How Penn Station saved New York's architectural history

- Published

The end of the first Penn Station pushed architectural preservationsts to act

In May, New York City's landmarks preservation agency blocked renovation changes to the Four Seasons restaurant in the modernist Seagram building. More than half-a-century ago, it was another architectural upheaval that led to the creation of a powerful city landmarks law.

To descend into Penn Station in midtown New York is to visit an architectural crime scene.

A cramped, subterranean space, interred under Madison Square Garden, it has the look and lifeless feel of an over-sized subway station.

Not even two storeys tall, the concourse has a low-hung roof, held up by stumpy, inelegant columns and dotted with air conditioning ducts, fluorescent lights and security cameras enclosed in smoke-glass half-domes.

Penn Station now lives below Madison Square Garden, a sport and entertainment complex

Battleship grey, which presumably had a futuristic sheen when the station was constructed in 1969, is the dominant colour. It gives an already bland building even more of a deadening air.

In what should be one of the world's great rail terminuses, the locomotives themselves are hidden further underground. To board them means descending deeper into this miserable warren.

Outside of the US penitentiary system, it is hard to think of a more joyless building.

What makes the "new" Penn Station all the more depressing is the black and white pictures on its walls of the old Penn Station, demolished in 1963.

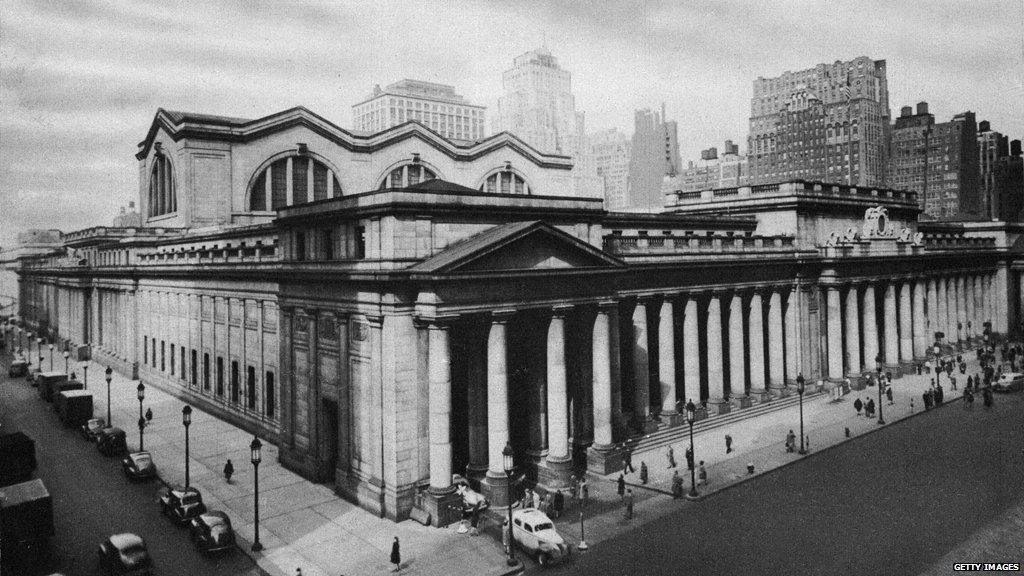

Penn Station, circa 1930

Wrecking balls were hurled at one of Manhattan's most noble buildings, a station which could boast a facade grander in scale that the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin and a concourse vaster than the nave of St Peter's in Rome.

Completed in 1910, and designed by the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White, it was inspired by the Baths of Caracalla from Roman antiquity, and shaped from the same stone as the Coliseum. Alas, a terminus designed to celebrate travel gave way to a transportation hub devised to process passengers.

Efficiency was the watchword. And remarkably, the building was destroyed with hardly any public outcry, save for the sorrowful cries of a small group of local architects.

The old Penn Station is torn down

In the ruins of the old Penn Station, however, are found the origins of the New York landmarks law.

Passed in 1965, the measure was intended to conserve the city's architectural heritage, a surprisingly radical idea in a decade with little respect for the past. This spring, the law has celebrated its golden jubilee.

Without the landmark law, some of New York's most-loved buildings would have disappeared from the urban landscape.

Mayor Robert Wagner signs the landmarks law in 1965

Much of SoHo's beautiful cast-iron district would have gone. Likewise, Tribeca and the Meatpacking district. In other words, the developers would have laid waste to what have recently become Manhattan's most desirable neighbourhoods.

Row upon row of Brooklyn's brownstones would also have been obliterated, so, too, Radio City Music Hall, the home of the famed Rockettes.

Still more felonious would have been the destruction of Grand Central Station, arguably the city's most breathtaking public space.

In 1968, Penn Central Railroad, the company that bulldozed Penn Station, announced plans for the redevelopment of Grand Central that could have led to the destruction of its facade and main waiting room.

The main concourse of Grand Central Station was saved from the same fate as Penn Station

Fortunately, the newly created New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, with the celebrity backing of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, stepped in. The railroad challenged the constitutionality of the landmark law in a test case that went all the way to the US Supreme Court in Washington, and the justices sided with the preservationists.

Fifty years on, the law protects 1,400 landmarks, 115 historic interiors, 109 historic districts and 10 scenic landmarks, including Central Park. Almost 30% of Manhattan's buildings are safeguarded.

They not only include heritage sites, like the RCA building lobby at the Rockefeller Center, but also modern architectural masterpieces, like Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum and the Lever Building on Park Avenue, one of New York's early curtain wall office towers.

The Stonewall Inn has moderate protection now because it is located in a historic district, but may earn greater protections through the Landmarks Preservation Commission,

The Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, the birthplace of the modern gay rights movement, will soon be considered by the commission for landmark status.

More recently, the city's landmarks preservation commission used the law to reject changes to the Four Seasons restaurant inside the modernist Seagram building in Manhattan.

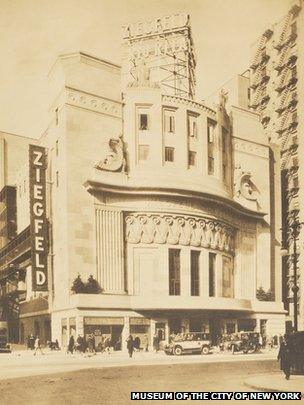

Not every noteworthy building was saved. The original Ziegfeld Theatre, one of Manhattan's great art deco temples, was demolished in 1966 to make way for a nondescript 50-storey skyscraper.

The Singer Building in Lower Manhattan, briefly the world's tallest structure at the start of the last century, was also hauled down.

A stunning skyscraper, designed in the Beaux-Arts style, it would have been a great adornment to the modern skyline.

Nowadays the main aesthetic threat to New York comes not from what is being torn down, but rather what is being built.

Its heritage buildings will remain just that, a legacy to the landmark law and the visionary preservationists who stood in the way of a mindless rush towards modernity.