After being released, US prisoners find new struggles

- Published

"Mass incarceration I would say affects over 60% of the community," Jondhi Harrell says of Nicetown

On Tuesday, President Barack Obama gave a speech in Philadelphia outlining his plans to change the criminal justice system. About five miles north from where he spoke is where you'll find some of the areas hardest hit by the effects of mass incarceration and the lack of opportunities that come with it. Welcome to Nicetown, Philadelphia.

On the day of Obama's speech, J Jondhi Harrell came down from his apartment and walked over to a nearby corner to haul 22-year-old Jeremiah Ross inside the offices of the Center for Returning Citizens (TCRC). Harrell, the executive director of the centre, has been trying to persuade Ross to stop dealing drugs, or "trapping" and instead find a full time job and stable housing.

Harrell tries to entice Ross - a thin, handsome young man with big eyes and a web of tattoos crawling up his neck - with $100 moving jobs, and lets him use the computers in the front office. If he can get Ross to leave the street corner behind, Harrell says, it could be a major coup - Ross is a leader, lots of the neighbourhood kids look up to him.

But Ross recently finished a stint in prison, he has no high school diploma, and right now TCRC can't afford to pay him a living wage. So the streets continue to beckon.

Summer in the City is a season of stories told from today's America about race, identity, policing, inequality, and opportunity. Read more about the project and what people are saying about their city at our Summer in the City page.

What stories should we be telling in your city? Let us know your thoughts at summerinthecity@bbc.co.uk, by using the hashtag #BBCSummerCity on Twitter or texting +18059940222 (that's a US number) .

"After me and my family got evicted, I'm out here," says Ross. "It's hard to find a job, so this all I know. This is the first thing I go to."

Ross says he had no idea the president was making a speech at the Philadelphia Convention Center in a few short hours, or that it was to do with many of the issues that directly impact his life - namely sentencing, incarceration, and the myriad ways that Pennsylvania laws keep former inmates like himself from getting back to life as usual.

"I never really listen to his sermons or nothing," Ross shrugs. "He ain't coming here. He ain't helping me."

Nicetown is about a 15 minute car ride away from Philadelphia's Center City where Obama outlined his plans to reform the criminal justice system at the National Association for Advancement of Colored People's (NAACP) annual convention on Tuesday afternoon.

Obama spoke only a few miles away from Nicetown

This speech came on the heels of his announcement that he is commuting the sentences of 46 nonviolent drug offenders who've been incarcerated in federal prison for many years. While everyone agrees it is an important moment, the word some Philadelphian advocates for the formerly incarcerated use to describe the president is "disappointing."

Obama spoke of an America founded on second chances - but many return to find that Pennsylvania law prevents them from getting licences to do certain types of work, prevents them from getting housing and sometimes bars them from entering their former neighbourhoods altogether. These types of laws are known as "collateral consequences," and according to a national website that tracks them, external, Pennsylvania has nearly 1,000 of these restrictions.

"It's become almost like a sport for the legislators to create all these barriers," says Angus Love, a lawyer with the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project.

Germantown Avenue once teemed with black-owned businesses patronised by neighbourhood residents collecting good wages from nearby factories. Today, nearly half the people living in the 19140 zip code do not have a high school diploma. Most households bring in less than $30,000 (£19,000) a year and the glittering shops have shut down.

A huge number of the estimated 35,000 former inmates who return to Philadelphia each year from federal, state and county lockups head back to North Philadelphia neighbourhoods every year.

Nearly half of the residents of Nicetown don't have a high school diploma

According to 2008 figures, it cost taxpayers $40m to incarcerate men and women from Nicetown - the fifth highest rate in the city.

"In our community, mass incarceration I would say affects over 60% of the community," says Harrell. "You'd be hard pressed to walk down any street in any black neighbourhood in Philadelphia, and knock on 10 doors and find no one who is affected."

It's a neighbourhood that feels the full absence of "missing men," a term used by the New York Times, external to describe the large number of black men ages 25 to 54 who have disappeared from cities around the country due to either early death or incarceration.

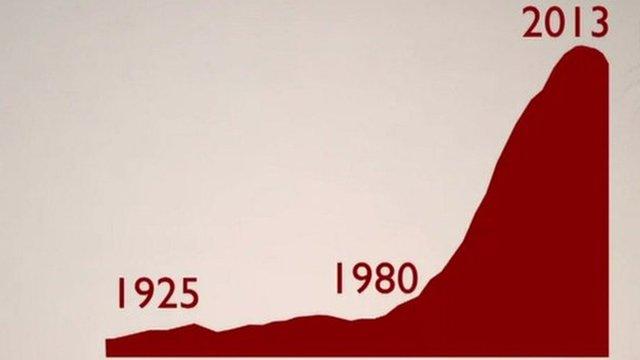

Why are so many Americans behind bars?

Philadelphia is said to be missing 30,000 of these men. Nicetown is exactly the kind of community they're vanishing from.

Once released, these inmates could be said to be joining the ranks of the re-appeared men, and Harrell is one of them.

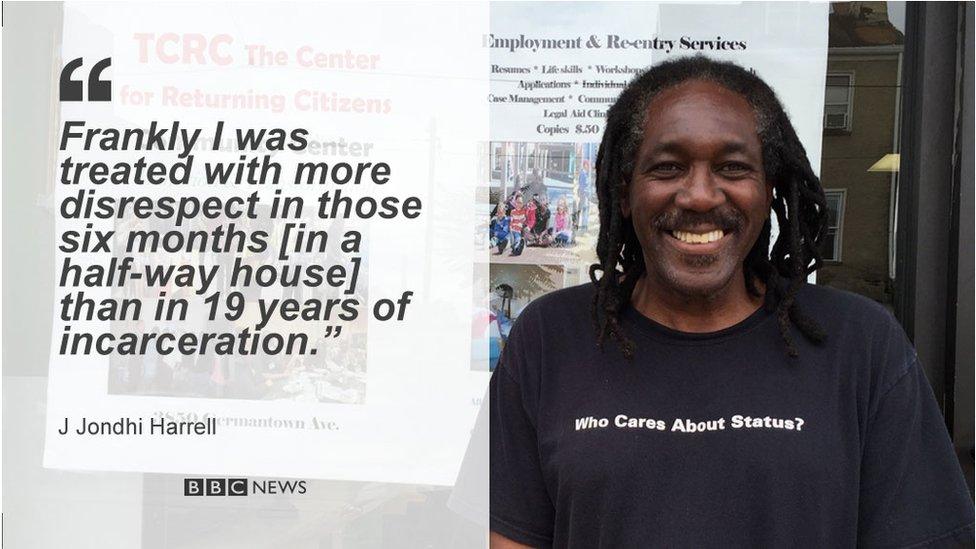

He spent 20 years in federal prison, and returned to Philadelphia five years ago. But don't call him an "ex-con" - he and other activists worked hard to get Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter to issue a proclamation declaring that the city officially refer to former inmates as "returning citizens," and Harrell is deadly serious about changing stigma with language.

He'll never use the word "re-entry" either, a term he associates with the sometimes-exploitative network of halfway houses that are often a required stop after prison.

"Frankly I was treated with more disrespect in those six months than in 19 years of incarceration," he says.

Harrell's three-year-old organisation emphasises a holistic approach for former inmates coming home. Harrell and his staff of four help connect clients to housing and employment, but also encourage the men and women they serve to get involved in community service, to join a faith community if they're religious.

He wants to plant community gardens and start buying up the properties on Germantown Avenue to start business that will employ and train returning inmates - a vision so broad some of his former partners thought he is taking on too much.

"We realise we can't do everything that needs to be done for everybody who comes through our doors," he concedes. "We try to create a family type of culture."

In fact, job placement and spiritual guidance can only take you so far on the streets of Nicetown. When Harrell thinks about the notion of the "missing men" of North Philadelphia, his thoughts go immediately to Cynthia Muse, who lives just around the corner from his office.

On 31 May, Muse's son Abdul Salaam walked out the door of their row house and headed to a celebration for his 36th birthday. Within hours, he was dead - stabbed in the heart in front of his toddler son and girlfriend in the courtyard of a public housing project less than two miles from his mother's home.

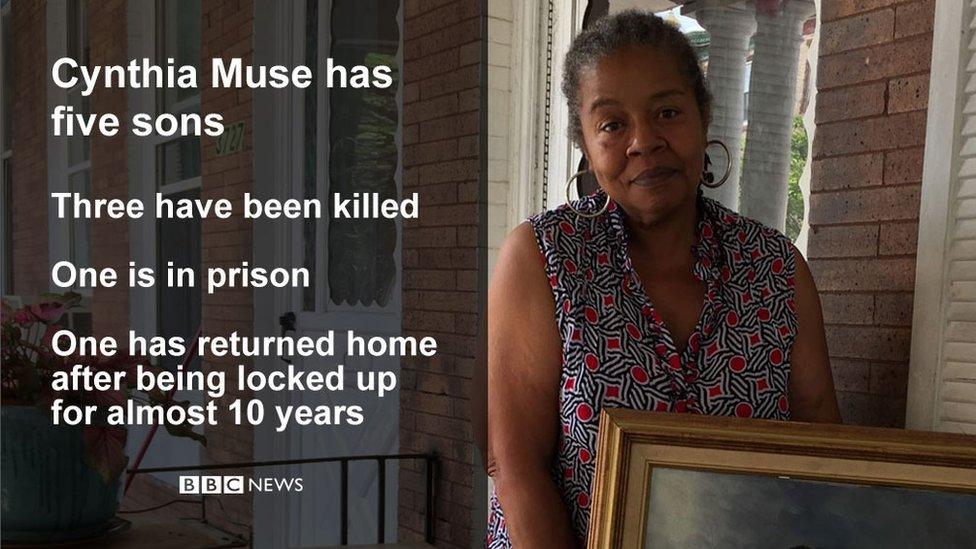

This is not the first time Muse, a mother of five sons, has been through this.

"It was my third time," she says, sitting on her front porch as summer rain taps on her awning. "My emotions and my logical mind is not giving me no answers. Why have you taken a third son from me?"

Muse never seems to get any resolution. Nobody knows how her son Jalaal ended up in the trunk of his own car, or who shot her 26-year-old son Abdul Aliym to death. Her youngest is in prison.

Only one of her sons, Jamal, now has a steady job and a family of his own to look after, despite spending almost 10 years in prison. He's not entirely sure himself how he made it out, but says the deaths of his brothers helped motivate him.

"You have to face yourself," he says. "I don't know what I was angry about. I realised I had to make a change."

- Published30 June 2015

- Published14 July 2015