The special water flown in for Princess Charlotte

- Published

When Princess Charlotte is christened on Sunday, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, will baptise her with water from the River Jordan. The same water was also used at the christening of Charlotte's brother, George, two years ago. Why?

Contrary to how it is traditionally represented in songs, poems and paintings, the River Jordan is unimpressively shallow, muddy and narrow.

It is less than 10m (30ft) across and about 2m (6ft) deep.

However, these reed-lined waters overflow with spiritual significance that makes them a precious resource.

The tribes of Israel under Joshua are said to have crossed here to enter the Promised Land after years of wandering in the desert.

This is also where it is believed Jesus was baptised by Saint John, a preacher who wore a cloak of camel hair, lived on locusts and honey, and developed the practice of immersing people in the river to show they had repented of their sins and turned to God for forgiveness.

Nowadays nearly half-a-million annual visitors, mostly Christian pilgrims, flock to rival baptism sites on opposite banks of the river a few miles north of the Dead Sea - one side is in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, the other in Jordan.

Here they pray and sing hymns, and many renew their faith by donning white robes and plunging in.

The far side is Jordan - an area of no-man's-land runs down the centre of the river

"Whatever happens, don't swallow it or let it get up your nose," a Jordanian Catholic woman instructed her relatives a few days ago, as they prepared to be baptised - the water is said to be polluted by sewage and industrial effluent.

A few yards away, on the West Bank side, a young Russian woman emerging from the water showed me three decanters she was stowing away in her handbag "as special gifts".

Kensington Palace would not say how water from the river was obtained for Princess Charlotte's christening, but a Jordanian official told the BBC that it had been sent by his country's royal court.

"We organise the process of bottling holy water from the River Jordan," says Dia Madani, head of Jordan's baptism site commission.

"We provide it to investors after cleaning it, sterilising it and giving it the blessings of religious men. Each bottle has a label from the commission."

There is a similar trade in Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

The Israeli Nature and Parks Authority sells empty plastic containers for tourists to fill with water

Israeli tourist stores offer high-end products from pre-filled, medallion embossed vessels, "recommended for christenings", to water-filled glass crucifixes for $56 (£36).

Similar items can be picked up in duty free shops at the airport and on Amazon and eBay.

"Everyone has a story for why they want it," says Riyad Mitri, a souvenir seller in Bethlehem. "Some say it's to baptise children, some drink it or use it for healing. Others believe its special properties will help their plants grow."

Naming the site

Qasr al-Yahud, from the Arabic "Castle of the Jews" is the official name used by the Israeli authorities for the baptism site they run in the occupied West Bank near Jericho. This is the traditional site where Jesus's baptism is said to have taken place and the most popular spot for pilgrims.

Palestinians traditionally call the same baptism site on their occupied land in the Jordan Valley, al-Maghtas.

The Jordanian baptism site on the East bank of the river is known as Bethany beyond the Jordan. There is a body of recent archaeological evidence that this is the likely site of Jesus's baptism. Last year Pope Francis became the third Pope to visit since 2000.

The water is in such short supply that it sometimes has to be diluted as well as purified.

Palestinian Christians complain it is difficult for them to access the holy river, so their supplies are very limited.

"Once or twice a year, during feast days, the Israelis let us fill up to four 16-litre (four-gallon) tanks," says Fawzi Jaqaman, a Palestinian who puts together sets of rosaries, olive oil, soil and water from the Holy Land.

"It's not enough so we have to mix it with regular water."

Church leaders say the waters of the holy river have a special significance.

"There are layers of symbolism that go back to the origins of Christianity not just historically but also geographically," says Father Jamal Khader, head of Religious Studies at Bethlehem University.

On the other hand, Father Jamal takes a very dim view of the trade in the water.

"The Church is strongly opposed to selling blessings or spiritual objects for a profit," he warns. "We know some people do this but it counts as simony and it is a sin."

What is simony?

Simony is defined as "the act... of buying or selling ecclesiastical preferments, benefices, or emoluments; traffic in sacred things"

The name is taken from Simon Magus (Acts 8:18), who offered to purchase from the Apostles Peter and John the supernatural power of transmitting the Holy Spirit

Simony, in the form of buying holy orders or church offices, was virtually unknown in the first three centuries of the Christian church, but became widespread in Europe in the 9th and 10th centuries

Source: OED, external, Britannica.com, external

Not long ago, the baptism sites in the Jordan Valley were a closed military zone. Even after a peace treaty was signed by Jordan and Israel in 1994, access remained severely restricted for some years.

Minefields remain on the West Bank side, and visitors are warned to stick to a path lined with barbed wire and signs that read "Danger - Mines".

There is scholarly evidence that suggests the exact spot where Jesus was baptised is on Jordan's side of the river, though exactly where is hard to determine, partly because the course of the river has changed over time.

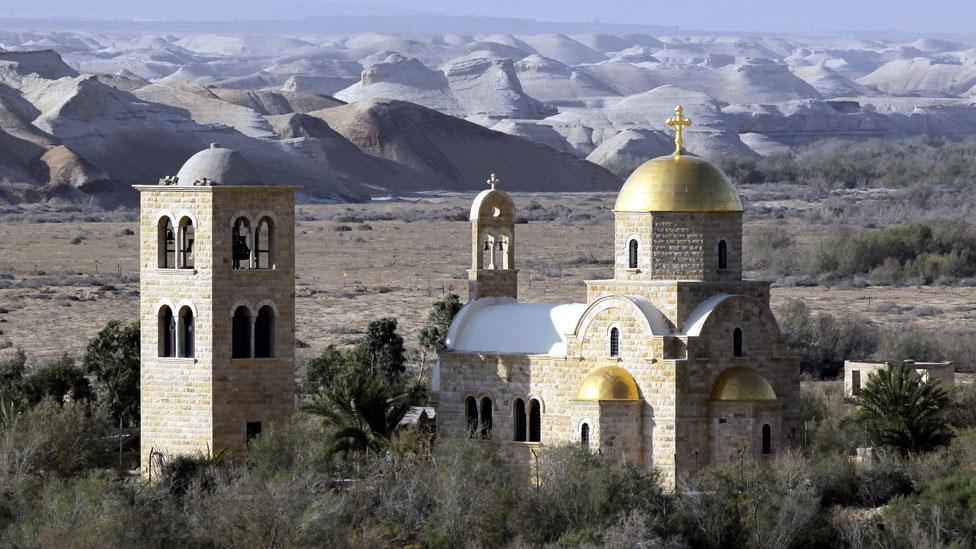

The Greek Orthodox church of St John the Baptist

The Armenian Church of Saint Garabed (right)

Last year, Pope Francis held a mass nearby and the Jordanian authorities are allowing new churches to be built in the area. A new archaeological park has been created around a cave where it is believed that John the Baptist lived.

It all appears to be part of a Jordanian bid to win a bigger slice of the Bible tourism industry, which is worth billions of dollars each year.

At the rival baptism sites, tourists shout to one another across the river. When I was there this week, there were Texans on both sides, a retired Bishop of Durham, and a party of Italians, as well as the Jordanian Catholic family and the Russian tourist.

An Israeli soldier and a Jordanian soldier as well as a Palestinian tour guide took part in the cross-border conversation. Brotherly and sisterly love reigned for a while in the birthplace of Christianity.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.