The pool of blood that changed my life

- Published

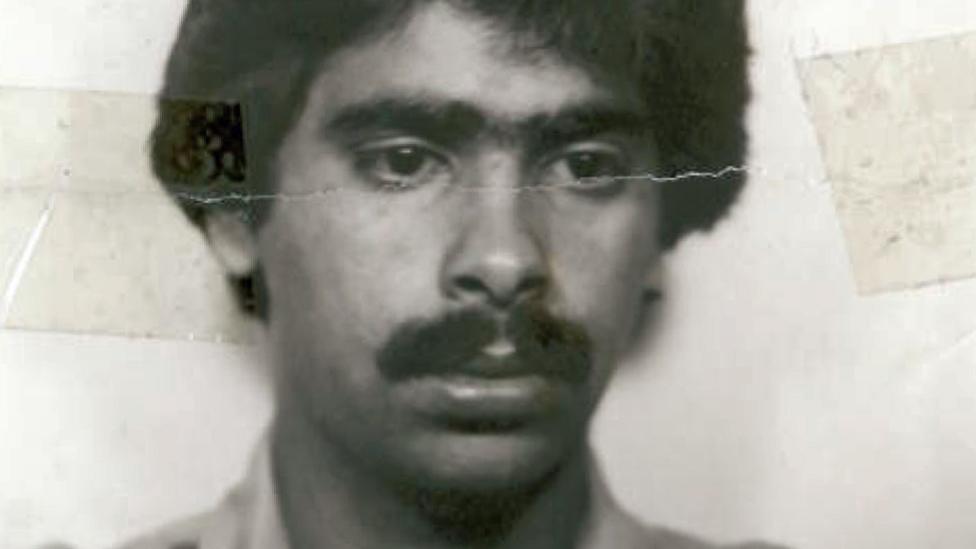

Suresh Grover's family came to the UK from Kenya in 1966 for a better life and a British education. But what he saw and heard growing up in the 1970s changed him. (This article contains language that some readers might find offensive.)

Suresh was a child when he arrived. His father was highly educated and had worked in the civil service. But in Nelson, in Lancashire, the only job available to Asians was factory work, which he did in shifts - day and night.

And there were plenty of moments of overt racism.

"Our woodwork teacher would openly call us wogs. All the kids laughed," says Suresh. He went to the local comprehensive where he was known as Billy.

"Suresh was a foreign name and they didn't want to call me by it."

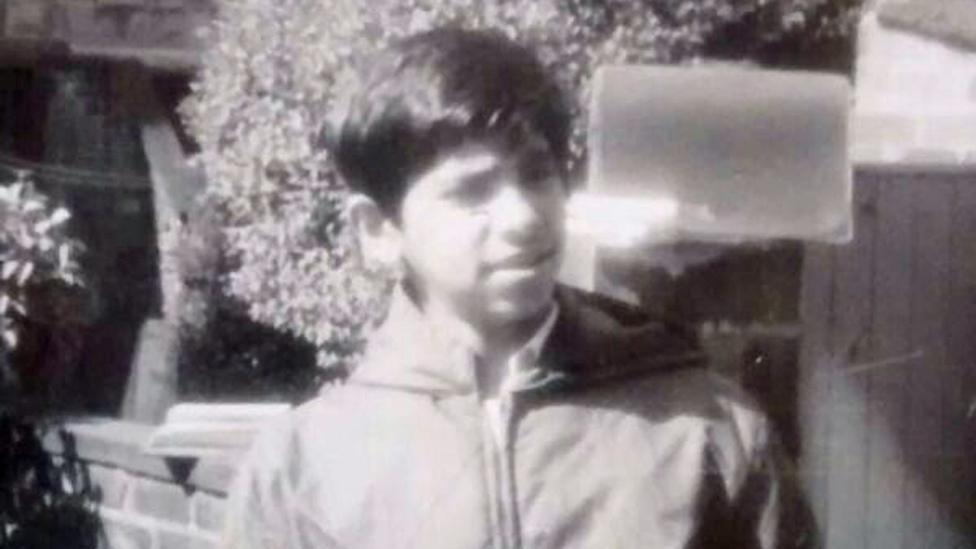

Suresh Grover grew up in Lancashire in the 60s and 70s

Suresh remembers how his schoolmates reminded him of his difference on a daily basis.

