Ahmed's clock: Just what is a 'suspicious' object?

- Published

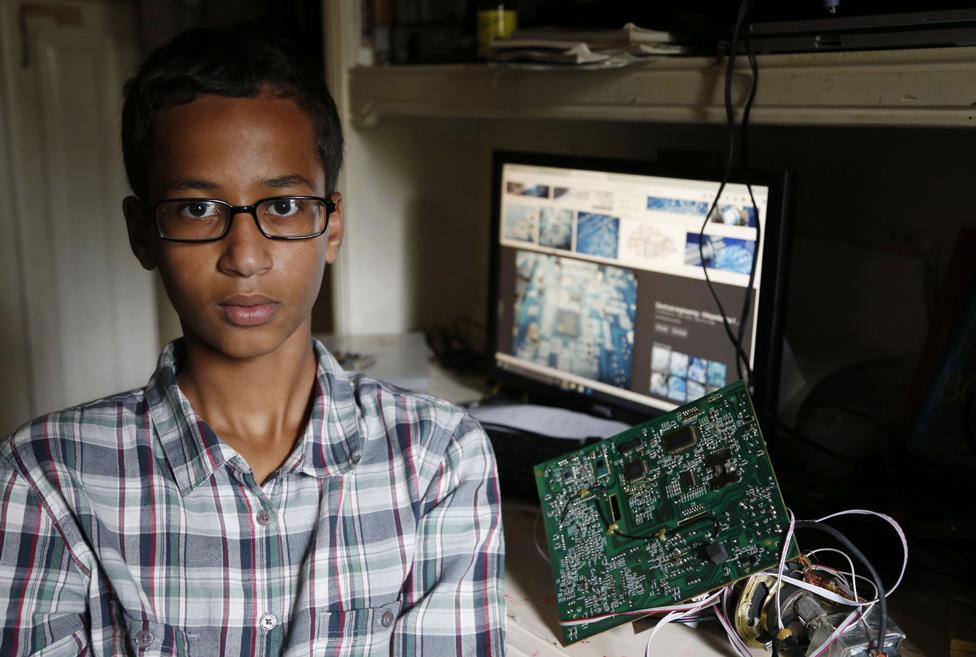

The home-made clock created by Ahmed Mohamed

A 14-year-old boy was arrested in Texas after a teacher mistook his home-made clock for a bomb. But when is it reasonable to regard an object as "suspicious"?

Pictures of Ahmed Mohamed being placed in handcuffs have caused outrage. In response, the school said in a statement that it would "always ask our students and staff to immediately report if they observe any suspicious items".

We hear exhortations like this every day. For instance, travel on a train in the UK and you hear the same message at every stop: "Please do not leave items unattended on the railway and beware of any suspicious items or behaviour. Report these to a member of staff or police."

Ahmed Mohamed at home

In an era of increased terrorist threat, the public keeping their eyes open for potential bombs is vital. But what sort of items count as "suspicious"?

One of the problems is that few people will have actually seen an explosive device in real life. Ahmed's clock consisted of a circuit board and power supply connected to a digital display by a few wires. "It looks like a movie bomb to me," said one of his questioners. But social media was ablaze with people ridiculing that judgement.

But as Ahmed Mohamed's case shows, it's easy to get things wrong.

Our biases, implicit or otherwise, can also play a leading role. Ahmed's father has suggested that his son was mistreated because he is a Muslim. Accusations of "profiling" are frequently brought up in terrorism scares.

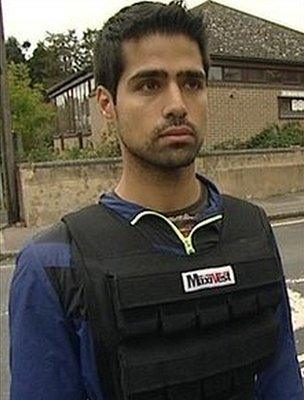

Goudarz Karimi's weighted vest was mistaken for an explosive device

In 2011, an Iranian student from Oxford University wore a weighted vest as part of an exercise regime. He was soon surrounded by an armed response unit who mistook him for a suicide bomber. Police said that it was an appropriate response and that the decision was not made on ethnicity alone.

