Our deep need for monsters that lurk in the dark

- Published

Sea monsters are the stuff of legend - lurking not just in the depths of the oceans, but also the darker corners of our minds. What is it that draws us to these creatures, asks Mary Colwell.

"This inhuman place makes human monsters," wrote Stephen King in his novel The Shining. Many academics agree that monsters lurk in the deepest recesses, they prowl through our ancestral minds appearing in the half-light, under the bed - or at the bottom of the sea.

"They don't really exist, but they play a huge role in our mindscapes, in our dreams, stories, nightmares, myths and so on," says Matthias Classen, assistant professor of literature and media at Aarhus University in Denmark, who studies monsters in literature. "Monsters say something about human psychology, not the world."

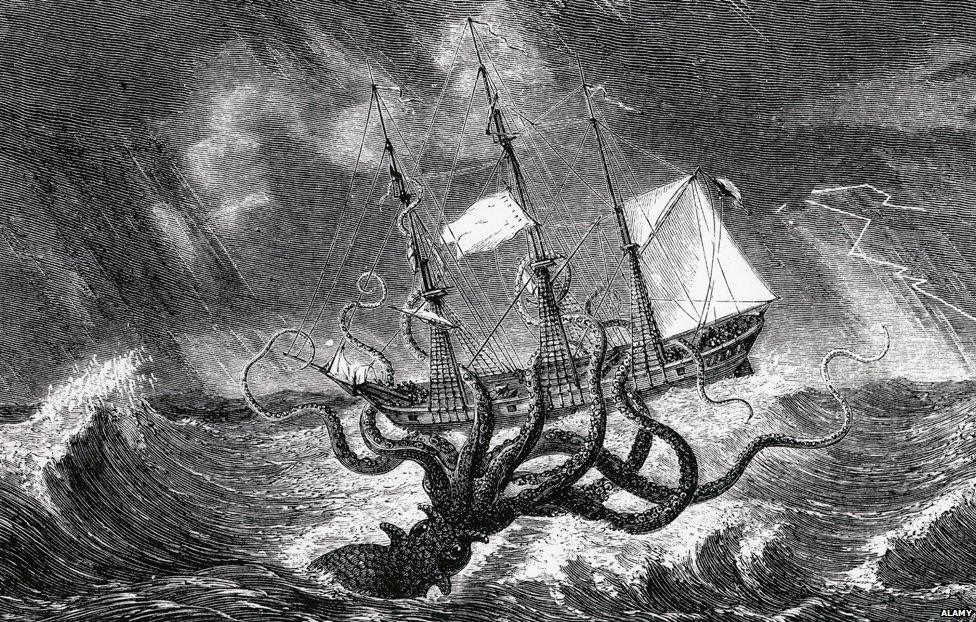

One Norse legend talks of the Kraken, a deep sea creature that was the curse of fishermen. If sailors found a place with many fish, most likely it was the monster that was driving them to the surface. If it saw the ship it would pluck the hapless sailors from the boat and drag them to a watery grave.

This terrifying legend occupied the mind and pen of the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson too. In his short 1830 poem The Kraken he wrote: "Below the thunders of the upper deep, / Far far beneath in the abysmal sea, / His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep / The Kraken sleepeth."

The deeper we travel into the ocean, the deeper we delve into our own psyche. And when we can go no further - there lurks the Kraken.

Most likely the Kraken is based on a real creature - the giant squid. The huge mollusc takes pride of place as the personification of the terrors of the deep sea. Sailors would have encountered it at the surface, dying, and probably thrashing about. It would have made a weird sight, "about the most alien thing you can imagine," says Edith Widder, CEO at the Ocean Research and Conservation Association.

"It has eight lashing arms and two slashing tentacles growing straight out of its head and it's got serrated suckers that can latch on to the slimiest of prey and it's got a parrot beak that can rip flesh. It's got an eye the size of your head, it's got a jet propulsion system and three hearts that pump blue blood."

Find out more

The tentacle of a giant squid, © The Trustees of NHM, London

Natural Histories is a new series about our relationships with the natural world

Listen to Giant Squid on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday 23 June at 11:00 BST or online after broadcast

The giant squid continued to dominate stories of sea monsters with the famous 1870 novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, by Jules Verne. Verne's submarine fantasy is a classic story of puny man against a gigantic squid.

The monster needed no embellishment - this creature was scary enough, and Verne incorporated as much fact as possible into the story, says Emily Alder from Edinburgh Napier University. "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and another contemporaneous book, Victor Hugo's Toilers of the Sea, both tried to represent the giant squid as they might have been actual zoological animals, much more taking the squid as a biological creature than a mythical creature." It was a given that the squid was vicious and would readily attack humans given the chance.

James Mason in the 1954 film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea © Everett Collection/REX

That myth wasn't busted until 2012, when Edith Widder and her colleagues were the first people to successfully film giant squid under water, external and see first-hand the true character of the monster of the deep. They realised previous attempts to film squid had failed because the bright lights and noisy thrusters on submersibles had frightened them away.

By quietening down the engines and using bioluminescence to attract it, they managed to see this most extraordinary animal in its natural habitat. It serenely glided into view, its body rippled with metallic colours of bronze and silver. Its huge, intelligent eye watched the submarine warily as it delicately picked at the bait with its beak. It was balletic and mesmeric. It could not have been further from the gnashing, human-destroying creature of myth and literature. In reality this is a gentle giant that is easily scared and pecks at its food.

Another giant squid lies peacefully in the Natural History Museum in London, in the Spirit Room, where it is preserved in a huge glass case. In 2004 it was caught in a fishing net off the Falkland Islands and died at the surface. The crew immediately froze its body and it was sent to be preserved in the museum by the Curator of Molluscs, Jon Ablett. It is called Archie, an affectionate short version of its Latin name Architeuthis dux. It is the longest preserved specimen of a giant squid in the world.

Jon Ablett on Archie the giant squid

"It really has brought science to life for many people," says Ablett. "Sometimes I feel a bit overshadowed by Archie, most of my work is on slugs and snails but unfortunately most people don't want to talk about that!"

And so today we can watch Archie's graceful relative on film and stare Archie herself (she is a female) eye-to-eye in a museum. But have we finally slain the monster of the deep? Now we know there is nothing to be afraid of, can the Kraken finally be laid to rest? Probably not says Classen. "We humans are afraid of the strangest things. They don't need to be realistic. There's no indication that enlightenment and scientific progress has banished the monsters from the shadows of our imaginations. We will continue to be afraid of very strange things, including probably sea monsters."

Indeed we are. The Kraken made a fearsome appearance in the blockbuster series Pirates of the Caribbean. It forced Captain Jack Sparrow to face his demons in a terrifying face-to-face encounter. Pirates needed the monstrous Kraken, nothing else would do. Or, as the German film director Werner Herzog put it, "What would an ocean be without a monster lurking in the dark? It would be like sleep without dreams."

© The Trustees of NHM, London

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published16 June 2015

- Published9 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015