The difference between 'affirmation' and 'oath'

- Published

That most time-consuming of the traditional rituals surrounding the UK Parliament, the swearing in of all the MPs, has become an emblem of the changing shape of British society. A ceremony originally designed for exclusion - to keep out religious and political undesirables - has become a display of diversity, writes Stephen Tomkins.

Where 200 years ago all MPs would swear allegiance to the Crown in English, on the Authorised Version of the Bible, today they swear and affirm, in English, Welsh, Gaelic and Cornish, on (or ignoring) an array of scriptures, including the Koran, the Guru Granth Sahib, the Hebrew Bible, and the Christian scriptures in various languages and in Protestant and Catholic editions.

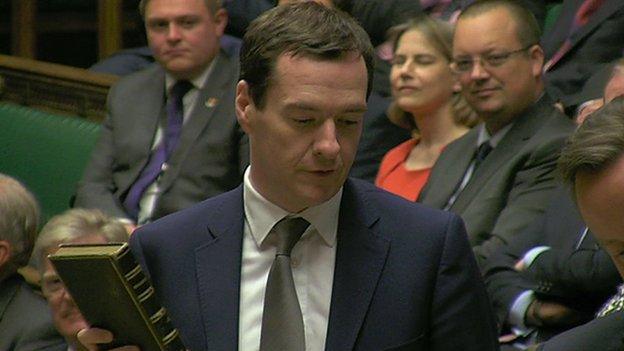

One MP on Tuesday - Kwasi Kwarteng - asked for the Book of Mormon, and the clerk seemed willing to go and have a root around for one, until it turned out he was joking. But there is an actual Mormon MP - Craig Whittaker. He made the same request, this time in seriousness, as Kwarteng, but the clerk did not have the Book of Mormon handy and, rather than hold up his colleagues, Whittaker opted instead for the Bible. MPs are even offered the opportunity to swear on the New Testament alone, an option of which George Osborne availed himself.

It is often assumed that the opportunity to "affirm" rather than swear was created so that atheists didn't have to call upon a deity they didn't believe in.

On Tuesday, Twitter buzzed with the revelation that Labour's eight most senior shadow cabinet members were atheists, as they all chose to affirm their allegiance. In fact, Parliament first came up with affirmation as an alternative for especially serious Christians.

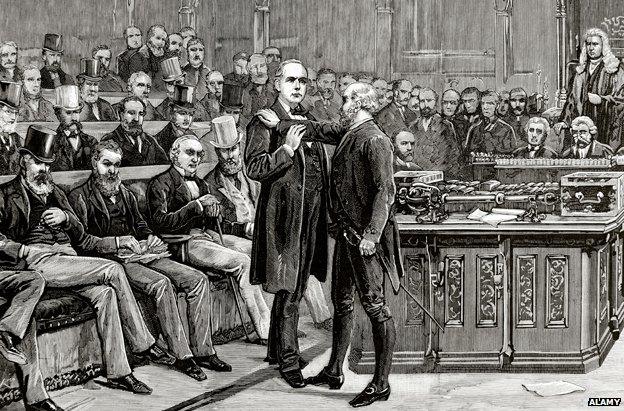

Charles Bradlaugh, an atheist, did not take the oath and was arrested for being in the House in 1880

A number of Christian groups from the 16th Century onwards refused to swear oaths on the Bible, the best known being the Quakers.

Quakers believed in living in such honesty that an oath could add nothing to what they said. As one of their founders George Fox said, when arrested and asked to swear the oath of allegiance: "Our allegiance [does] not lie in oaths but in truth and faithfulness."

When handed a Bible to swear on, Fox opened it at the verse that read, "Swear not, neither by heaven, neither by the earth, neither by any other oath" - a rather awkward text for the book that people are supposed to swear on.

It was in law courts that affirmation was introduced as an alternative to swearing. This was in 1695, many years before it reached Parliament, when it emerged that alleged criminals were going free because Quaker witnesses refused to give evidence against them.

Quakers, such as John Archdale in 1699, who were elected to Parliament could not take their seat, until the Quakers and Moravians Act of 1833 allowed them to take a version of the oath that did not mention God.

Catholics, meanwhile, had been deliberately debarred from Parliament by the oath, which involved recognising that the monarch rather than the Pope was in charge of the Church. A new oath was written in 1829 to allow Catholics to enter Parliament, but it was 400 words long, requiring them to "solemnly abjure any intention to subvert the present Church establishment".

Charles Bradlaugh, founder of the National Secular Society, was elected to the House of Commons in 1880

He was refused the oath because of his atheism. Asked to be allowed to affirm rather than take Oath of Allegiance

This was refused and he was denied his seat. A by-election was ordered and Bradlaugh was elected again

Refused to take oath and was ejected from Commons. Tried to re-enter and was arrested and imprisoned for a short time in the Tower of London

Offered to take oath but this was rejected. Finally took it in 1886

Jews were excluded by the oath less deliberately, as it included the words ''on the true faith of a Christian", as well as being sworn on the Christian Bible. The Jewish Liberal David Salomons was elected to Parliament in 1851 and took the oath, taking it upon himself to omit the problematic phrase. He was ejected from his seat a few days later, with a £500 fine for voting illegally in Parliament. Jewish MPs were allowed to swear without the phrase by Jews Relief Act 1858.

Affirming, as an alternative to swearing, was introduced by the Parliamentary Oaths Act of 1866, but did not at first apply to atheists or agnostics. The law applied to "the people called Quakers" and anyone else who was already allowed to affirm in a court of law, but atheists were not supposed to affirm in court because the affirmation was made "in the Presence of Almighty God".

The right to affirm in Parliament was finally extended to atheists in 1888, after Charles Bradlaugh, founder of the National Secular Society, was thrown out of the Commons four times for atheism, and re-elected each time.

He had first of all tried to make the affirmation which was intended for Quakers, and then later tried to take the standard oath (perhaps, like the republican Tony Banks in 1997, with his fingers crossed) but MPs who knew about his beliefs refused to let him.

Bradlaugh administered the oath to himself and was expelled anyway. Only on his fifth election to Parliament in 1886 was he allowed to swear and take his seat, and it was his Oaths Act which in 1888 extended the right to affirm to atheists and anyone else who objects to swearing.

The late Tony Banks crossed his fingers while he took the oath

Today, far from imposing the one true faith in its members, it seems hard to imagine a religious position that Parliament couldn't accommodate.

The remaining objections to the oath are political rather than religious.

Opponents argue that it overturns the will of the people by preventing democratically elected Sinn Fein members from taking their seats. Other republicans go along with the oath and voice their dissent, as in Tony Benn's version: "As a committed republican, under protest, I take the oath required of me by law."

Or Dennis Skinner's inimitable twist: "I solemnly swear that I will bear true and faithful allegiance to the Queen when she pays her income tax".

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox