VJ Day: Surviving the horrors of Japan's WW2 camps

- Published

Tens of thousands of British servicemen endured the brutalities of Japan's prisoner of war camps during World War Two. Theirs was a remarkable story of survival and courage, write Clare Makepeace and Meg Parkes.

Looking today at 94-year-old Bob Hucklesby from Dorset, with his hesitant gait yet determined demeanour, it is almost impossible to imagine what his mind and body once endured.

He was one of 50,000 servicemen to experience one of the worst episodes in British military history and will be one of those leading Saturday's VJ day commemorations.

Along with 50 other PoWs, he will attend a service at St Martin-in-the-Fields, in London, and then lay wreaths at the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

Never before, or since, have such large numbers in Britain's Armed Forces been subjected to such extremes of geography, disease and man's inhumanity to man, as were the prisoners of the Japanese in World War Two.

Bob Hucklesby, centre

A quarter died in captivity. The rest returned home sick and damaged.

For three-and-a-half years, they faced unrelentingly lethal conditions.

The average prisoner received less than a cup of filthy rice a day. The amount was so meagre that gross malnutrition led to loss of vision or unrelenting nerve pain.

Diseases were rife. Malaria and dysentery were almost universal.

Dysentery, an infective disease of the large bowel, reduced men to living skeletons. Tropical ulcers were particularly gruesome.

Lt ME Barrett, who worked in the ulcer huts at Chungkai prison camp in Thailand, wrote about them in his diary. "The majority were caused by bamboo scratches incurred when working naked in the jungle… Leg ulcers of over a foot in length and maybe six inches in breadth, with bone exposed and rotting for several inches, were no uncommon sight."

Random beating and torture was meted out at will by sadistic, brutal and unpredictable captors.

Lt Bill Drower, an interpreter at Kanburi Officers' camp in Thailand, dared to challenge his captors over one translation. He was severely beaten and kept in solitary confinement for the final 80 days of the war.

At the time of his rescue, following the Japanese surrender, he was close to death from malnutrition and blackwater fever, a rare but extremely dangerous complication of malaria.

On top of these horrific conditions, the majority of PoWs worked as slave labourers to keep Japan's heavy industry going. They toiled relentlessly on docks, airfields, in coalmines, shipbuilding yards, steel and copper works.

These brutalities are now well-known among the horrors of WW2.

Less is known about the extraordinary spirit of the prisoners of war - a spirit the cruelty of the Japanese signally failed to conquer.

It is a remarkable story of how they overcame appalling adversity during the war - and how, having survived, they had to do so again in peace because they were so haunted by the horrors they had endured.

Capt David Arkush as painted in 1944 by Gunner Ashley George Old at Chungkai camp in Thailand

One crucial means of survival in the camps was to form strong bonds with fellow prisoners - close friendships were a lifeline in Japanese captivity. Having a small group of three to four mates was essential. They shared food and workload, and nursed each other when sick.

RAF aircraftsman Derek Fogarty, captured in Java, recalled in a 2008 interview: "You bonded like a brother. If a person was sick you took them water, you did their washing. We were so close and it got closer and closer over the years, people would die for their mates, that's how close things got."

Without these mates, many more prisoners would have died.

Dental officer Capt David Arkush remembered in a 2007 interview how "everybody had dysentery. They lay in their own excreta. Unless they had a mucker, a pal, to look after them they stood little chance of survival."

Private Gordon Vaughan

Across individual camps, PoWs pooled their skills and trades to help one another.

Doctors, denied tools or medicine, needed the expertise of others. Medical orderly and former plumber Fred Margarson ran secret PoW workshops at Chungkai hospital camp in Thailand where he supervised the making of artificial legs for tropical ulcer patients.

His friend Gordon Vaughan, a Post Office engineer before the war, made vital medical instruments for examining dysentery patients from old tin cans, and surgical forceps from pairs of scissors.

