The element that made the 20th Century shine

- Published

Chromium is the chemical element of modernity - the key to innumerable gleaming, spotless surfaces. Yet it also harbours a dark secret that featured in one Oscar-winning Hollywood film.

In the late 1920s, on either side of the Atlantic, two very different companies had the same idea - to play an architectural prank on the general public.

In London it was the Savoy Hotel & Theatre, while in New York it was the giant carmakers, the Chrysler Corporation.

The prank was to secretly clad their buildings in a shocking new material - stainless steel.

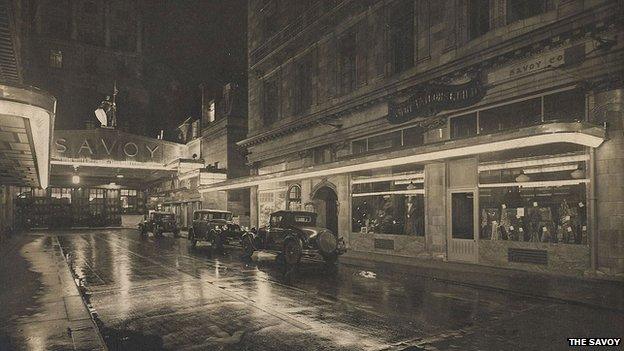

In 1929, the Savoy revealed the gleaming new signage over its entrance, with the hotel's name picked out in green fluorescent lights. It was the first ever decorative use of this metal on a building, and still stands there, spotlessly, today.

"They were theatre people, and they loved that dramatic sense," explains the hotel archivist Susan Scott.

"There's a fantastic quote by one of the directors: 'The Savoy is always up-to-date, and if possible, just a little ahead.'"

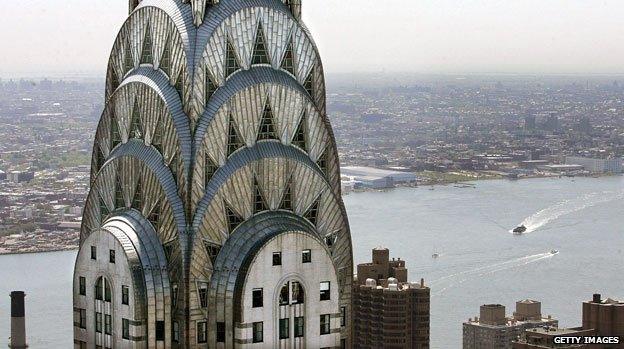

Still shiny...

And shortly after the sign was unveiled

And the director proved, in fact, to be just a little ahead of the competition. Across the Atlantic, the Chrysler Building was under construction in Manhattan.

Its now world-famous stainless steel apex was kept under wraps - literally and figuratively - until the last moment.

On 23 October 1929, the day before the Wall Street Crash, without warning the prefabricated 56m-tall spire was erected in just 90 minutes, pipping the aghast backers of a rival tower on Wall Street to the title of world's tallest building.

Then, on 29 January 1930, the wraps came off, revealing the shimmering steel covering the whole of the top of the building.

It is hard to comprehend the awe this would have aroused. Stainless steel, like plastic, is a material that we take for granted today, yet a century ago it was virtually unknown, and it was generally accepted that all steels must either be surrounded by some other protective material, or left to inevitable corrosion.

The advent of rust-free steel is down to a magic ingredient in its chemistry - chromium.

This metal, element number 24 of the periodic table, had been known since the late 1790s, when it was first identified by the French chemist, Louis Nicolas Vauquelin.

Louis Nicolas Vauquelin identified and named chromium

But its early uses were far removed from the silvery sheen of Art Deco architecture. Indeed, Vauquelin named this new metal after the Greek word for colour, chromos - because chromium is associated with an extraordinary array of colours.

The ore from which Vauquelin isolated his first shiny nuggets of pure metal was discovered in Siberia. Called crocoite, it resembled bright orange-red needles.

The mineral consisted of lead oxide and lead chromate, and the colour it produced became known to artists as "chrome red".

In fact it provided a range of colours. Increase the lead oxide, and the hue became a heavier red. Strip out the lead oxide altogether, and you were left with the brilliant yellow of pure lead chromate.

This "chrome yellow" would provide the iconic colour of the Swiss and German postal services, and US school buses. And also yellow lines on roads - as lead compounds are insoluble in water, they would not wash away in the rain.

A third pigment was provided by chromium oxide - "chrome green".

Chromium's journey from the artist's palette to the architect's drawing board is itself colourful and contentious, and takes us to Sheffield, the world's first steel town.

On the corner of Princess Street and Blackmore Street, in a rather bleak, de-industrialised district of the city, there is a plaque dedicated to Harry Brearley, the man who can best claim to have invented stainless steel, in 1913. Ironically, the plaque is slightly rusty.

"Metallurgy was in its infancy then," explains Derek Morton, a local steel history enthusiast. "This was where the Brown Firth Research Laboratories were. Brown Firth was one of the biggest Sheffield steelmakers, and Harry Brearley was the first manager of the laboratories."

