What happens to information you give to charities?

- Published

The spotlight is on how charities handle information they gather after an 87-year-old had his details sold on. But what is supposed to happen?

There are several ways that charities and companies ask the public to agree whether to let them share information. The main ones are "opt-in" and "opt-out" boxes.

The opt-in involves leaving a tick to say you do want to receive communications and/or whether you're happy for the charity to share your details with other organisations.

A model of good practice, according to the Information Commissioner's Office, the watchdog that supervises use of data, would be an option like this: "Tick if you would like to receive information about our products and any special offers by post/by email/by telephone/by text message/by recorded call." This, it says, is quite clear.

On the other hand, the opt-out means ticking boxes to say you don't want your information to be shared. This is more common than the opt-in, according to Oliver Smith, a consultant intellectual property solicitor at Keystone Law. "People tend to just go with what's there on the paper," he says.

In 1994, Samuel Rae, then in his sixties, filled in a lifestyle form in a newspaper, the Daily Mail reported, but apparently did not opt out of receiving third-party communication. It seems his details were subsequently sold to two animal charities, the PDSA and the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

Mr Rae became a PDSA donor, but the organisation 10 times passed his details, external on to other organisations, including charities, companies and a listings broker - whose role is to sell details to firms and others who might be interested in them, based on their data. Mr Rae's information ended up being passed on up to 200 times further down the chain.

In 2004, Mr Rae asked the PDSA not to share his details any more. The charity says it "complied immediately with his wishes". "Any data sharing in which PDSA engaged in the past was done in good faith, working with recognised agencies," it adds, saying: "Over two years ago, we proactively decided to stop trading or swapping supporters' personal details."

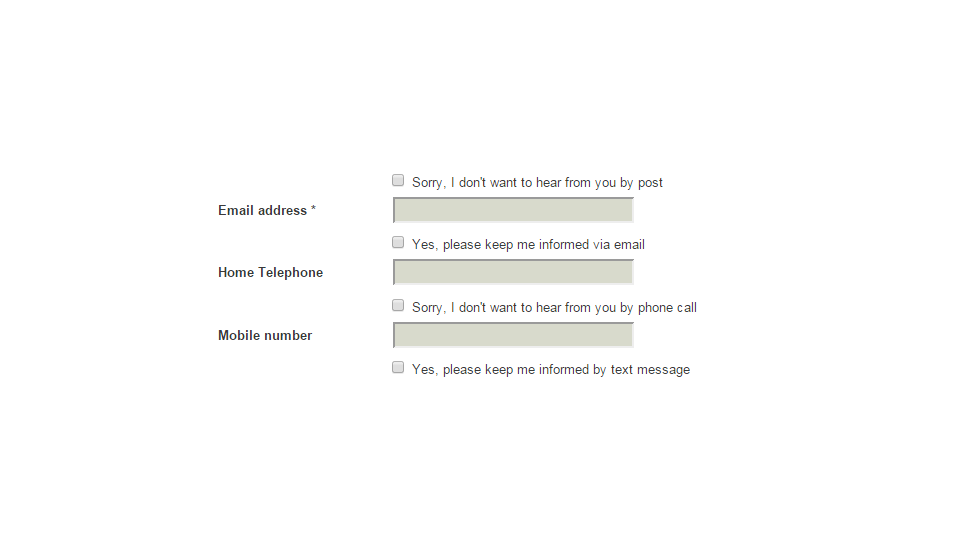

On some forms, charities don't just use one type of box, but alternate between opt-ins and opt-outs within a single section, creating a potentially confusing situation.

Example of consent questions on a charity site

There is an ongoing debate about whether failing to tick an opt-out box, as is thought to have happened with Mr Rae, means someone is actually agreeing to have their details shared. The Data Protection Act,, external passed in 1998 - four years after he filled in the PDSA form - has many "very grey" areas, says Smith.

The European Data Protection Directive, on which the act is based, defines consent as "any freely given specific and informed indication of his wishes by which the data subject signifies his agreement to personal data relating to him being processed".

Hiding a tick-box in the small detail of a form - perhaps in a separate section - might contravene this. "Years and years ago that sort of thing was quite common," says John Mitchison, from the Direct Marketing Association. "The industry has moved away from that. Now, the guidance says that in order to receive marketing you have to have made some sort of positive action so that might be ticking a box on a form, ticking to click online or pressing a button."

Charities have to be able to prove that they have used personal details "fairly and lawfully". In practice, this also means that the use of someone's details should not be used for a purpose that someone would not reasonably expect.

For example, a charity does not need to list all of the companies that someone's details will be sent to. But according to the guidance, external, they should only pass the information on to "reasonably similar" organisations.

"We do not sell any data that we collect to any other organisation," says Jon Bodenham, director of fundraising at Alzheimer's Society. "We believe that other charities should only do so if they have explicit consent.

"We would only want to collect data that helps us understand who a supporter is, their relationship to our cause and enough information so that we can contact them with relevant and timely offers for their support or participation in volunteering, campaigning or fundraising."

Another concern is the length of time over which charities can share the details with third parties, like other charities, companies and list brokers. The Data Protection Act doesn't give an exact limit, but the Information Commissioner's Office recommends not doing so more than six months after permission has been given.

"There is a limit to this," says Mitchison. "You can't have that person hanging around in a pool of data for 10 years and then start selling it to people. That would be unacceptable."

Data protection expert Rowenna Fielding, who used to work in the charity sector, says the organisations, often under severe financial pressure, have not hired enough experts to allow them to avoid legal pitfalls. They have sometimes been misled by list brokers and marketing experts into passing on details, she adds.

At the same time, data protection rules applying to charities are stricter than those for companies, meaning they are more likely to break them. "The charities have used these tactics not because they are evil or venal," says Fielding, "but because they work."

More from the Magazine

The death of 92-year-old poppy seller Olive Cooke focused attention on the way charities raise funds - and in particular on the pleas for donations that arrive via direct mail. What exactly are the techniques used by charities?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.