In even the most miserable conditions, men supported each other through humour. Jack Chalker, a bombardier captured at Singapore, remembered the skeletal patients in a dysentery hut on the Thai-Burma railway.

They ran a lottery as to "who would be sitting on the only bucket in the hut when it finally collapsed". "Such things" he recalled "provided a great deal of laughter".

As many as a quarter of the prisoners died, but 37,500 British servicemen who had initially been taken into captivity lived to see VJ day.

Many thousands of them had to wait up to five weeks, or longer, before the camps they were in could even be found by the Allies. Almost all of them sailed the 8-10,000 miles back to Britain, disembarking in either Liverpool or Southampton, more than five months after the war in Europe had ended.

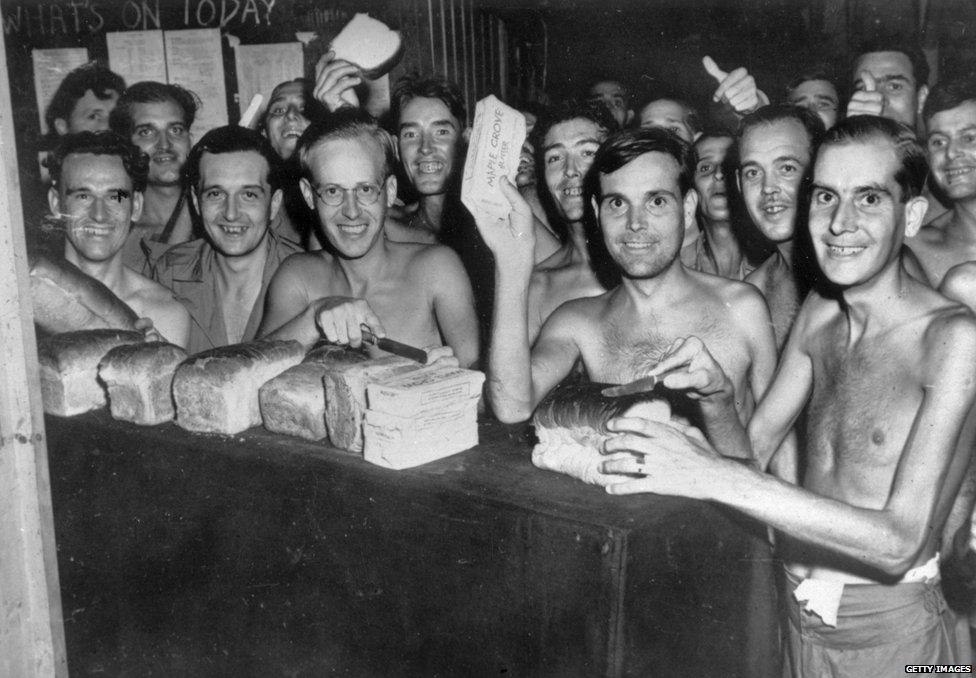

Allied prisoners of war at Aomori in Japan cheer as approaching US Navy brings food in 1945

The main victory celebrations had faded long ago for most Britons. They were now preoccupied with post-war problems of finding work and feeding their families.

Rather than feeling jubilation, these returning ex-PoWs were full of shame and guilt at having surrendered, and having survived. These feelings of guilt were compounded by a difficulty in telling people about what they had been through.

Jack Chalker experienced a physical block when he tried to answer a question during an interview in 2010. "The words just wouldn't come out. I couldn't speak, not a sound would come. It was very frightening. I felt such a fool and I didn't want it to happen again so I decided not to speak about it."

Many turned to each other for support, just as they had done in captivity.

Soon, PoW clubs sprang up in village halls and pubs across the country.

These clubs provided a place where former prisoners could meet regularly and where the trials and the friendships of prisoner-of-war life were understood.

Barbara Wearne, whose husband was captured at the fall of Singapore and died in 1966, leaving her with four young children, attended some of the PoW meetings in Plymouth.