Chromium: Key facts

Chemical symbol Cr

Element number 24

Discovered by Louis Nicholas Vauquelin in 1797

Named derived from the Greek for "colour" due to the many pigments it can produce

Traces of chromium provide the red colour to rubies, which are primarily made of aluminium oxide

Other chemists in the US, Germany, France and Britain had tinkered with chromium steels over the previous decades - the Germans even producing a stainless steel yacht for the Kaiser in 1908.

But Brearley was the first to realise their commercial significance. "Brearley was not only a genius in metallurgy terms," explains Derek. "He was also a very astute businessman."

Brearley was the first to see the material's commercial potential. In 1915 he applied for patents in the US and Canada for stainless steel cutlery, having broken with Brown Firth out of frustration that the firm would not file a UK patent on his behalf. The move would lead to disputes with Brown Firth, as well as with two American rivals, but it would eventually make Brearley a rich man.

Brearley's achievement was somewhat accidental. He was originally trying to develop a steel that would resist erosion, not corrosion, for use in gun barrels. And the first use of new his steel was also military - the exhaust pipes of biplanes for World War One.

But he then spotted a market that Brown Firth failed to exploit. He teamed up with the Sheffield cutler R F Mosley, and after the war the first stainless steel knives, forks and spoons began to be mass produced.

It was only in the mid-1920s that the classic stainless steel recipe was settled on - 18% chromium, plus the addition of 8% nickel, yielding a material that was far easier to cut.

From there, it was a short leap to the clean lines and polished surfaces of the Art Deco architecture of the interwar years.

Today, stainless steels are used not only for their good looks, but also to build structures that can withstand some pretty corrosive environments - from orange juice vats to subsea pipelines, and car exhausts to sewage containers.

"The steel is protected by a surface layer of chromium oxide, one of the hardest materials known," explains chemistry Prof Andrea Sella of University College London.

"And so that means the metal is completely encapsulated. That's why the steel resists further corrosion and retains its shine."

Chromium can just as easily be used to plate steel as to mix into it. Take a bit of steel, place it in a bath of acid containing dissolved chromium, and then pass an electric current through it, and the chromium will naturally stick to the surface of the metal as it discharges electricity.

This was how another great icon was born - the engine of the Harley Davidson motorcycle.

What Marlon Brando did for chromium

In the 1953 film, The Wild One, Marlon Brando rode a Triumph, rather than a Harley, but it too glistened with stainless steel. And Brando wore leather - lots of it - which also would not have been the same without chromium. The element plays an essential role in the tanning industry. When hides are soaked in a solution of chromium, this helps to cross-link their strands of collagen proteins into a mesh, making the leather more elastic and water-resistant.

Founded in Milwaukee in 1903, Harley's early bikes were plated in another impervious metal, nickel, giving them a dull sheen.

"They wanted something that could withstand the elements," explains John Warr, the third-generation owner of Europe's oldest Harley dealership, Warr's of Chelsea. "It's parked outside, used to American winters."

It was the move to the gorgeous polished surfaces produced by chrome-plating that brought the bikes to life. "Unlike an engine that might be hidden away in a car, it's all on show with a Harley," Warr boasts.

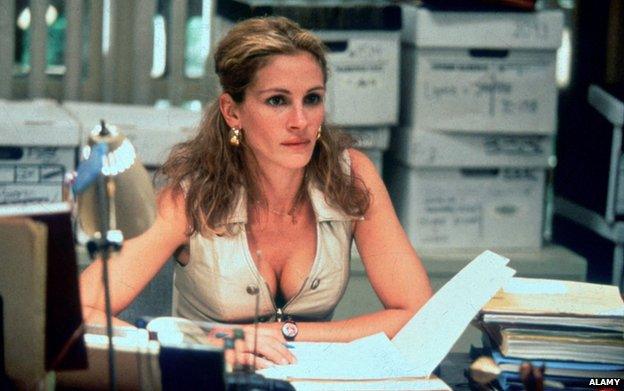

But chromium does have a dark side. It's the source of a danger that haunts tanners, electro-platers, paint manufacturers and welders - and was revealed in the Hollywood film, Erin Brockovich.

While metallic chromium is perfectly inert and safe, in certain chemical compounds chromium forms ions with a plus-six positive charge. If this "hexavalent" form of chromium then gets into the body - eaten, or dissolved in water, or vaporised by a welding torch and then inhaled - it can cause cancer.

Julia Roberts won an Oscar for her portrayal of Erin Brockovich

The real Erin Brockovich

"Hexavalent chromium is a really good anti-rust inhibitor," explains Brockovich - the real-life campaigner whose legal battle against the utility Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) in the California town of Hinkley formed the basis of the film.

"They had a very antiquated gas compressor facility, and the engines in there get really hot, and they run water through them, and you don't want that water to corrode, so they add hexavalent chromium."

This was back in the 50s and 60s. The wastewater leached into the surrounding water table. And, being in the Mojave Desert, Hinkley locals pumped this water up to supply their homes. Decades later the health consequences were becoming horribly evident.

"Every single person I talked to constantly had a strange rash, chronic nose bleeds, and respiratory [disease]," says Brockovich, who made it her mission to help the residents see justice.

With the case in arbitration, PG&E agreed in 1996 to pay $333m (£210m) in what was the largest settlement of a direct action lawsuit in US legal history.

"It was bitter-sweet," says Brockovich. "Because these people still died - many have died since the case. But they became an inspiration, because they stood up and fought."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.