"Somebody would pick a fight and everybody would surround you and so you had no option but to defend yourself. Every break time, there'd be a sense of a fight."

And every journey home contained the potential of trouble.

"They knew you'd be passing, you'd be surrounded and again you'd have to fight. My first reaction was to be totally frightened. I would try and argue with them that I am a Hindu and I don't fight because of Mahatma Gandhi."

He lets out a belly laugh as he recalls the scene. "It's ridiculous. They just laughed and smacked me one."

Suresh believes that he never became "anti-white" as there were always small gestures of kindness throughout his childhood.

One act of solidarity sticks out clearly in his mind. Suresh recollects a long period of time when no-one would sit next to him in class.

One day three white girls came up to his desk asking to sit next to him. He was shocked by their action. Then one of them asked if he'd like to go out with her.

"I said why do you want to go out with a Paki? So I reacted in a bad way. I understood her act of kindness but I was too angry to think - do you really want to go out with a Paki? Which is, are you really willing to suffer the consequences?"

He never took her up on her offer. "No I didn't go out with her. I will always remember her and I wish I would meet her again because I want to thank her for it."

When the early pioneers from the Indian subcontinent came over to post-war Britain many remember being met with curiosity. Kulwant Sehli arrived in 1954 with £3 - the maximum amount you could bring from India because of strict currency controls.

Children seeing Kulwant's turban would affectionately call him the Maharaja. He says racist incidents were extremely rare in the 1950s. But by the 1970s they occurred almost every time he left the house.

In the early 1950s there were around 43,000 South Asians in Britain. But by the beginning of the 1970s the numbers had increased to around half a million - because of family reunions and Asians fleeing East Africa. Immigration became a politically charged issue. And around the UK, the National Front were on the rise.

Suresh Grover pinpoints 1973 as a time when things got worse in Nelson, as the skinheads arrived. He recalls vividly his encounter with them one Saturday night when he and his nephew were at the cinema to watch the latest Clint Eastwood movie.

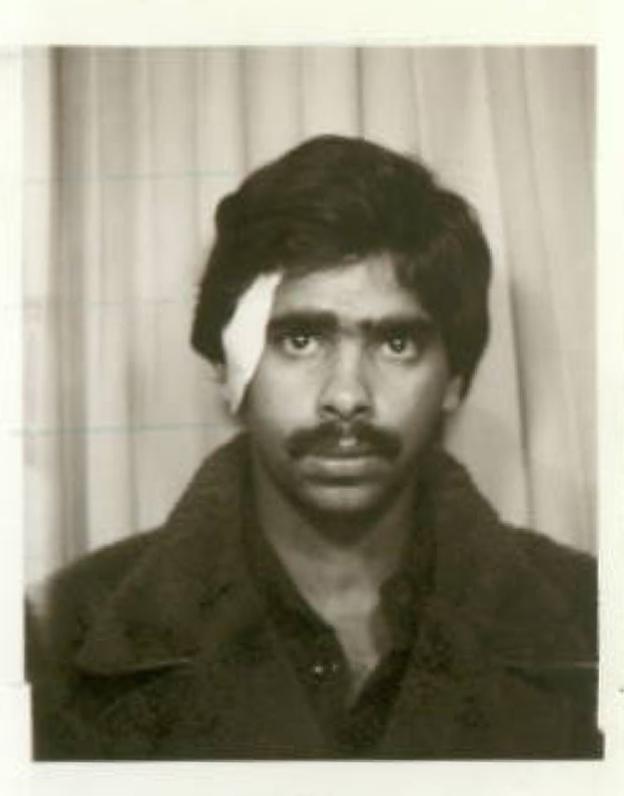

A gang of skinheads came up to the pair, broke his nephew's jaw, and stabbed Suresh. He went to the police station and saw a senior officer. Suresh says no incident report or statement was taken and the policeman never followed up the attack. "I knew I was different and I knew they would not accept me. You realise your lives are very cheap and that burns you inside and it actually hurts you and it makes you angry."

