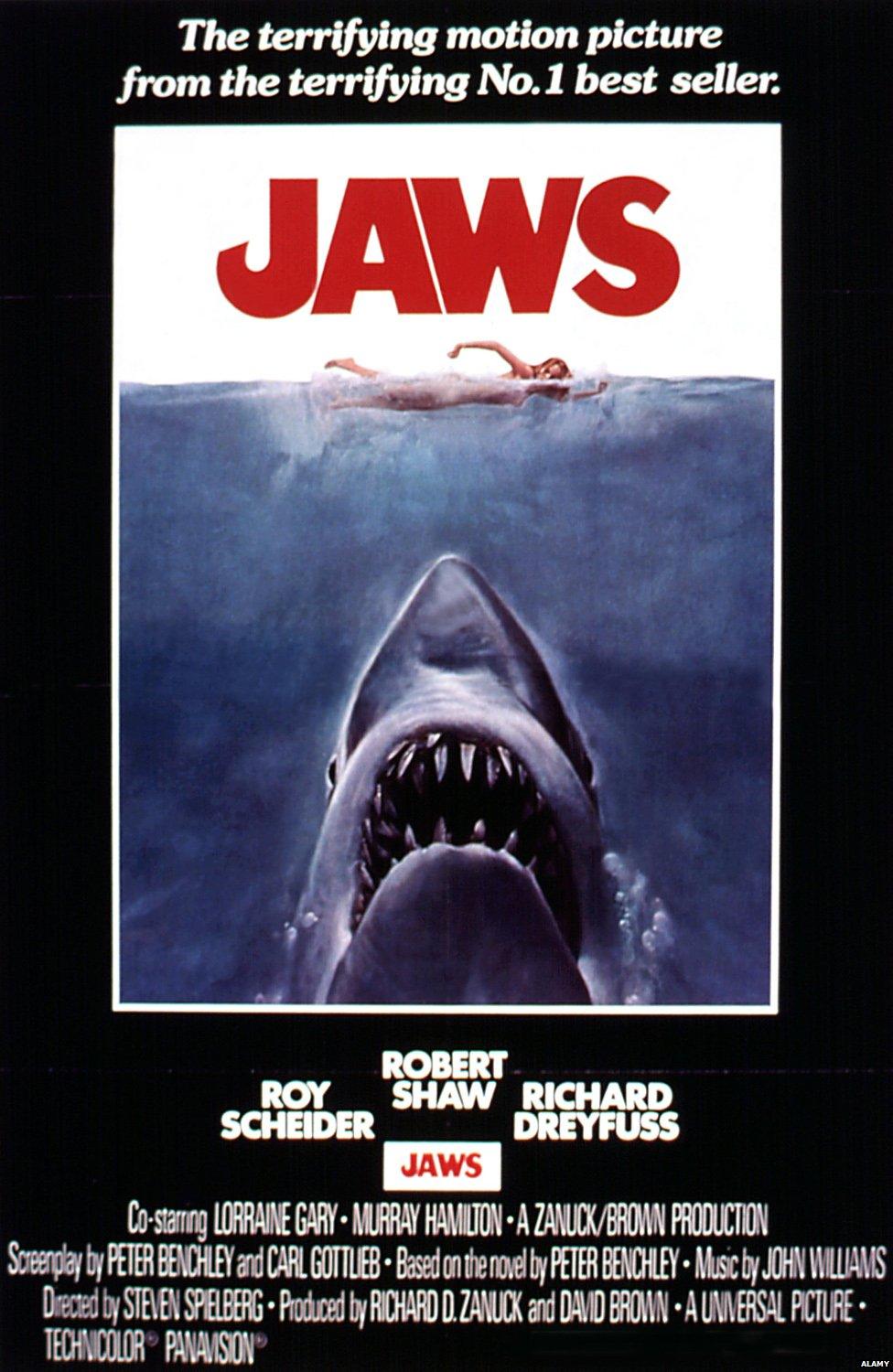

How Jaws misrepresented the great white

- Published

Billed as "The terrifying motion picture from the terrifying No 1 bestseller," Jaws has shaped the way many of us view sharks. But the creatures don't deserve their vicious reputation, writes Mary Colwell.

It was the summer of 1975 and even feeding the goldfish seemed fraught with danger. There was discernible tension at the seaside, and an earworm of two notes became a trigger for fear. Dum Dum, dum dum dum dum…

Forty years ago Jaws the movie hit the big screen. Cinemas everywhere held audiences in thrall at the thought of an oversized great white shark with bad attitude coming to a beach near you.

"Jaws was a turning point for great white sharks," says Oliver Crimmen, who's been the fish curator at the Natural History Museum in London for more than 40 years. "I actually saw a big change happen in the public and scientific perception of sharks when Peter Benchley's book Jaws was published and then subsequently made into a film."

