycles, also called quadbikes, should also wear a protective helmet. Before each journey check that your helmet visor is clean and in good condition."

"He provided proper scientific data of the beneficial effects of crash helmets and that was the thing I think. Although people had thought about it as a good idea before they didn't have the data," says Green.

Cairns was far from finished on the subject. Now he could start to compare despatch riders, in helmets, with civilian riders, still generally bare-headed.

By 1943 Cairns was able to show, in another BMJ paper, that a good helmet could reduce skull fractures in bikers who suffered head injuries by 75%.

Three years later, Cairns was appeal to go further. His 1946 study in the BMJ showed that total motorcycle deaths had fallen from a monthly peak of nearly 200 just before the Army introduced helmets to around 50 towards the end of the war - even with civilians still not wearing them.

Cairns was now sure of his evidence.

"From these experiments there can be little doubt that adoption of a crash helmet as standard wear by all civilian motorcyclists would result in considerable saving of life," he concluded.

Bikers in helmets, 1960

Despite Cairns's painstaking research and analysis though it was not until 1973 that the House of Commons voted to make wearing a crash helmet on a motorbike or moped mandatory.

Cairns's evidence was not in doubt, and riders increasingly adopted helmets out of choice in the post-war years. For defenders of individual freedom however, that right to choose was sacred.

One opponent of the plans for compulsion was Enoch Powell, who attacked the proposals in the House of Commons in April 1973, in the debate on the bill which made helmets compulsory.

"The maintenance of the principles of individual freedom and responsibility is more important than the avoidance of the loss of lives through the personal decision of individuals," Powell told fellow MPs,

"Whether those lives are lost swimming or mountaineering or boating, or riding horseback, or on a motor cycle."

Enoch Powell MP opposed compulsory helmets on libertarian grounds

The compulsory wearing of crash helmets marked a turning-point in road safety. Libertarians like Powell had lost the argument, and more compulsion followed, albeit after further opposition.

In 1983, after several Parliamentary setbacks, seatbelt wearing in the front of cars became compulsory. By 1991 all car passengers were required to wear one.

Whatever the arguments about freedom of choice, there's no doubt that modern crash helmets save lives.

"In our unit it's rare to see motorcyclists with head injuries. We deal with a population of three million and we see maybe one a week. You would expect the numbers to be much higher, given there are many motorcycle accidents. I've no doubt helmets must prevent or reduce many of those injuries," says Green.

Hugh Cairns did not live to see the change to the law his research helped to bring about. He died of cancer in 1952.

It's seems likely Cairns would have been pleased. But how a free spirit like TE Lawrence would have reacted to being forced to wear a motorcycle helmet is another matter.

Road safety in The Magazine

How did the UK get the 30mph speed limit? (March 2015)

How safe is cycling? (November 2014)

Do speed cameras cut accidents? (July 2010)

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.