A photo taken shortly after Suresh was attacked

Suresh's father had lived through the violence of partition in 1947 which divided India and saw the birth of Pakistan. His first reaction was that Suresh - a Hindu - must have been stabbed by a Muslim. "My father could never understand why a British person would stab me, he would think it was another Asian person. He believed in British people - he knew that was not true but he had to believe it to survive in a place like Nelson."

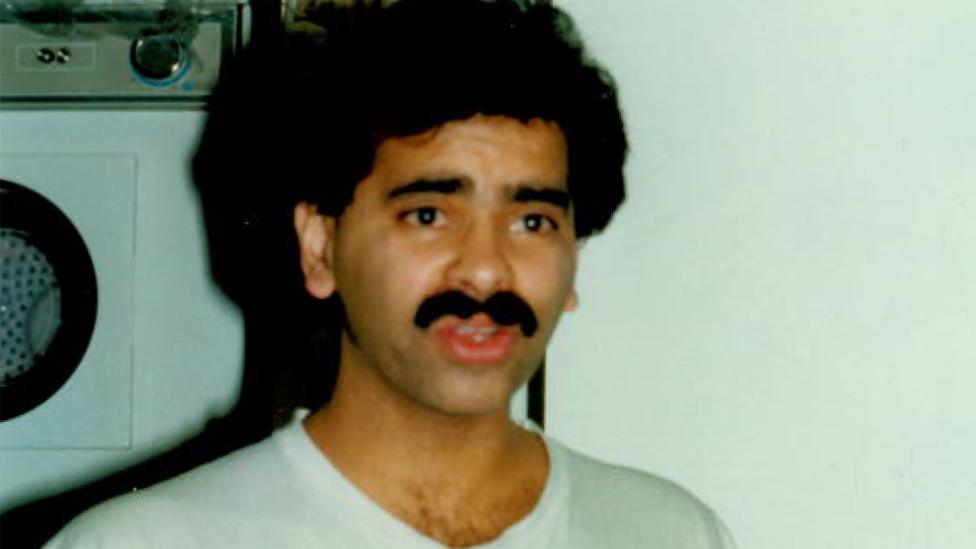

Suresh had enough and left Nelson for good. He went to college for a year in Burnley and then moved to Southall, West London.

He was shocked by the number of Indians there. But then an event occurred which changed his life. His political awakening occurred in a busy part of Southall's High Street.

On 4 June 1976, Suresh, then aged 22, came across a pool of blood on the pavement. He asked a police officer standing by it what had happened and was told someone had died the previous night - he remembers his exact words - it was just an Asian.

Suresh was furious at the policeman's dismissive attitude. He went to get a piece of red cloth to cover the blood. He put bricks around it so no-one would walk on it, as a sign of respect. He erected a makeshift sign saying someone had died.

Suresh didn't even know at that point who it was. But by the evening everyone knew the victim's name. Gurdip Singh Chaggar. The 18-year-old student had been murdered by racists. Suresh and hundreds of his generation took to the streets in protest. The blood on the pavement had still not been cleared.

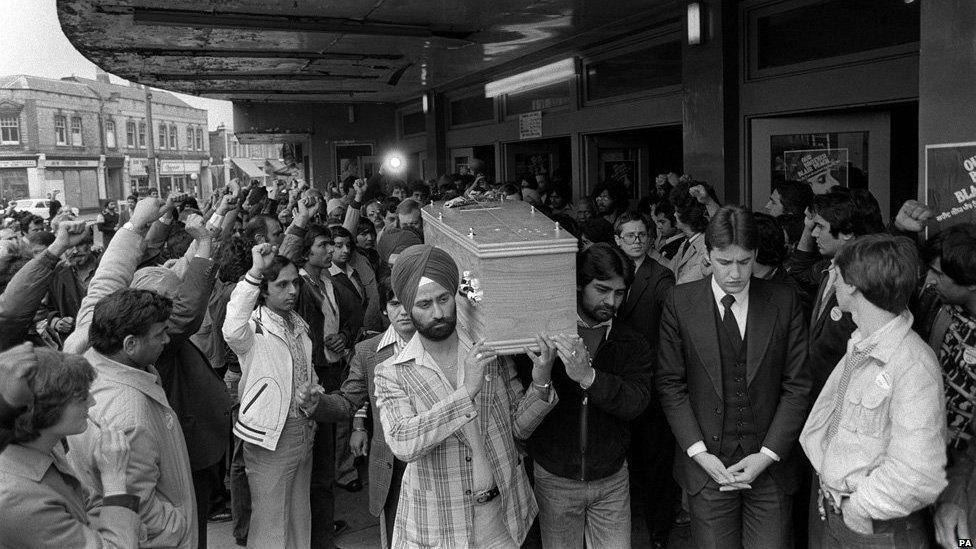

Asian community leaders head a procession through Southall after the stabbing of Gurdip Singh Chaggar, 1976

"It was the first time young people - mainly Asians but with a sprinkling of African-Caribbean people from Southall - took to the streets and organised themselves as a youth movement against racial violence and police harassment in Southall," says Suresh. "The older generation were totally bewildered and fearful of what we were capable of. They were really frightened of what the police would do to us."

Many from the first generation had kept their heads down when confronted with abuse. Gurhurpal Singh, one of the those from the next generation, grew up in Leicester. He was at school and university in the 1970s and is now a professor at SOAS in London.

"I think the first generation were generally not very reactive. They were inclined to be unresponsive to acts of violence and discrimination or take it in their stride. They felt that they were visitors in this country."

When Chaggar died, Kulwant Sehli had been living in England for 22 years, well over half his life. He says his generation had to be "deaf and dumb to racist abuse", but he understood why his children's generation reacted as they did to violence and abuse and fought back. "Why should they be told go home? This is their home."

After Gurdip Singh Chaggar's death Suresh Grover became one of the founding members of the Southall Asian Youth Movement. Similar groups sprung up across the country.

Their slogan was: "Come what may, we are here to stay."

"We were British Asians with black politics and we wanted to unite people to combat the issue of racism," says Suresh. He remembers at that time there were no divisions between the South Asian community. "We realised religion, ethnicity, identity had no role or significance in what we were doing, so those issues didn't come up."

Suresh found himself at the centre of events again three years later when, weeks before the 1979 General Election, the National Front decided to hold a meeting in Southall's town hall.

Thousands - mainly Asians - but also anti-racist supporters took to the streets in protest. Suresh was in the middle of it all.

He witnessed a white priest defending an old woman with an umbrella who had been hit by a policeman with a truncheon. "The priest got charged with threatening behaviour," says Suresh.

But the death of one man, a New Zealand-born teacher - Blair Peach - protesting against the National Front, would become iconic. Gurhurpal Singh was watching these events on television as a university student.

Blair Peach's death

Blair Peach's coffin being carried during his funeral

Clement Blair Peach (1946-1979) was a white New Zealand-born teacher who was killed during an Anti-Nazi League demonstration against the National Front in Southall

Died from injuries to the head, and a jury recorded verdict of death by misadventure; his partner, Celia Stubbs campaigned for many years for public inquiry into his death

In 2010 a Metropolitan Police report, external admitted that one of its officers was probably responsible for Peach's death

He believes the events in Southall following the death of Gurdip Singh Chaggar and Blair Peach were a turning point for South Asian communities across the country.

"The significance of 1976 and 1979 is extremely important because Southall was one area where the Asian community was settled in large numbers and right-wing groups were deliberately intent on provoking a reaction and that reaction came in a very strong way, in response, to the death of Blair Peach and it also drew a red line - we won't take this."

For Suresh these were pivotal events not only for him but also many of his generation. He is now a prominent anti-racism campaigner.

Back in the late 1970s he came to a conclusion which still guides him.

"We are likely to die in this country. We don't have a place we can call home like our elders, which is going back to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh or Sri Lanka. We want to live as equal citizens. So if it means staying and fighting that's what we have to do and we're not going to give an inch to that."

Suresh's and other stories can be heard in Three Pounds In My Pocket (series two) at 11:00 BST on 5, 12, and 19 August on BBC Radio 4.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.