She observed the conversations between these men. She recalled, in an interview in 2007: "They were back again as they had been in prisoner camp, and they were buddies again. They could talk and understand each other. I think that that's one of things they must have missed terribly when they came back, to lose that fellowship."

The gatherings also saw some bizarre activities.

The London Far East Prisoner of War Social Club held its first "Tenko" night in 1948.

Tenko was the Japanese command for roll call, an order made familiar to the British public through the 1980s TV drama series. Every day in captivity started with the same routine. Prisoners were woken between 5am and 6am, and lined up for a tedious process of being counted and recounted.

PoWs spent these Tenko nights comparing notes about their time in captivity. Then, at 10pm, the command was cried out, and two Japanese officers and two Korean guards appeared.

They were British ex-PoWs dressed in enemies' uniforms, souvenirs from their time in captivity. Hundreds of PoWs jumped to obey the order, and then paraded round the floor in a parody of the grim, daily processions.

These performances were not just confined to the Tenko nights.

The London Far East Prisoner of War Social Club also organised annual reunions. The venues, first the Royal Albert Hall and then Royal Festival Hall, were always brimming.

The Far East PoW sketch was often the hit of these evenings.

Just as at the Tenko nights, ex-prisoners took on the role of their Japanese guards. Others played themselves from those dark days. The guards slapped and bashed the prisoners.

In photos of these sketches, there is no hint that PoWs found the plays disturbing. The actors are beaming. Those who took the role of the guards appear to revel in the chance to mock their captors, through their greatly exaggerated po-faced expressions.

In 1956, Bryn Roberts commented: "It gives great pleasure to us and to them [the actors] to be able to laugh at some of the things that were not so entertaining when we were prisoners."

These sketches probably had a therapeutic value. They have similarities with a form of therapy called psychodrama, now widely practised across the globe, and used for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Imagining the harrowing events they had endured in a safe environment, and expressing previously forbidden emotions, may have helped PoWs deal with their trauma.

Former PoWs, pictured in 2014 - Bob Hucklesby is in the middle row, second from the right

The bonds of friendship found at these annual reunions were unique. They were deep, lifelong and enriching. Through the reunions many men found something positive had emerged out of such horrific times.

Senior officers used their local business and professional connections to help men less fortunate find work.

Many suffered intermittent bouts of fever or chronic diarrhoea, the consequence of malaria and dysentery. As early as 1946, and for subsequent decades, at first dozens, then hundreds, and eventually thousands of men with persistent tropical infections sought medical attention.

Members of local clubs took care of their disabled and afflicted, as well as the widows and families of those who had died. When the London Social Club was first started in 1947, members paid five shillings a year into a fund to help any ex-prisoner known to be in hospital or undergoing economic hardship.

Soon PoWs ensured they received financial support on a much greater scale.

Shortly after the war, local clubs started calling for compensation for how the Japanese had treated these men. Miners from the Rhondda Valley, who had been put to work on the Thai-Burma railway, wanted a share of the £1,250,000 proceeds that Thailand had paid for it after the war.

Ex-PoWs in Lancashire and Cheshire, inspired by a provision made for ex-prisoners in the United States, called for a dollar for each day of their imprisonment.

This was the beginnings of the POWs breaking their silence.

In 1950, these men united to demand, in a loud and confident voice, that compensation be paid to them by the Japanese. This compensation, they insisted, should be one of the terms of the peace treaty with Japan, which was at the time being negotiated and which would formally end World War Two.

The claim was about far more than just money.

It was about informing the rest of the world what Far East PoWs had been through. The "humiliation, the semi-starvation, the cruelty of enforced labour, the many atrocities, and the shocking disease" these men had suffered.

It was about making sure nothing similar ever happened again. "Only in this way," one piece of their campaigning literature emphasised, "will the ex-enemy government realise they cannout get away with such things."

PoWs took their case to the local and national press. Newspapers carried supportive headlines, such as "Justice for Victims of Far East Terror" and "Compensation for Atrocities Urged".