A passenger in Edinburgh Airport found himself surrounded by police, external in 2012, after his bottle of Spicebomb aftershave was mistaken for a hand grenade.

In August this year a PR stunt caused the evacuation of the Science Museum in London. A van parked outside with "Iran is Great" painted on the side was mistaken as a bomb threat. Later, it was discovered that the vehicle belonged to a family who were travelling across Europe in a small campaign to try and change people's views of Iran.

In 2007, large areas of Boston in the US were shut down, external after passers-by spotted a series of suspicious objects around the city. Strange black boards with wires sticking out of them turned out to be light-up cartoon characters that were part of an advertising campaign.

Nobody wants to mistake an innocent person for a terrorist. Getting it wrong can also be extremely embarrassing, even for the experts.

For those who are perceived to have overreacted to a threat there can be criticism. Ahmed Mohamed is already a cause celebre. Mark Zuckerberg has invited him to come to Facebook's HQ. President Barack Obama has invited him to the White House.

And there's been plenty of criticism online. One tweeter suggested, external: "Students deserve teachers who can tell the difference between a clock and a bomb." For many, a child like Ahmed, wearing a Nasa T-shirt, and with a proclivity for being a maker, would surely weigh on the side of an innocent explanation.

But the school and local mayor have said procedures were followed correctly. For some the danger of missing a real bomb means the threshold for suspicion should always be low.

And when making a decision about whether to report an object, people will often assess whether something looks "classically dangerous", explains Sandi Mann, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Central Lancashire. "I think we expect incendiary devices to be ticking and to have wires sticking out. Unfortunately, nowadays we are probably alert to the wrong things."

Despite this, people are routinely urged to report suspicious items to the police. The phrase "Unattended baggage will be removed and may be destroyed," will be familiar to everyone who has ever boarded an aeroplane.

But when exactly a lonely suitcase becomes a potential bomb threat is not clear. Air security officials will not explain their methods for deciding when an object is worth investigating in case the information helps terrorists avoid detection or inspires practical jokers.

Without an official guide, most people have to rely on their individual instincts. "It's down to perception," says Simon Bennett, director of the Civil Safety and Security Unit at the University of Leicester. "Somebody could consider an empty fag packet to be suspicious."

In fact, empty cigarette packets would probably actually have caused trouble in the 1980s, he adds. There was a period when some animal rights activists were putting small incendiary devices hidden as cigarette packets in pockets of fur coats.

In many cases, the context of an object often ends up being more important than the item itself. People might assume that a rucksack on a train has an owner but might be more suspicious of an oddly-shaped box that seems to be on its own.

"We're really looking out for something that hasn't got an owner," Mann adds. "The next level would be something that looks out of place."

Recent events will also play a role. After the 7/7 bombings in London people were asked to be more alert to bomb threats on the capital's underground network. Ten years later, the attack is still likely to be affecting people's behaviour.

"I'm pretty sure that if a backpack was left unattended on a Tube carriage that somebody would at some point draw the attention of the staff to that backpack," argues Bennett.

Our default behaviour is often to do nothing about suspicious objects, says Mann, partly because people do not want to make a fool of themselves. "It's not our norm to take suspicious packages seriously."

"Diffusion of responsibility" also plays a role, she adds. In a classic psychology study researchers put people in a room and filled it with smoke to see what they would do. People who were on their own were more likely to take action, external than those who were with other people.

"We rely on other people to tell us how to act in times when we are uncertain," says Mann. This could affect whether or not we report an unattended bag in a crowded train.

We can't know how good the general public is at spotting a genuine danger. Bennett says that it's not possible to measure how vigilant people are because we do not know how many suspicious packages go unreported.

In the end, we all think we know when someone has overreacted, but it remains difficult to set an objective standard for suspicion.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.