The key problem Jaws created was to portray sharks as vengeful creatures. The story revolves around one shark that seems to hold a grudge against particular individuals and goes after them with intent to kill.

It's loosely based on a real incident in 1916 when a great white attacked swimmers along the coast of New Jersey.

"A collective testosterone rush certainly swept through the east coast of the US," says George Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research in Gainesville. "Thousands of fishers set out to catch trophy sharks after seeing Jaws," he says.

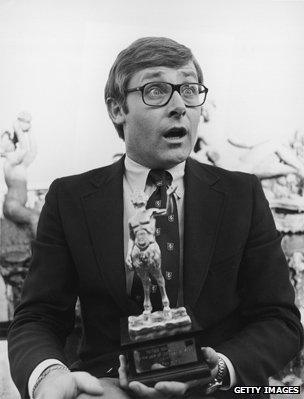

Peter Benchley collecting an award in 1975 marking the sale of a million copies of Jaws

"It was good blue collar fishing. You didn't have to have a fancy boat or gear - an average Joe could catch big fish, and there was no remorse, since there was this mindset that they were man-killers."

The author of Jaws, Peter Benchley, was deeply perturbed by this. "Knowing what I know now, I could never write that book today," he said, years later. "Sharks don't target human beings, and they certainly don't hold grudges." He spent much of the rest of his life campaigning for the protection of sharks.

Burgess suggests the number of large sharks fell by 50% along the eastern seaboard of North America in the years following the release of Jaws.

And research by biologist Dr Julia Baum suggests that between 1986 and 2000, in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, there was a population decline of 89% in hammerhead sharks, 79% in great white sharks and 65% in tiger sharks.

This change is not just down to sport fishing however, which is small beer compared to the numbers killed as by-catch from commercial fishing, and for use in shark fin soup which is popular in Asia.

But since the 1990s, protection for great whites has been established in many parts of the world including California, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. This has helped numbers recover somewhat, but there is a long way to go to return to pre-1975 levels.

Great white shark swimming through a school of fish

Find out more

What made Jaws such an effective thriller?

Natural Histories is a new series about our relationships with the natural world.

Listen to Sharks on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday 9 June at 11:00 BST or online after broadcast.

There is no denying though that Jaws touched something deep in our psyche. As the streamlined shape of the shark rocketed upwards to grab yet another victim, so our fear of sharks surfaced.

"Sharks in cinema before 1975 were a different category altogether," says John Mullarkey, professor of film and television at Kingston University. "After Jaws, this massive creature, 20ft to 30ft long can devour you whole… this was a strange discovery for the public imagination."

It is no surprise that we love to feel frightened by creatures like sharks and peer out between fingers over our eyes at movies like Jaws.

"We are not afraid of predators, we're transfixed by them," says renowned Harvard zoologist Edward Wilson. We are "prone to weave stories and fables and chatter endlessly about them, because fascination creates preparedness, and preparedness, survival - in a deeply tribal way, we love our monsters".

In reality, some large shark species certainly do attack humans - about 10 people a year are killed, usually by great white, bull and tiger sharks. Rarely though are the victims actually eaten - often they die from trauma.

There are two common reasons cited for attacks. Firstly, sharks mistake swimmers for their usual prey such as seals, especially if they thrash about in water and wear shiny objects that resemble fish skin. Secondly, sharks take an exploratory bite to see if we are suitable food and when they discover we are puny fare, we are spat out.

Some researchers take issue with this however - a shark's vision is too good and its sense of smell too sophisticated to confuse us with a seal, argue RA Martin, Neil Hammerschlag, and Ralph Collier from the ReefQuest Center for Shark Research. These are supreme ocean predators and are highly unlikely to make clumsy and possibly costly mistakes.

Sharks also have senses not available to most other animals. Pressure-sensitive pores scattered over their head and down the body mean they detect the slightest changes in pressure, enabling them to discern the smallest of movements even when other senses are restricted - such as their sight in murky water.

Sharks also possess sophisticated electroreceptors which help them hone in on the tiny electrical fields present around all living things, even creatures buried in sand.

Such highly-tuned animals are not likely to misidentify something as large as a human being. Far more likely, they conclude, is that sharks such as great whites see humans as fellow predators that could compete with them for food.

When they attack us they are not interested in eating us, they want us to leave the area. Martin, Hammerschlag and Collier have studied many shark attacks and say that prior to targeting a human, they show aggressive postures as a warning, and when that message is ignored they take action. The statistics appear supportive. The US averages 19 shark attacks each year but only one fatality every two years.

It is now 40 years since Jaws changed our perception of the ocean, and slowly but surely its grip is relaxing. There is an increase in concern for shark welfare and a greater understanding of the creatures as fascinating and impressive predators.

The calls for their protection are getting louder and although most people find it hard to love them, sharks are garnering more respect. We are less likely to criminalise them and more prone to accept their presence. It is a trend that would have delighted Peter Benchley.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.