PoWs lobbied Parliament. For two-and-a-half hours the House of Commons debated the issue, and then voted in favour.

In the 1950s, each and every Far East PoW, or the next-of-kin of those who had died, received the equivalent of approximately £1,500 in today's money.

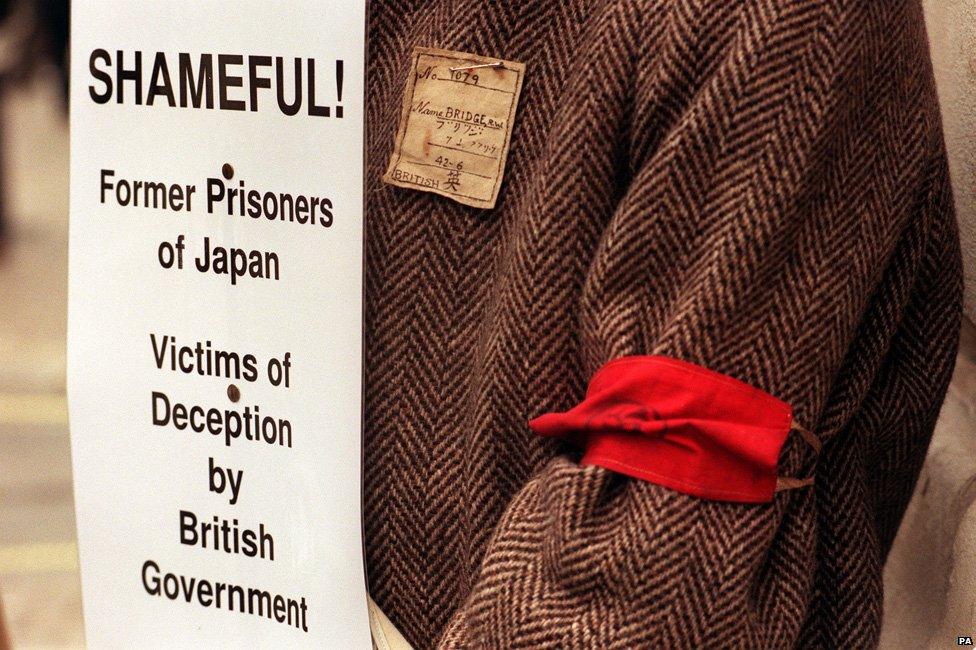

A former PoW demonstrates at the Foreign Office in London in 1999

Over 40 years later, in 2000, the Far East PoWs won another campaign. Surviving Britons who had been held captive by the Japanese, or their widows, would receive a one-off payment of £10,000 each.

In total, almost half of all British Far East PoWs became part of a club or association at some point in their lifetime. This is an extremely high number.

As a comparison, no more than one-tenth of the five million veterans who went through the slaughter of World War One went on to join the British Legion.

Bob Hucklesby is one of the longest-standing members of Far East PoW organisations, having been involved for the past 65 years.

Today, our attention will be concentrated on him and the few surviving Far East PoWs.

These men inspire awe. They are the last remaining tangible link to that horrific episode over 70 years ago, and to the spirit that helped them to survive.

For Hucklesby, the focus of the 70th anniversary VJ day commemorations should not be on him, or his fellow survivors, but on those they left behind.

Seventy years after their cruel deaths, he remembers them more than ever. Today, he wants us to think of them, of the "many young men in their prime who never came home, and who suffered terrible conditions before they died".

More from the Magazine

The fall of Singapore provoked a need for Japanese-speaking British servicemen

It's 70 years since Japan surrendered and World War Two ended. But when war with Japan first broke out at the end of 1941 Britain had been woefully unprepared - not least because almost no-one in Britain could speak Japanese.

How the UK found Japanese speakers in a hurry in World War Two

Dr Clare Makepeace is a cultural historian of warfare, external and teaching fellow at UCL.

Meg Parkes, honorary research fellow, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, is co-author of Captive Memories (Palatine Books, 2015).

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.